Peer support is more than the employment of people with lived experience in paid support roles; it is the employment of people who share some of the experiences of people using services (peers) specifically to draw on these shared experiences and ways they have found to live well (their experiential knowledge) – to provide support based on shared understandings, mutual problem solving, a belief in the possibility of recovery, and time together to find hope, solutions and connections.

17 ImROC Preparing Organisations PSW Briefing Paper outlines how organisations can enable PSWs to work to their full potential, to give careful consideration to the role: why are they PSWs? Who are they seeking to employ and how will recruitment and selection ensure that this is achieved? What is the role of PSWs? Where are they going to be employed to enable them to fulfil this role? How will they be supported, supervised and developed within the organisation? What structures are needed to enable them to have a collective voice so that they can influence improvements in the quality and effectiveness of services?

This guidance draws on research and guidance papers as well as the experience of PSWs and employers from NHS, Local Authority, third sector and voluntary sector organisations. It begins with the reasons why organisations might employ PSWs and why organisational preparation is so important, and goes on to provide guidance for organisations including: managers, team members/colleagues, Human Resources and Occupational Health, Learning and Development provision (for all staff), peer

supervision and support.

ImROC offers a range of peer support training and consultancy. We support organisations to employ peers within their workforce and train Peer Support Workers for their new role.

17. Preparing Organisations for Peer Support: Creating a Culture and Context in which peer support workers thrive

Julie Repper, Liz Walker, Syena Skinner, Mel Ball

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Heath Education England (HEE) for funding the coproduction and writing of this paper. ImROC has previously written on this subject in our earlier Briefing Papers: Briefing Paper 5 Peer Support Workers Theory and Practice and Briefing Paper 7 Peer Support Workers: A Practical Guide to Implementation

1. INTRODUCTION

This paper provides information and guidance for organisations that employ, or are considering employing, peer support workers (PSWs). Peer support is a new role within many mental health services. It is not merely the employment of people with lived experience in paid support roles; it is the employment of people who share some of the experiences of people using services (peers) specifically to draw on these shared experiences and ways they have found to live well (their experiential knowledge) – to provide support based on shared understandings, mutual problem solving, a belief in the possibility of recovery, and time together to find hope, solutions and connections.

If organisations are to enable PSWs to work to their full potential, they need to give careful consideration to the role: why are they employing PSWs? Who are they seeking to employ and how will recruitment and selection ensure that this is achieved? What is the role of PSWs? Where are they going to be employed to enable them to fulfil this role? How will they be supported, supervised and developed within the organisation? What structures are needed to enable them to have a collective voice so that they can influence improvements in the quality and effectiveness of services?

This guidance draws on research and guidance papers as well as the experience of PSWs and employers from NHS, Local Authority, third sector and voluntary sector organisations. It begins with the reasons why organisations might employ PSWs and why organisational preparation is so important, and goes on to provide guidance for organisations including: managers, team members/colleagues, Human Resources and Occupational Health, Learning and Development provision (for all staff), peer supervision and support.

2. Why employ peer support workers?

There is increasing evidence that, where peer support workers are employed in a supportive environment with appropriate supervision and support, they contribute to improvements in the experience and outcomes of the people they support; they report benefits for their own recovery, and they can help to drive forwards a more recovery focused culture.

2.1 Benefits for people supported by peer support workers

In a recent review of the evidence about Recovery, Slade and his colleagues concluded that there is “substantially more randomised controlled trial evidence supporting the value of peer support workers than exists for any other mental health professional group, or service model”1. They summarised this research evidence as follows:

In no study has the employment of peer support workers been found to result in worse health outcomes compared with those not receiving the service. Most commonly the inclusion of peers in the workforce produces the same or better results across a range of outcomes.

The inclusion of peer support workers tends to produce specific improvements in service users’ feelings of empowerment, self-esteem and confidence. This is usually associated with increased service satisfaction.

In both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, patients receiving peer support have shown improvements in community integration and social functioning. In some studies, they also bring about improvements in self-reported quality of life measures, although here the findings are mixed.

When patients are in frequent contact with peer support workers, their stability in employment, education and training has also been shown to increase.

NESTA and National Voices2 undertook a meta-analysis of a much broader range of over 1000 peer support studies and found that peer support is a term that includes many different approaches, contexts, components and beneficiaries. Nevertheless, the overall picture is one of benefit. They found that peer support:

- has the potential to improve experience, psycho-social outcomes, behaviour, health outcomes and service use among people with long-term physical and mental health conditions

- can improve experience and emotional aspects for carers, people from certain age and ethnic groups and those at risk, though the impact on health outcomes and service use is unclear for these groups

- is most effective for improving health outcomes when facilitated by trained peers

- is most effective for improving health outcomes when delivered one-to-one or in groups of more than 10 people

- works well when delivered face-to-face, by telephone or online

- is most effective for improving health outcomes when it is based around specific activities (such as exercise or choirs) and focus on education, social support and physical support

- works well in a range of venues, including people’s own homes, community venues, hospitals and health services in the community.

2.2 Benefits for peer support workers

While these findings indicate clear benefits for people who receive peer support, there is also evidence that peer support can benefit the peer support workers themselves. It brings all of the benefits of employment (pay, structure, social contact, self esteem), for some it is helpful to be able to ‘give back’ to services that have helped them or to contribute to the improvement of services; for others it is helpful to be able to contribute to others’ recovery, and for many becoming a PSW allows them to turn an often difficult experience into positive skills.

2.3 Benefits for Organisational Culture

At an organisational level, PSWs can drive forward a change in culture. They bring a different perspective into the workforce, they have not been trained or socialised into traditional practices, rituals, routines and beliefs but operate from their own experience.

This is invaluable in delivering services that are acceptable, accessible and effective for people using services: PSWs have been in this situation, they know what it feels like and given support, encouragement and appreciation of their perspective, they can contribute to the development of more sensitive, person centred and recovery focused practices, language, documentation and relationships.

Finally, the inclusion of peer workers in the workforce can be a powerful way of the addressing negative staff attitudes that still exist in places3. The most effective approaches to reducing stigma are those that include direct contact to allow both groups to identify and share their common humanity. Employing peer workers has been shown to work in this way, contributing towards more positive attitudes with higher expectations and greater hope for Recovery among staff4. Thus, peer workers can contribute towards creating an organisational culture that is more recovery focused.

3. Why Prepare the Organisation?

3.1 Creating a safe environment for PSWs

There are many reasons why organisational preparation for PSWs is essential. Of primary importance is the emotional and physical of safety of the peer workers themselves and the people with whom they work.

PSWs, by definition, draw on their own experience to support others. In order to do this, they are open about aspects of their life in ways that other staff rarely are. This places them in a vulnerable, potentially stigmatising position. Athough attitudes towards people with mental health problems have improved over the past decade5 too often assumptions are made about peer support workers based on ill-informed and negative beliefs about people who experience mental health conditions.

Research demonstrates that within the workplace context, people with mental health problems are perceived as less competent, dangerous, and unpredictable and that work itself is not good for these people6 and this is mirrored among healthcare providers who tend to hold pessimistic views about the reality and likelihood of recovery7,8.

This is particularly the case among those professional staff working on inpatient settings who rarely see people who use services other than when they are at their most distressed9. It is in these teams that attitudes show most improvement once peer workers are employed10, perhaps not surprising given working alongside PSWs gives them the positive contact that is known to improve attitudes. However, the potential for discrimination and the evidence that many existing staff with mental health problems do not disclose their condition for fear of repercussions clearly demonstrates the need for careful preparation before employing PSWs11.

Organisational preparation needs to ensure that all staff are aware of why PSWs are being employed, how they will be recruited and prepared, what employment conditions and sickness absence arrangements are for PSWs.

3.2 Gaining shared understanding of the meaning and purpose of peer support

Organisational understanding of peer support must go beyond practical considerations to recognise political and philosophical debates about what peer support means, how decisions about what PSWs do are integral to their identity, effectiveness and ‘fit’ in the organisation, and how the introduction of PSWs is not merely the introduction of a new role in the workforce.

Rather, it heralds new discussions and developments in organisational culture and practices. Peer support is underpinned by principles such as mutuality, equality, freedom, safety…. which cannot be implemented in settings where PSWs are expected to implement coercive, compliance-focused and restrictive practices.

This places PSWs in an impossible ethical predicament “either follow the organisational line and fail your own heart, or leave …”. Organisations need to consider how they can employ PSWs who are genuinely in a position to offer ethical and effective alternatives, otherwise there is a risk of organisations “using peer workers to create the appearance of recovery orientation, human rights compliance or community integration12” when this is far from the reality.

The employment of PSWs is only one way of working towards the development and delivery of recovery-focused, rights-based, person-centred, community-integrated services. If they are seen as the only way of changing services they run the risk of becoming crushed by the responsibility.

3.3 Ensuring shared understanding about the role of PSWs

The most common difficulty reported by both peer support workers and their non-peer colleagues is lack of clarity about their role. Both peer workers themselves and the staff with whom they work express confusion about what PSWs are employed to do and whether this should differ from the role of other support workers.

PSWs are not employed to deliver therapies or treatments based on professional training, nor are they employed to undertake all of the duties of non-peer care/support workers. They are employed to offer time, care, support, active listening, problem solving, ideas, suggestions and practical help within trusting, mutual, unconditional relationships with people using services – based on their experiential knowledge rather than on the traditional psychiatric knowledge taught to other professional groups.

While training for PSWs should provide clarity over how PSWs work (the values underpinning their approach), it is the organisation or team in which they are employed which needs to define precisely what is expected of them in that setting. In order to both create appropriate job descriptions, and to ensure that the whole team/organisation understands the nature of peer support, it is essential to provide all team members with information, preparation and time to discuss possibilities and opportunities for the team to define and understand everyone’s roles: the values and tasks that are shared as well as their distinct contributions. To date, most evidence of the impact of PSWs has been generated in settings where peer workers support transitions into and out of services, such as facilitating discharge or movement into community groups or employment, or into other services (such as transitions between Children and Adolescents’ services and adult mental health services).

However PSWs are increasingly working across the whole spectrum of services – forensic, substance misuse, intensive care, assertive outreach, crisis teams ….13 Wherever they work, it is essential for them and the team to respect their peer values and to support them to offer their distinct knowledge and skills to complement other members of the team.

3.4 Learning from peer led groups and VHSE organisations

The vast majority of peer roles exist within third sector and voluntary community groups, user led groups, self-help groups, housing services and organisations for homeless people. Much has been written about the risks incurred in ignoring the wealth of experience about peer support that has accumulated in these settings14.

Many of these groups have their roots in civil rights, in developing alternatives to psychiatric services, protesting against current practices and treatments, in believing in one another and finding ways forward through mutual support and solidarity.

They often have a closer understanding of the issues that are most important to people who experience mental health problems: issues like social justice, human rights, understanding diversity and appreciating the implications of traumatic life events, that are too easily overlooked in professionally led statutory services where greatest emphasis is often placed upon treating symptoms.

When organisations are preparing to employ PSWs, they are well advised to work in partnership with (other) user led and third sector groups within their locality, this can help to ground developments in first-hand experience and to resource and inform training, supervision and recruitment.

3.5 Enabling teams to understand and support PSWs role and contribution

Wherever PSWs are employed, team members need time to think through the implications of changing the relationship to a collegial relationship of equals. Often there is genuine concern for the wellbeing of PSWs, how they will cope with the demands of the work and exposure to others’ distress; how they will demonstrate/embody recovery and hope if they relapse at work; there is also concern about their ability to maintain professional boundaries and respect confidentiality when they are supporting people who are their peers – indeed they may be friends, or have shared time on an inpatient ward.

Team members need to be clear about how PSWs have been trained, recruited, selected and how they will be supervised. This cannot be achieved simply through giving information, it will only be understood through discussion and freedom to share personal views in a safe space.

Staff may also have concerns that PSWs won’t understand ‘why we do the things we do’: having first-hand experience of using services means that PSWs are likely to be sensitive to non-recovery focused practices and documentation, negative language, assumptions and ‘gallows humour’.

When employed in a context that welcomes feedback they can have a significant positive influence on team culture15. However, without preparation, team members may find feedback from PSWs difficult to hear and may become defensive. With preparation of the whole team, with time for reflection, discussion and development of a whole team approach to welcome and facilitate peer support workers to contribute to team development, team members can be supported to recognise the ideas and suggestions from peer workers as helpful and constructive.

Peer workers are trained to work within different relational boundaries from other staff. Since they will, by definition share more of their own stories, they are likely to hear more about the experiences of those whom they support. The team needs to prepare for this, consider what it means for the way they work, how they can value the lived and life experience of the whole team, how to share information and where confidentiality is critical.

Members of the team who bring lived experience of mental health problems may wish to undertake additional training on how to use their own experience appropriately and effectively in their relationships (although their role, power, code of conduct and professional source of reference means that they can never substitute for PSWs). Conversely, without careful preparation, organisations and teams can create a context in which PSWs comply with current practices, adopt the values and principles of other workers and lose their distinct identity, role and capacity to improve the culture.

3.6 Creating supportive, accessible and effective recruitment processes

Some people applying for PSW roles will have been out of paid work for some time – often many years. This can make the process of applying for a job, filling in application forms, completing DBS applications (police checks) and preparing for interviews stressful and off-putting. Care needs to be taken to recruit PSWs with a range of experiences and cultural backgrounds, recruiting from grassroots community groups, third sector organisations and services for groups that find services difficult to access – it is with these groups that peer support can be most effective16.

Personal support and information, feedback about the process as well as appropriate adjustments will help to make application less daunting and more accessible. Although this, once again, reflects good practice with all staff, it is often not available for any potential applicants and by improving HR and Occupational Health processes for peers, lessons can be learnt to improve the experience for everyone.

Once in post, support, supervision and development opportunities are essential. Training for PSWs is frequently quite brief and, as with many professions, learning really begins once they are in post. Accessible support on a day to day basis is helpful to reduce anxiety and answer questions as they arise, but peer specific supervision is essential to facilitate development and ensure that they maintain their ‘peerness’. Organisations need to make decisions in advance about who will provide managerial and peer supervision and how critical issues will feed back into organisational development, training available and specification of peer support roles.

4. Preparing the Organisational Context

4.1 Making Peer Support everybody’s business

Any organisation considering the employment of PSWs, needs to ensure that this is not a ‘niche’ discussion happening in one team; something that is slipped ‘under the radar’ in order to make it happen without the potential for barriers, or something that is considered insubstantial and a tick box activity to gain funding or achieve CQC approval.

The employment of PSWs does not happen as a separate, one-off event. It will trigger wide spreading ripples across the whole organisation, raising questions with far reaching implications. For example, an organisation cannot employ people specifically to use their own lived experience (PSWs) if it does not explicitly value the contribution of all staff who bring personal lived experience.

It is not enough to simply state that these staff members are valued, this has to be demonstrated in recruitment, selection and employment policies practices; managers need to be able to access training so that they can provide appropriate employment support; training must be available to clarify how these staff can use their personal experience safely, appropriately and effectively.

If implemented carefully, the employment of people with lived experience explicitly to draw on their own experiences in order to support others has the potential to significantly change the experience of people using services and shift the culture of the organisation.

If implemented without care and attention it has the potential to harm the PSWs employed, reduce the readiness of all staff to disclose their own lived experience, damage staff attitudes and belief in recovery, reduce the likelihood of recovery focused cultural change and ultimately it is people who use services who will suffer. It is preferable not to do it at all than to do it badly.

This means that the first step is to set up a peer support advisory group with membership from all levels of the organisation (for example, senior service manager, executive sponsor, HR/OH representatives, learning and development representative, user and carer involvement lead, service user representatives and where possible Recovery lead), and from any userled or peer support organisations working within the geographical system of services who can offer experience of employing PSWs.

This advisory group needs to make itself aware of what PSW means, the potential benefits and pitfalls, organisational requirements (eg for development of new training courses) and implications (eg for funding of project lead, funding for new posts, review of employment support for staff with mental health challenges).

At an early stage, the decision can then be made about whether the organisation is ready to embark on this process or not, and if they are, who else needs to be invited to join the advisory group (eg local voluntary and third sector peers; experts from other organisations with prior experience, team leaders where peers may be employed …) and who will take on the role of project manager.

4.2 Board level support for peer support workers

Even at this early stage, there are potential action points for all members of the steering group. Since the employment of PSWs is a significant decision with wide ranging ramifications, the Executive Sponsor for PSW (or a designated link person with the board) will need to present a proposal to the Board and both ask and answer questions from the Board.

Of primary significance is Board level recognition that the employment of PSWs signifies that the organisation recognises the benefits and value of experiential knowledge. At Board level, it is essential to consider what this means for organisational strategy and whether changes are required to ensure that this message is clear and consistent in all aspects of the organisational vision and strategy.

The employment of PSWs is a necessary but in itself insufficient element of overarching transformation towards services in which relationships between service providers and service users become more equal as they work more collaboratively in shared decision making, coproduction, collaborative care planning, joint safety planning and cultural shift towards valuing the preferences and wishes of people who use services.

If there is no organisational commitment to this overarching shift then the opportunities for PSWs to work in distinct person focused, experientially informed ways is likely to be limited to a role in which all that is shared between peers and those they support is their mutual powerlessness. Alternatively, if the organisation is prepared to value the perspective of PSWs and people using services, opening itself to new ideas and willing to try innovative coproduced practices, then the pool of resources available is expanded to include all those using services17; practices become more recovery focused and the experience and outcomes of people using services are likely to improve18.

4.3 Funding

An important element of organisational commitment to PSWs is allocation of adequate funding. PSWs employed within an organisation must have the opportunity to apply for paid posts, banded according to job descriptions. They are not a cheap alternative to professional staff, they are an effective complement to multidisciplinary teams. As with any professional group the PSW budget needs to cover costs of developing PSW training, preparing teams, providing supervision, and professional leadership.

4.4 Leadership

It will take time for numbers of PSWs to reach a critical mass – able to present a case or provide effective support – within a single organisation. This makes the appointment of a peer support leader essential. It cannot be assumed that PSWs will be appropriately led by other professional leads.

Peer Support arose in a totally different philosophical and practical tradition; one which largely developed as a response to poor treatment and neglect within services19,20. It may be helpful for an existing user and carer engagement lead, or a Recovery lead to be appointed to lead the development of peer support but thought needs to be given to the experience and capabilities of the appointee. A peer support lead must bring their own lived experience and demonstrate appropriate and effective disclosure of this, ideally with working experience as a peer support worker themselves. More information on this can be found in the Thought Piece on Career Pathways for peer support workers.

They need to understand the politics and practice of peer support and have strong links with networks of peers locally and nationally.

But they also need to understand how organisations and traditional professions work. They need to have excellent communication skills to gain the respect of other professions and above all strong leadership skills to take forward new peer roles and enhance their influence across organisational culture (see Case Study 3).

This is a demanding and potentially isolating position as a central aspect of the role is to provide challenge at all levels (including the Board) from a lived experience perspective. There are organisations that recruit service user/peer leadership from external organisations, this has the advantages of proving a more independent voice when challenging the system; however the person may feel of a lone voice if they operate from within a separate organisation; they can discuss, test and develop a service user perspective within a collective of peers (see Case Study 1).

Case Study 1: Trust wide Lived Experience Practitioner & Peer Support Lead role within Central and North and West London NHS Foundation Trust (CNWL)

My role as Trustwide Lived Experience Practitioner & Peer Support Lead for a large NHS Trust in London is nothing if not large and varied. I hold responsibility for the strategic development of our workforce, which includes developing infrastructure, and advocating for the creation of new roles.

I also supervise a large (and growing!) team of senior peer support workers and advanced lived experience practitioners, and co-deliver our Level 4 accredited ‘Developing Expertise in Peer Support’ training at London South Bank University. I frequently present our services both internally and externally, and liaise with stakeholders, such as colleagues within other professional groups, HR, recruitment, volunteering, service user and carer involvement, our employment services, and the Recovery and Wellbeing College. Much of my work, therefore, is about building relationships and communicating vision.

I am amazed at how critical my previous experiences of working within a variety of peer roles serve me day to day. Prior to my current role, I have worked across both inpatient and community settings, in both statutory and User Led Organisations and the third sector. This varied experience of peer roles across my career feels absolutely integral in being able to provide credible, and experientially informed leadership to my colleagues.

Furthermore, I often speak about holding a caseload of one – my organisation.

At CNWL we define recovery as “the purposeful pursuit of a good life, irrespective of the absence or presence of symptoms, organised around the pillars of hope, opportunity and control, with social inclusion and self management at the heart.”

Much like many of us who have experienced mental health difficulties, my organisation has come a long way and done well in working towards developing a focus on recovery. However, it is on an ongoing journey of recovery, which we all know is a non-linear journey by nature. From having skills honed in ‘front facing’ work, I am able to think about how to use myself, a relational way of thinking and some smatterings of self disclosure to support the system to consider another way of considering its contemporary circumstances.

Using a similar approach to staff supervision, I work by focusing on sharing a relationship where we can both learn from each other, neither of us is positioned wholly as the expert, though we have different useful perspectives to communicate and tasks to achieve in our respective roles. This allows an ongoing development of this perspective and keeps alive my skills as a lived experience practitioner. I am always keen to learn from my colleagues, and I usually find that my grounding in approaching people I work with as keepers of their own wisdom fosters a mutually curious and open way of us both relating to each other.

5. Organisational Preparation: A checklist of questions to address

Any organisation planning to employ PSWs will need to consider a number of key questions. These are summarised below and more information to inform responses is provided in the following sections.

What do you want to achieve by employing PSWs? (see Section 3) As an organisation are you committing to working in partnership with people who use services in every way possible? Are you employing PSWs to demonstrate your belief in people who have experience of mental health challenges? To improve the experience of people using services? How are you going to make this commitment understood, shared and ‘real’?

How will PSWs be employed? (see Section 6.1) There are various different models for employing PSWs and no conclusive evidence about which works most successfully. Have you considered whether you will work in partnership with an external organisation to train, supervise and/or employ PSWs, or whether you are going to employ them in house? (see section 6 for more details about different options).

Where will PSWs be employed? Are you working towards employing peer workers across the whole service, one part of the service, or one team…? Where are you going to start and what is the goal? This may be informed by where funding is available, where new services are being developed, where quality improvement initiatives are being implemented.

However, decisions made by managers about where, how and how many PSWs will be employed are unlikely to be as successful as engagement with teams about what peer support is, what it can achieve, whether they are interested in employing PSWs on their team. It is essential to include members of teams where PSWs will be employed in the planning process, ideally as members of the advisory group. The employment of two or more PSWs in each team is strongly advised so that they are not isolated and have some mutual support from other peers whilst they are carving out a role and a distinct identity for PSWs in the team.

How many posts will be developed? Whilst it is advisable to start with a small group of PSWs so that sufficient care can be given to refining processes and support mechanisms, the PSWs will feel less isolated and alone if the first group includes around 12-18 peers.

This allows mutual peer to peer support, meaningful experiential learning, sufficient numbers to have a collective voice and a sense of solidarity – and it thoroughly tests processes and practices from the start. Some PSWs do not feel ready for full time posts from the start of their employment so, as a rough guide, it is likely to be necessary to train up to 18 PSWs to fill 6 FTE posts.

How will PSWs be recruited, selected and supported during and following the application process (see Section 7) Decisions need to be made about HR leadership for the safe and effective recruitment, selection and employment (support) for PSWs, including occupational health support.

How will PSWs be trained? (see Section 9) Provision needs to be made about the training of the first cohort of PSWs and then for ongoing learning and development of this cohort as well as new recruits.

How PSWs will be supervised (see Section 10) Since peers are much more likely to retain their peer identity and role if practice supervision is offered by an experienced PSW, arrangements need to be made for this to be offered whether in-house (possibly with support or through an external organisation), or by an external organisation from the start.

How will development opportunities be created for PSWs? (see Section 10) Consideration needs to be given to the ongoing career pathways for PSWs, opportunities need to be developed within the organisation for PSWs to progress into (eg senior peer roles, team leader roles, lived experience practitioners, peer specialists). In addition, PSWs bring lived experience to the whole organisation and some of their time might be set aside for coproduction activities alongside the user and carer involvement service or for developing coproduced learning opportunities either in the Recovery College or in staff learning and development courses.

How will existing staff with lived experience be supported? (see Section 9) The employment support provided for PSWs should not be exclusive to these members of the workforce but must be extended to all staff members so that everyone can work to their full potential and stay well in work21. Additionally, although PSWs are employed specifically to draw on their experiential knowledge, many other members of the workforce will have experience that could be used in their practice to enhance the support that they provide. This has implications for Human Resources, Occupational Health, Learning and Development and managerial roles.

How will observations, perspectives and suggestions of peer workers be responded to? (see Section 11). PSWs are employed not only to support people using services, they also bring a different but equally valued perspective to services and service development. Whilst individual peers working in teams might find it difficult to make their voices heard, a forum where PSWs can join together to share experiences, develop their views and suggestions and take them forwards for consideration by relevant forums is an important indicator of the real value that is afforded lived experience.

Who will employ, train and/or supervise the PSWs working in your organisation? Peer support has its roots in peer run organisations and where there are local peer run organisations it is essential to work in partnership with them to ensure that the original values and principles of peer support continue to inform PSW practice. Without this, PSWs too often become no more than ‘peer staff’ who end up complying with traditional psychiatric practices rather than bringing their distinct and unique peer contribution.

The experience and solidarity of peer led groups not only support the integrity of peer practice, they can also provide a safe place for PSWs to share their experiences, discuss challenges and develop responses. However, employment in paid roles within large, often statutory organisations does bring different challenges, expectations and limitations. The governance, bureaucracy, hierarchies and power relationships within these organisations can make the employment of PSWs a tightrope act – trying to retain peer principles within settings in which many people using the services are highly distressed, may be on involuntary sections of the MHA, where (professionally defined) safety is the priority.

While partnership between peer-led organisations and statutory organisations is always preferable, decisions have to be made about where and how PSWs will be employed.

6. Who will employ, train and/or supervise the PSWs working in your organisation?

6.1 Employment of PSWs by an external peer support organisation.

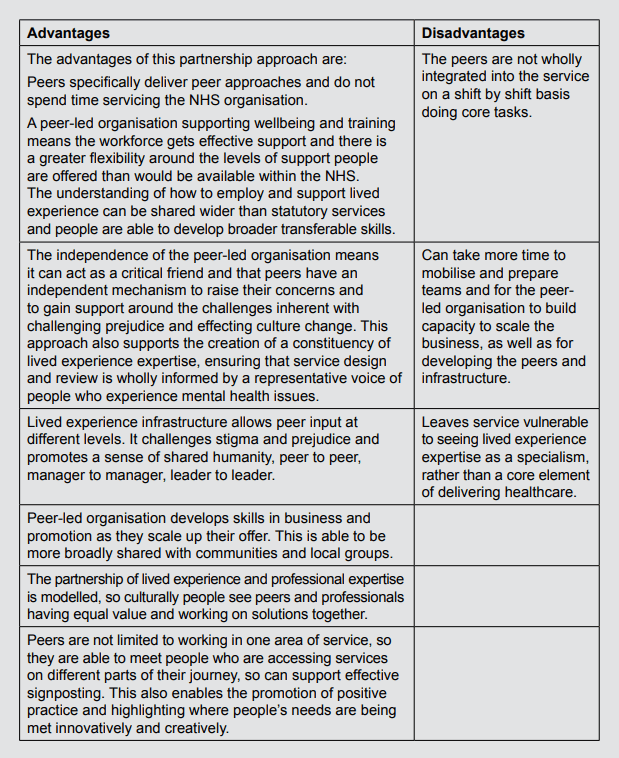

The training, role, employment and supervision is all undertaken by an external (peer-led or experienced in peer support) organisation and PSWs are placed in posts in a mental health service. This requires close collaboration between the two organisations so that expectations are consistent. Communication needs to be clear to anticipate and prevent problems arising, pathways for conflict resolution need to be set up in advance. (see Case Study 2)

Case Study 2: Dorset Wellbeing and Recovery Partnership

Dorset Healthcare University NHS Foundation Trust and Dorset Mental Health Forum have been working in partnership, as the Dorset Wellbeing and Recovery Partnership (WaRP), for the past 10 years. At the heart of this Partnership has been the exploration of lived experience and clinical expertise co-existing to provide a range of perspectives.

Dorset Mental Health Forum is a local peerled organisation, employing approximately 80 people all of whom have their own lived experience of mental health challenges, or that of supporting partners or close family members. The aims of the Partnership are to change the culture of mental health services and promote wellbeing across the whole of Dorset. Through this work, the Partnership promotes and models shared humanity and the belief that Recovery as a philosophy is common to us all.

In Dorset, peer specialists are independently recruited, employed and supported by the Dorset Mental Health Forum and they then work into Dorset HealthCare. Peers work at different levels into inpatient settings, CMHTs, CAMHS, specialist services (such as Forensic, Perinatal), the Retreats (open access crisis service), Learning and Development, and the Recovery Education Centre. The Forum do not just provide peers to deliver services, but also work strategically on the Mental Health Integrated Programme Board and at team leader level to support service development, as well as influencing at Board level and as system leaders within the local Integrated System (ICS).

The Forum has developed a career structure, referred to as a lived experience infrastructure with peer specialists, peer coordinators and lived experience lead posts. Over the past 10 years, the Partnership has been able to test and demonstrate that this independent way of working adds value and also provides an additional mechanism for peer support within the organisation itself. Much of the work independent peers do, includes compassionate challenge and building a sense of collective community informed from a range of perspectives.

The work is underpinned by a codeveloped partnership agreement, which acknowledges both organisations as stakeholders and partners in decision making and planning. This enables explicit conversations to happen around power and the direction of services. The partnership agreement also covers how risk is managed, data sharing and confidentiality.

Before peers work into a new area of service, the Dorset Wellbeing and Recovery Partnership leadership team (with a representative from the Forum and a representative from the Trust) engage in some team preparation and culture focused work. This also provides an opportunity to provide assurance of how peers are supported to do their work. Wellbeing at Work plans and Advanced planning documents are discussed, as well as details and descriptions of ongoing training, supervision and support mechanisms that are in place.

It is often important to teams that they are able to explore how they can build capacity from within their own services, so we discuss how we might engage with people who have previously accessed their service and how a pathway may be developed.

6.2 An external organisation provides the whole service

The whole service is commissioned from a peer run organisation which runs independently. (see Case Studies in HEE thought pieces on a) Crisis Services where the Cellar Trust is commissioned to provide peer led services, and b) VCSEs and Peer Support).

6.3 The organisation recruits, trains and employs its own PSWs

The organisation that wishes to offer peer support develops systems and processes for recruiting, training, employing and supervising peer support workers. PSWs are employed either in selected multidisciplinary teams or from a central peer support team. Wherever peers work, staff are given preparation so that all members are clear about the role and employment conditions of PSWs. Practice supervision is provided by peer supervisors (who may come from external organisations) whilst their team leader provides managerial supervision as with other members of staff. (See case study 4)

Case study 3: Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust

In 2009, as an ImROC Pilot Site, CNWL began its journey to transform our workforce through establishing peer support activities in a statutory service at a time when such an endeavour was considered innovative. As an organisation, with executive support, we aligned the development of our Recovery College and peer support to work closely together. Subsequently the staffing resource for both was strongly linked; peers were trained together via an in-house provided training programme, and initially some staff worked across both workstreams – as both peer trainers and peer support workers.

As time has gone on, we are glad to have initially ventured forward with the model of in-house employment. The influence of peer support workers being embedded within the organisation has paid dividends in terms of our organisational culture shifting towards a recovery focus.

Though there is still work to be done, one of the huge benefits of all peer support workers being employed directly by CNWL, is the way in which ownership and pride for these roles is rooted in many colleagues at all levels of our organisation. It is hard to say whether we would have quite the same level of support for the work we are doing to improve, upscale and innovate, if our efforts were all located within an external partnership organisation.

We have found that what follows embedding peer support organisationally, is broad support for the recovery focused agenda. Issues that peers advocate for, such as coproduction, informed and shared decision making, reducing restrictive practice and trauma informed care for e.g; are increasingly being considered ‘everyone’s business’.

Additionally, the feeling of ‘us and them’ between peer workers and other colleagues is reduced as our staff feel the benefits of working alongside their peer colleagues. As ‘mentally healthy’ workplace cultures are required for our peer workers to thrive, our working practices and policies continue to evolve with benefits of improved workplace wellbeing and job satisfaction for all staff.

Some NHS Trusts have successfully achieved a similar level of embedded presence via strong partnership working with local VCSE’s. For us at CNWL however, considering the sprawling geography and size of our Trust, we feel our peer workforce, located within the organisation, allows us to effectively work collaboratively across the whole organisation. In such a large organisation it is critical that our peer colleagues are not forgotten or undervalued. By developing an in-house workforce; we work alongside each other, ensuring delivery of services that reflect our Trust’s values.

7. Human Resources and Occupational Health issues

7.1 Developing the job description – what will PSWs do?

It is advisable for the whole PSW advisory group to be involved in determining the role of PSWs by contributing to the development of their job description. There are critical decisions to be made about what will be expected of PSWs. It is helpful to start by reaching agreement about how your organisation wants to define peer support, what you want to achieve by employing PSWs and how their job description can be crafted to stay true to your goals.

The literature suggests that peer support workers make at least three distinct contributions that differ from other staff22. The first is the development of a relationship characterised by mutual understanding, acceptance, trust and a genuine belief in the person’s ability to recover. The second is the inspiration of hope through self-disclosure; demonstrating that it is possible to gain control over mental health challenges, from being defeated and disabled by the condition to understanding it and believing that it is possible to live well in spite of, or even because of the condition.

The third lies in sharing experiences within this trusting and more equal relationship, exploring ways of coping and managing the condition and life more generally. This might include identifying life goals and working out steps to achieving them, it might mean problem solving together, developing a personal recovery plan, or practical help to address barriers – both within services and the social situations that stand in the way of living well – things like debt, poor housing, relationship problems.

While PSWs might not have the answers to these problems, their job description needs to allow them to spend time with people, help them gain understanding, work out what their experiences mean to them, work with them to think about what they want, find out what is available, what might help them, and then to take action together.

Having agreed on the purpose of PSWs in the organisation, it can be useful to look at a range of job descriptions developed by other organisations and then to consider key questions about the role of PSWs in relation to certain tasks and whether they will they be included in the ‘numbers’ on a shift.

Will PSWs be expected to undertake the routine duties of other support workers (like making beds, serving meals…) or will their role be confined to supporting Recovery through one to one support, running groups, coaching, recovery planning, goal setting, action planning….?

There are different ways of addressing these questions. Whilst the question of whether PSWs will be included in the ‘numbers’ is largely informed by finances, questions about the nature of their role are largely addressed by considering the values underpinning the role. PSWs are not employed to carry out tasks and duties defined by other professionals but to engage with people in a mutual and reciprocal manner. They may be able to achieve valued relationships whilst undertaking such tasks as making beds together, attending meetings together, taking a walk together or planning action together, but these tasks must not take precedence over relationship building and peer support.

More contentious questions must be addressed in relation to the role of PSW in coercive practices: the values and principles of peer support mean that PSWs should not take part in restraint or in giving medication – or other treatment – against a person’s wishes.

However, there are ambiguous situations in which a PSW may be involved in preventing a person from harming themselves or someone else; they could have a role to play in reducing a person’s distress, de-escalating a crisis, taking them for treatment that they have agreed to but may well be frightened about…. It is essential that a wide range of stakeholders are involved in discussions about the role of PSWs in your organisation so that a deep understanding is achieved and well justified decisions are made.

7.2 Person specification – what do you mean by ‘peer’?

One further crucial question to be considered relates to the person specification: what do you mean by ‘peer’? Whilst PSWs working in mental health services might be expected to have personal experience of mental health problems, it is important to think about how this will be defined. Will people define themselves as having this experience or will they be expected to have used services? if so, will they need to show they have used primary or secondary services? Will you consider people who have sought personal therapy to have the shared experience necessary to provide peer support?

Given that so many people using mental health services have experienced trauma, homelessness, poverty, unemployment … will these factors be taken into consideration when recruiting PSWs? Will your definition of ‘peerness’ depend on the service that you are recruiting to? For example, when recruiting PSWs for forensic services, will PSWs be expected to have used forensic services? When recruiting PSWs for homeless services will they be expected to have experienced homelessness and/or mental health problems?

An advisory group which includes people with a range of experiences, perspectives and a deep understanding of peer support will be helpful in reaching well justified answers to these questions.

7.3 Recruitment

However many peer support workers will be employed and in whatever part of the services, consideration needs to be given to the recruitment and employment process. Since PSWs bring added benefit for the engagement and recovery of people who find services difficult to engage with, it is advisable to recruit some PSWs from groups who themselves have difficulty accessing and engaging with services.

Recruitment needs to reach people who have experience of adverse life circumstances and mental health problems who are no longer using services, so advertisement of posts needs to go beyond NHS Jobs to provide relevant and accessible information to local voluntary sector, local authority and primary care groups and services.

For recruitment processes to be accessible, it is helpful for clear and welcoming advertisements to give the name and phone number of someone to call if they are interested in finding out more about the post. Calls must be returned quickly and supportive – and honest – responses given to inquiries. Peer support is not an easy job, it is not well paid and it does require people to talk about their own experiences.

However, if you want to use your experiences to help others, if you have found ways of managing your own condition and living well, then it might be for you.

The application process for large organisations can be a deterrent in itself. It requires access to a computer and the internet, a high level of literacy – and it asks questions about past employment and experience. All of these might be particularly difficult for people who could make very good PSWs.

It can therefore be helpful to offer individual support to people interested in applying to become a PSW, enabling them to access the right form and giving them the confidence to respond to questions appropriately. This might be undertaken by a member of the HR team or the employment support team, or once there are PSWs in post, it might be possible for a member of the PSW team to provide this support.

7.4 Selection

Just as applicants for PSW posts have often had little experience of applying for work, they may also find the prospect of an interview very anxiety provoking. It can be helpful to arrange a selection process that allows applicants to demonstrate their skills, values and behaviours in different scenarios.

An assessment centre approach in which all shortlisted applicants are given the opportunity to meet, ask questions, take part in a large group discussion, answer selected challenges in a small group and take final questions in a brief individual interview can be a more effective approach to selection. It is essential for the selection team to include at least one person with lived experience, ideally already in post as a PSW, and for an HR representative to sit on the panel to answer questions about process and expectations, as well as a service manager/team leader from the service the successful applicant will work in.

As with all recruitment, it is necessary for the panel to agree set questions and criteria beforehand. In order to work well as a PSW, applicants do NOT need to be symptom free, but they do need to demonstrate an understanding of their condition, what they do to keep themselves well, how they know when they are not so well and what they do when they need additional support.

Indeed, it is the learning that has occurred through their own experience that will be most helpful in their role as a PSW, so selection does need to assess what they have learnt and how this might enable them to support another person. Since peer support is built on strong values, it is helpful to observe group discussions and problem solving for evidence of applicants’ values in action.

All applicants, whether they are offered a post or not, should be given feedback so that they are clear why they were successful or unsuccessful and for those not offered a post, support should be offered to enable them to develop their skillset (for example an introduction to Recovery College to learn more about personal recovery planning, an introduction to the Volunteer team for opportunities to gain more experience in supporting others).

7.5 DBS checks

For people who have been involved in the criminal justice system during difficult periods in their life, the prospect of completing a police check form is yet another barrier to negotiate. Personal support and information can help them to see this as just one part of the process of applying for a job. However, at an organisational level, the employment of PSWs may well trigger a review of the DBS checking process.

7.6 Employment support

The introduction of peer support workers in the workforce provides an opportunity to consider and develop new strategies, policies and procedures for the benefit of all staff. Line managers and leaders should be supported to adopt a zero tolerance towards discrimination. Policies as part of a wider plan to implement and communicate the importance of wellbeing could be introduced.

- Occupational Health assessments are a routine part of NHS and larger organisations usual recruitment processes. While they are designed to assess the health needs of a new employee and offer support to fufill the duties of their new role, they can be particularly anxiety provoking for peers who may have been denied employment because of their health condition or been “retired” from previous employment due to their health condition.

The success of these assessments depends on the level of understanding of the person carrying out the assessment ie do they understand the role? Do they understand the duties expected? Do they appreciate/ understand why the person may not have been in work previously. It is Occupational Health who will make recommendations about reasonable adjustments, again the nature of the adjustment recommended will depend on the OH professional truly appreciating the role and context in which the person will be working.

- Reasonable adjustments. Employers have a duty of care under the Equality 2010 and Reasonable Adjustments DWP 2017 give some guidance on employing people with mental health conditions. DWP suggest flexible work patterns, changing the work environment where possible, creating action plans to help manage their condition and allowing leave to attend appointments and so on as helpful strategies but these do not go far enough. Reasonable adjustments can and should be made throughout the recruitment process as suggested in 7.3 and 7.4 of this paper to ensure peers are supported appropriately to successfully apply for roles and survive and thrive in work.

- ‘Wellness at Work’ plans. Peer support workers benefit from understanding how ‘Wellness at Work’ can help them in their employment, so this should be an integral part of their training as well as part of a more general approach to having open and honest conversations about mental health in the workplace (something which all staff would benefit from). A wellbeing plan helps to build a picture of why a person may react in unexpected ways to situations and enables support to be provided based on shared understanding, regularly reviewing the plan is important and can be done as part of ongoing supervision.

- Occupational Health Support. Ongoing support from OH may be necessary for the peer support worker to remain in work. OH may be best placed to recommend and signpost PSWs (and others) to additional support Eg Employee Assistance Programmes, and initiatives like the “Green Hour” implemented at CPSL MIND that encourages all staff to have an hour a week in “work time” to play sport go far a walk, read a book etc.

7.7 Financial considerations for peer support workers

Due to the complexities and individual nature of our current benefits system we would recommend that ALL peers applying for peer support worker role should seek individual benefit advice.

Many peers work part time or on “bank” arrangements which further complicates how peers can be paid and employed. Some peers choose to begin their employment under permitted work and assume that they will be able to work for 16 hours and earn under a set amount per week that is usually 16 hours times the national minimum wage.

For entry level Agenda for Change band 3 PSWs this isn’t the case. The hourly rate of pay for a band 3 PSW is higher than the national minimum wage which means currently peers are only able to work about 12 hours / week to meet the requirements of permitted work.

Again, we would advise seeking the advice of an employment advisor if you have access to one or the Disability Engagement Officers at DWP. NHS Trusts will have access to pensions advice to support peer support workers to think about their future pension and to understand the importance of national insurance contributions in safe guarding their future financial security and we recommend that PSWs are encouraged to meet with their advisor as part of their induction programme.

Trusts are used to employing staff who are managing long-term conditions or have a disability, and, therefore, it will be helpful when employing PSWs for the first time to apply similar “rules”.

8. Team Preparation

The success of PSWs is largely attributable to the teams in which they work. Where the team understands why PSWs are being employed, how they will contribute and what additional specific support they are able to offer to people using the service PSWs can settle in without confusion, negative judgements or blame. Where team members actively seek out PSWs to provide mutual support to people who are isolated, disengaged, inactive or experiencing distressing experiences, then peers use their skills in a targeted way, they feel valued and appreciated by staff and people using services and given support and supervision they will enrich the team, improve the experience of people using the service and develop their own skills and confidence.

8.1 Team Preparation workshops

Once decisions have been made about where PSWs will be employed, then each team needs some careful and bespoke preparation. Where possible the whole team (including all professions and non-clinical staff) needs to spend at least half a day sharing, learning and planning together.

The session needs to be facilitated by the peer support lead, a senior service manager and a peer support worker. It is helpful to cover the following areas in an experiential, non-judgmental, and developmental manner and to create a safe space for all participants to contribute openly23:

- Peer support: What is meant by peer support, what is a PSW, what do they do, what difference do they make (input by PSW lead).

- What are the hopes and fears of team members about a PSW joining their team (generation of ideas to be done confidentially so that participants can be honest) (exercise facilitated by PSW trainer)

- Which of these fears can be addressed here and now? What further information is required to address all the concerns raised? (Manager to lead discussion of feedback)

- How can the team ensure that all their hopes about PS are realised? (Manager)

- What is the role of PSWs in a team like this (PSW lead drawing on examples from literature and practice)

- How will this work in your team? How could a PSW enhance the support that you offer? (exercise facilitated by PSW trainer) Collect a team specific list of PSW tasks/duties

- How can you, as a team set up processes and support to enable your PSWs to work to their full potential (eg how to refer/ engage PSWs in specific work with people using the service; identifying a mentor for PSWs…) (exercise facilitated by PSW lead)

- Making an Action Plan, identifying who is responsible for what and when.

8.2 Can PSWs work in any mental health team?

Since PSWs bring experience of using the whole range of mental health services (some have used acute inpatient services, some community, some substance misuse services, others child and adolescent or forensic services; some have avoided using services but have sought different types of support , therapy and/or treatment …. ), in theory they can be employed to work in any of these services so long as they potentially share some of the experiences of people currently using those services.

However, it is particularly challenging for PSWs to be employed in very traditional, hierarchical or coercive teams where there are no plans or attempts to introduce more Recovery focused practices. If a PSW is employed in a team where there is frequent restraint, where the emphasis is on giving medication and treatment against the will of people using the service and where there is little attempt to share decision making or facilitate personal Recovery planning, then PSWs will not be able to work in a manner consistent with their role.

Too often, PSWs employed in contexts such as this become disillusioned, frustrated, burnt out; it is not fair or ethical to place them in contexts which will either be bad for their wellbeing – or require them to adapt and adopt accepted practice.

This is why the introduction of PSWs cannot be a standalone initiative: the only intervention implemented to challenge current practice. This places huge responsibility on individual PSWs and essentially sets them up to fail in their role. Organisations introducing PSWs need to consider how other initiatives might support and strengthen the influence of PSWs in changing the culture of the organisation.

8.3 Team Recovery Implementation Planning (TRIP)

One approach that complements the introduction of PSWs in teams is Recoveryfocused quality improvement using the TRIP as a set of benchmarks for the team to assess themselves against, identify 3-5 priorities for action, and agree a comprehensive team recovery action plan that can be reviewed regularly.

The introduction of TRIPs to improve the Recovery focus of teams has been a CQINN target in a number of areas (including high secure services) and used in outcomes-based commissioning. It is worth considering the use of TRIPs in organisations where teams are not actively working towards Recovery before employing peer support workers24.

8.4 Ongoing support for teams employing PSWs

A single workshop to prepare a team for PSWs is unlikely to provide sufficient understanding of what will be required, nor will it facilitate the ongoing development of structures to support and develop PSWs in practice.

Where PSWs are employed, team leaders need to have access to support, problem solving, coaching and development to enable them to continue to develop a supportive context for PSWs and to manage any challenges that occur in an appropriate Recovery focused manner (see also Section 9).

9. Learning and Development Opportunities to support the employment of PSWs

9.1 Training in peer support

It is essential for all PSWs in paid roles in organisations to undertake high quality training in peer support that enables them to understand the values and principles of peer support, implement these in developing relationships and to work safely, appropriately and effectively. Organisations may wish to access PSW training provided by respected organisations, and they may wish to work with these organisations to develop their own PSW training course.

HEE is currently working with UCL partners and the NCCMH to develop and approve a competency framework for PSWs which clearly outlines the areas to be covered by training. Once this has been ratified, trainers will have a shared consistent and agreed framework to inform the development of training. (Contact HEE for information about training providers.)

A number of different organisations offer PSW training at different levels, some accredited, some not. (See ImROC Training Prospectus and ImROC Peer Support Brochure).

Case Study 4: PSW Training provided by ImROC

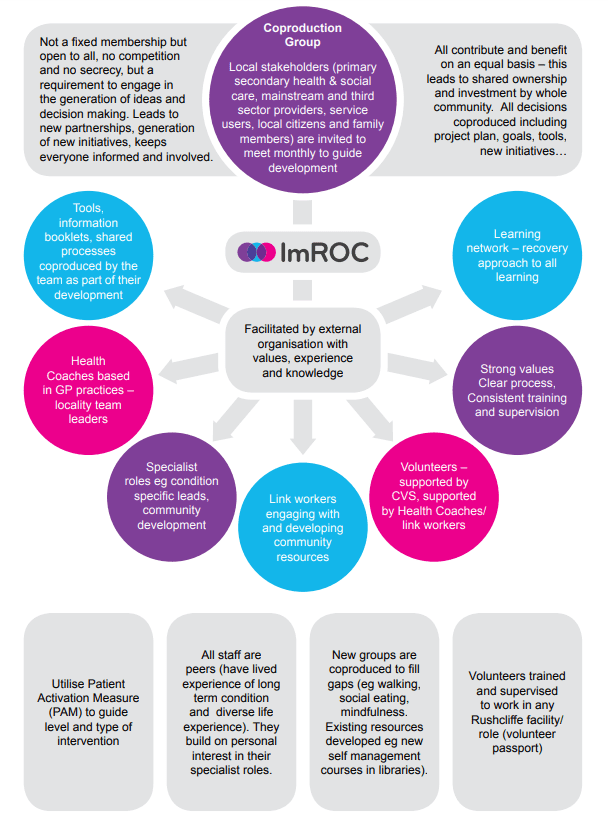

ImROC coproduced the first training course for PSWs working in NHS services in 2008 working with local peer led NGOs and drawing on an extensive review of the literature. This course has developed over the past 12 years and is now offered as organisational development support rather than simply a training course.

A team of experienced peer and professional trainers (from statutory NHS, LA, and Voluntary Sector services) work with organisations interested in employing PSWs to ensure that they have a full understanding of what this means, why they are embarking on it, and whether they have the funding, structures and culture necessary.

Support is offered at organisational level, with teams where PSWs will be employed, with Learning and Development Departments and with HR departments to develop a training and development plan fit for their organisational context.

This includes support with selection and recruitment of trainees, organisation of pastoral support during training, preparation of placement mentors and delivery of a ten day training course with additional specialist modules for PSWs working in specialist placements; assessment of competency of PSWs and advice on employment support.

ImROC offers an accreditation system which examines the organisational context including training and is renewed annually following annual peer review.

9.2 Training before or after employment?

Organisations need to decide whether PSWs will be employed and then offered training, or recruited to training which enables assessment of their competency and readiness to work before they are recruited to a post.

The advantage of offering training prior to employment is that it enables the student to fully understand the nature of the role and gain experience of working as a peer support worker during a student placement; it ensures that they have the skills and understanding to keep themselves and those whom they support safe; and it offers the organisation greater confidence in the ability of the recruit to undertake the work.

Since other professional groups undertake training prior to employment it seems to make sense.

9.3 Ongoing development of PSWs

PSW training only provides the basic knowledge and skills for peer working. As with any job, most development takes place with practical experience over time, and further training is necessary to gain more advanced and/or specialist skills.

PSWs may wish to learn more about Recovery and Wellness Planning, Coaching Skills, Problem Solving, Co-Reflection, Community Development, Peer-to Peer supervision, Supporting family members, Training to be a trainer, Survivor research skills, and more.

These training needs may be identified in their personal development plan, supervision or appraisal system – (importantly all primarily based on and informed by their own experience). Whilst some of these courses will be relevant and available to all staff, others will be specific to PSWs. Organisations need to plan ways of enabling PSWs to access appropriate ongoing education – either through inhouse courses or in the Recovery College (if there is one locally) or by accessing external trainers.

There is often a period of time when organisations are building their capability in peer support and investing in the development of staff who will become peer supervisors, peer trainers, peer researchers and senior PSWs as the peer workforce expands (see HEE paper on career pathways).

9.4 Offering relevant courses to all staff

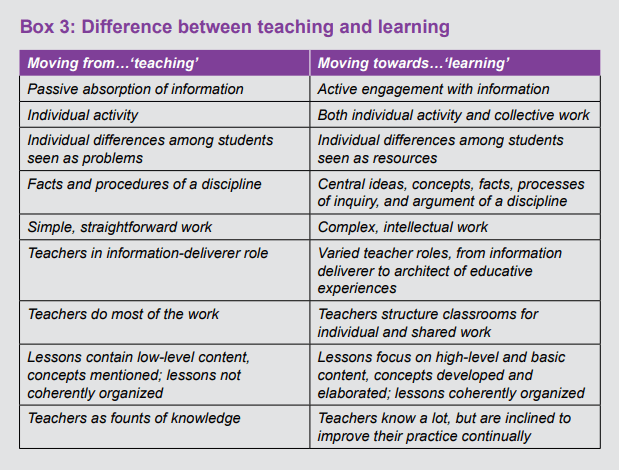

The employment of PSWs is only one way of shifting the culture of services. Organisations that employ PSWs need to ensure that all staff have access to courses that enable them to play a part in delivering more Recovery focused services. Personal Recovery and Wellness planning, shared decision making, coaching approaches, solution focused approaches, shared crisis planning, joint safety planning, collaborative care planning …. are all fundamental aspects of practice in Recovery focused services so training needs to be available for all staff to understand and implement these approaches.

Similarly, team leaders and managers need to adopt a strength based, facilitative and supportive style of management to enable all staff to work to their full potential, to build on their strengths and cope with external stressors. Everyone has the right to employment support and reasonable adjustments to their role. Training must be available for managers to learn these skills – not just when working with PSWs, but for the benefit of everyone in their service.

9.5 Non-peer staff with lived experience

As previously referenced, between 30 and 60% of staff working in mental health services have been found to have personal experience of mental health problems. Traditionally, they have been advised not to disclose their own stories.

However, Recovery focused services are all about breaking down barriers between ‘them’ and ‘us’, sharing more about ourselves, demonstrating our shared humanity.

Staff are already beginning to feel more confident about disclosing their own experiences to their colleagues and people who they support; this appears to be even more the case where PSWs are employed.

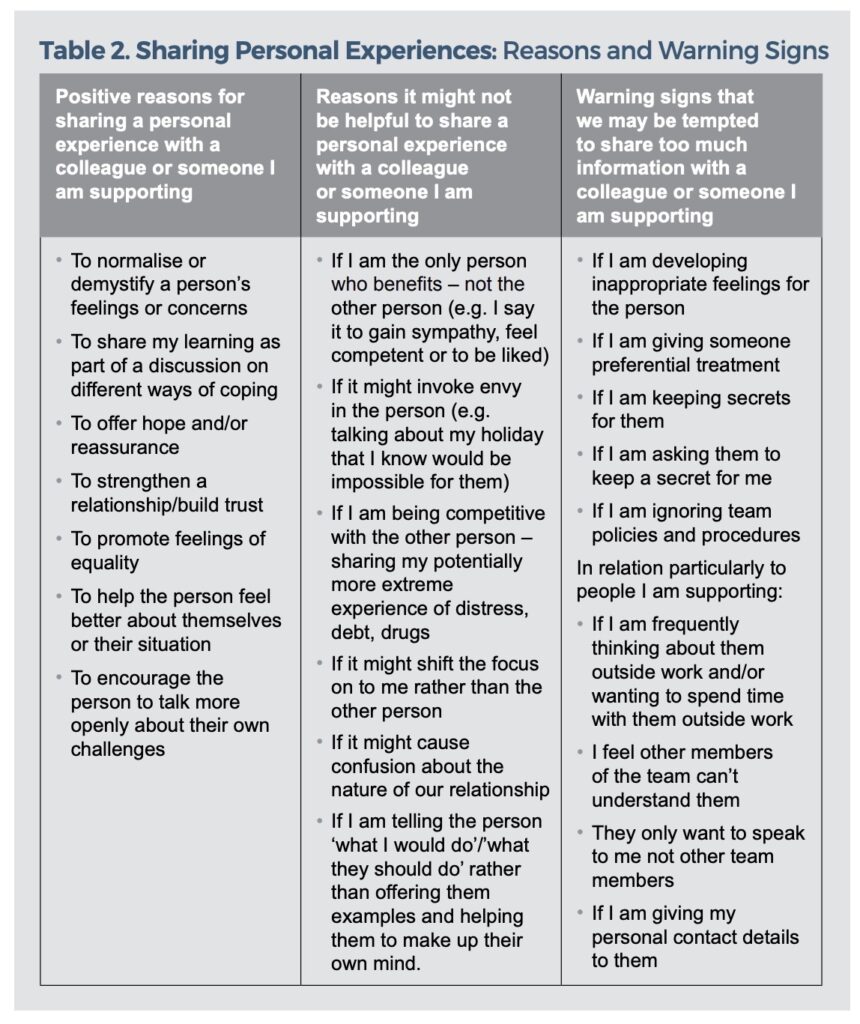

Although PSWs have received training in how, why, when and how much to share of their own stories, other staff have not. Training departments need to lead the way in ensuring that organisations have clear policies and expectations about whether, how and when all staff can safely, appropriately and effectively disclose aspects of their own life and lived experiences.

10. Supervision for peer support workers

Regular supervision is absolutely essential for all practitioners including peer support workers. The CQC defines supervision as “a safe and confidential environment for staff to reflect on and discuss their work and their personal and professional responses to their work. The focus is on supporting staff in their personal and professional development and in reflecting on their own practice” (CQC 2013)

The challenge for organisations employing PSWs is to consider what supervision means for a profession that is based on personal experiential knowledge and experience rather than a recognised theoretical and professional knowledge base.

Leaders in the field of peer support in the US have defined peer supervision in some detail. Sherry Mead (the author of Intentional Peer Support (IPS) draws on the principles of peer support in describing supervision as a process of co reflection where the supervisor and supervisee help each other to reflect on their practice, where expertise is created together through a process of learning, practicing and reflecting.

She describes this co reflection approach as “referring to reciprocal arrangements in which peers work together for mutual benefit where development feedback is emphasised and self directed learning and evaluation is encouraged” (Mead 2012)

Lori Ashcraft, the originator of peer specialists in Recovery Innovations Arizona, describes peer support supervision as “a strengthsbased process that supports the role of peer specialist. Feedback is important, promotes trust in the relationship, and supports professional development. All supervision must occur within the framework of existing human resource standards and procedures” (Ashcraft, L 2015)

10.1 Why focus on supervision for peer workers?

Peer roles are unique. There is no other occupation in the NHS that requires postholders to share aspects of their personal experiences and it is this that makes supervision both essential and distinct in the following ways:

- Working with people who disclose personal experiences of trauma and mental health challenge is demanding for everyone. For people with their own lived experience it can trigger distress, lead to reliving traumatic events and even lead to vicarious trauma.

- Recalling and referring to personal experience of trauma, mental health problems and Recovery in itself is demanding emotional labour

- Open acknowledgement of personal experience of mental health challenges has the potential to render PSWs vulnerable to discrimination by other staff

- Reference to personal experience is a huge strength and asset in relationships with people using services and can lead to closer connections, greater trust, more disclosure and higher/different expectations from clients.

This brings with it continual questions for each peer about relational boundaries with the individual (e.g. what is the difference between peer support and friendship?) and with the team (what parts of the story I have been told should be shared with the team?); about their own role (I feel more connected to the views of this individual than with other staff … what do I do about this?; I do not feel comfortable with the language used to describe this behaviour…).

Skilful supervision can support PSWs to maintain quality, integrity and safety of peer practice; provide coaching/problem solving to address challenges in practice, develop personal practice and repertoire; enable safe and appropriate sharing of emotional burden of the role; help them to integrate within their workplace, and provide a forum to raise concerns about organisational policies and practice and share decisions about next steps.

10.2 What sort of supervision do PSWs require?

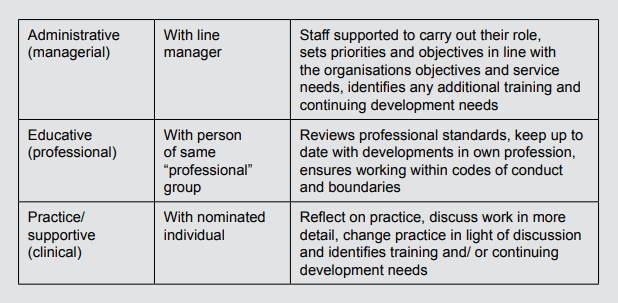

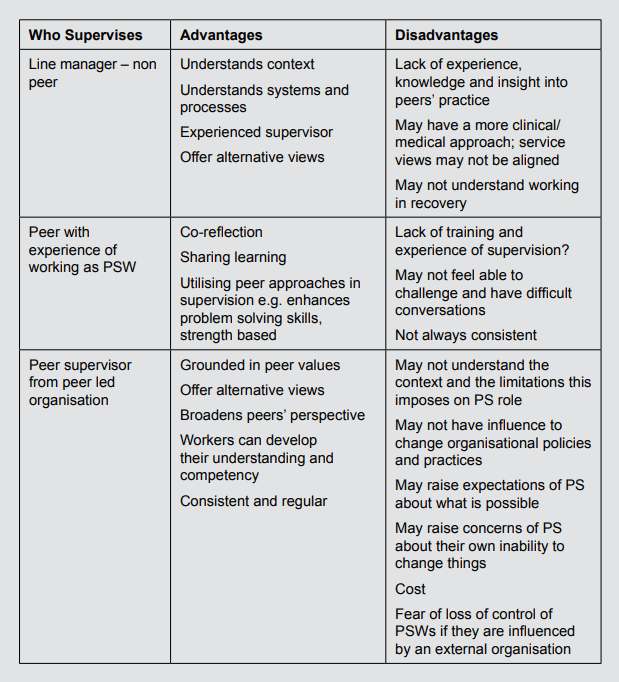

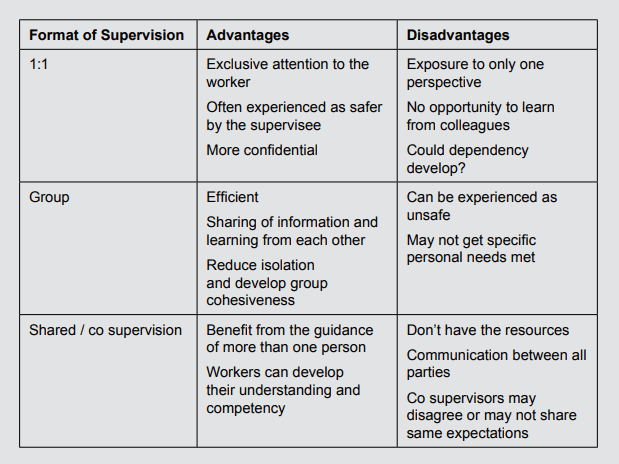

Much of the literature that describes supervision required in the NHS describes three types: managerial, professional and clinical. Within the context of peer working these headings could translate into administrative, educative and practice or supportive supervision. Arguably these headings are better as they describe the “type” of supervision they can expect.

Traditionally supervision models fall into three categories: developmental, integrated and orientation specific. All of these have relevance for the supervision of PSWs, but PSW supervision requires consideration of an additional category which defines whether the supervisor has their own lived experience and expertise in peer support.

Developmental supervision refers to the different stages of a supervisee’s development from “novice to expert”. Each stage consists of discrete characteristics and skills; the key is for the supervisor to accurately identify the supervisee’s current stage, and offer feedback and support appropriate to that level alongside facilitating the supervisee’s progression.

The model uses a process of “scaffolding” to encourage the supervisee to use prior knowledge to produce new learning which fosters the development of critical thinking skills. The Integrated Development Model is by far the most researched development model. For more detail please see Stoltenburg (1981), Stoltenburg & Delworth (1987) and finally Stoltenburg, McNeil & Delworth (1998).

Integrated Supervision relies on more than one theory or technique in much the same way as clinicians describe their practice as eclectic; that is, integrating several theories into consistent practice. One well-recognised model is Bernard’s Discrimination Model originally published 1979.

This model comprises three areas of focus (intervention, conceptualisation and personalisation) and three supervisory roles (teacher, counsellor and consultant). What this means in practice is that the supervisor can respond in one of nine ways. For example, the supervisor can respond as teacher, while focussing on specific intervention; or respond as counsellor whilst focussing on intervention and so on.

Orientation specific supervision model adopts a “brand” of therapy that is selected based on an analysis of the supervisee’s role (for example, CBT informed supervision for a CBT practitioner). Within peer support, Mead’s co-reflection based on principles of mutual support and reciprocity is closest to a brand specific type of supervision for peer support.