Using peer support workers to support the recovery of people with mental illness can add significant value to mental health services, sometimes at no extra cost, according to new research published today.

This paper sets out the spectrum for peer support in mental health services, which can range from naturally occurring through to formal employment of people with lived experience of mental ill-health.

5. Peer Support Workers: Theory and Practice

Julie Repper with contributions from Becky Aldridge, Sharon Gilfoyle, Steve Gillard, Rachel Perkins and Jane Rennison

INTRODUCTION

Peer support is “offering and receiving help, based on shared understanding, respect and mutual empowerment between people in similar situations”. In this paper we will examine the concepts and principles of peer support and present examples from organisations which now have peers in their workforce.

The ImROC programme has recommended the use of peer workers to drive recovery-focused organisational change. ImROC recognises the value of a range of different roles for peers in all types of mental health services. Whether they are paid or voluntary, working in public, private or independent services, peer workers have a valuable role to play.

We have concentrated on the contribution of peers working inside mental health services because of the multiple benefits that they can bring. Working together, ‘co-producing’ services alongside traditional mental health professionals, they can offer a truly comprehensive and integrated model of care.

We also have to be concerned with maximising ‘value for money’ and we believe that peers – properly selected, trained and supported – can improve the quality of services at no extra cost, possibly even with cost reductions. This would put the voice of those with lived experience truly at the centre of mental health services – which is where it belongs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

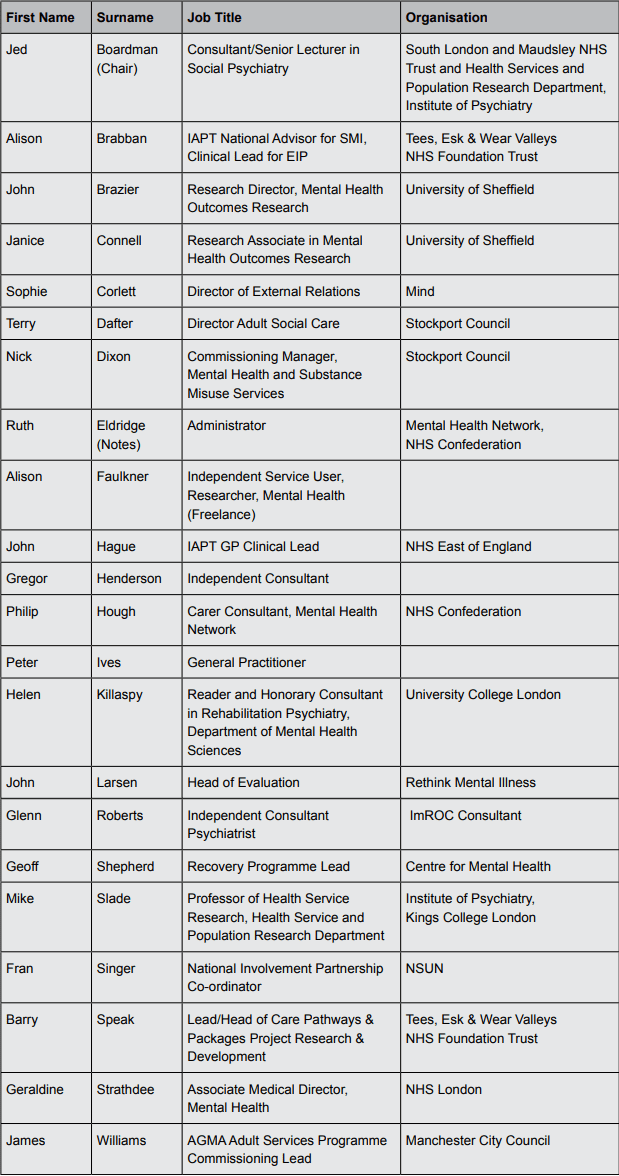

Advances in recovery-focused practice arise from collaborative partnerships between individuals and organisations. The ImROC briefing papers draw upon this work. Each paper in the series has been written by those members of the project team best placed to lead on the topic, together with contributions from other experts. In this case, we particularly wish to acknowledge the contribution of those whose work on the theory and practice of peer support has led the field and inspired others. They are listed on the front cover. Without these pioneers, and others like them, we would have nothing to write about. In order to illustrate many of the points in this paper, we will use quotes from the Nottingham peer support worker project, Final report for Closing the Gap, The Health Foundation, (2012).

BACKGROUND

Increasing numbers of mental health services are developing peer worker roles and are faced with similar questions and challenges. As a result, a number of reports and recommendations have appeared over the last few years (Davidson et al., 2012; Faulkner & Kalathil, 2012; Mead et al., 2001; Mental Health Foundation, 2012). We want to try to bring together the collective learning from these publications, to examine some of the basic concepts and principles underlying the practice of peer support workers in mental health services and present them together with illustrative examples from organisations who have begun to train and employ peers as part of their workforce. This paper is accompanied by a second publication (‘Developing peer support workers in your organisation’, in preparation) which will cover the practical details of implementation in more depth.

For as long as people have used mental health services they have provided each other with friendship, shared coping strategies and supported each other through dark times (Davidson et al., 2012). As the value of such mutual relationships have been recognised, so more formal peer roles have been created in mental health services across the western world. In the United States, 27 states have collaborated to create a scoping and guidance document for peer support (Daniels et al., 2010). Peer workers have also been employed in various different roles and settings in Australia (Franke et al., 2010), New Zealand (Scott et al., 2011) and various parts of Europe (Castelein et al., 2008). In the UK, peer support has long played a central role in voluntary sector and user-led services/groups (Scottish Recovery Network, 2011; Faulkner & Kalathil, 2012; Mental Health Foundation, 2012) but peer worker roles in statutory services have been slower to establish. The ImROC programme has specifically recommended the development of peer worker posts as a driver of recovery-focused organisational change (see Challenge 8 in Shepherd et al. 2010) and the growth of peer support of all kinds appears to have accelerated supported by a number of organisations. Prior to 2010, it would have been difficult to find a single peer support worker employed in mental health services in England, but in 2013 Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust employs 25 peer support workers, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust employs 32; Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust employs 12. Many other trusts employ peers as trainers, in volunteer, bank and mentoring posts.

ImROC recognises the value of a range of different roles for peers in all types of mental health services. Whether they are paid or voluntary, working in public, private or independent services, peer workers have a valuable role to play. This is recognised in policy documents in England, Scotland and Wales. For example, in England the Department of Health papers on Health, Social Care and Volunteering all recognise the role that peer support can play in providing support, facilitating self-management, aiding prevention, improving public health and reducing health inequalities. They recognise the value of community based “peer support services, user-led self-help groups, mentoring and befriending, and time-banking schemes, which enable service users to be both providers and recipients of support” (DH, 2011, p.32) and recommend peer support as one of the “roles of mental health organisations in implementing the mental health strategy” (DH, 2012, p.51). The Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health also recommends the employment of peer mentors and patient experts to work on ‘self-management, advocacy, training and mentorship programmes in order to improve personal understanding and responsibility for wellbeing’ (JCPMH, 2012, p.9). The recent Schizophrenia Commission (2012, p.35) specifically recommends that “all mental health providers should review opportunities to develop specific roles for peer workers”.

WHAT IS PEER SUPPORT?

Peer support may be defined simply as “offering and receiving help, based on shared understanding, respect and mutual empowerment between people in similar situations” (Mead et al., 2001). Thus, it occurs when people share common concerns and draw on their own experiences to offer emotional and practical support to help each other move forwards. This is well articulated by peer support workers from Nottingham.

“…They know I’m not the expert, they know we’re just us, both trying to beat the same demons, and we’re trying to work things through together…. I said to her, ‘I’ve got my own experience of mental illness, I’ve been on the ward myself and so on,’ and with that she sort of jumped up and gave me this huge hug.”

Peer support encompasses a personal understanding of the frustrations experienced with the mental health system and serves to reframe recovery as making sense of what has happened and moving on, rather than identifying and eradicating symptoms and dysfunction (Bradstreet, 2006; Adams & Leitner, 2008). It is through this trusting relationship, which offers companionship, empathy and empowerment, that feelings of isolation and rejection can be replaced with hope, a sense of agency and belief in personal control.

“I wanted to be able to show people that however low you go down, there is a way up, and there is a way out… The thing I try to install is, no matter where you are, if you want to get somewhere else you can, there’s always a route to get to where you want to be.”

The shared experiences of peers in mental health settings are most commonly their mutual experiences of distress and surviving trauma. However, it is not always enough simply to share experiences related to mental health. Support is often most helpful if both parties have other things in common such as cultural background, religion, age, gender and personal values (Faulkner & Kalathil, 2012). For people who have experienced marginalisation and exclusion (such as those from minority ethnic groups) it can be important for the support to come from someone who shares these experiences of oppression and/or of facing structural barriers so that they can ‘speak the same language’.

Relationships with others who share your experience are unlikely to be helpful if they are overly prescriptive, burdensome, or felt to be unsafe (in terms of trust and confidentiality). The peers from user-led groups interviewed by Faulkner and Kalathil (2012) also found that relationships were more supportive if both people were willing both to provide and receive support and had gained some distance from their own situation so that they were able to help each other think through solutions, rather than simply give advice based on their own experiences. For these reasons, training, supervision and support are all essential for peer workers employed in services.

DIFFERENT FORMS OF PEER SUPPORT

We can draw distinctions between three broad types of peer support: (a) ‘informal’ (naturally occurring) support; (b) peers participating in consumer, or peer-run, programmes alongside formal mental health services; and (c) employing people with lived experience within statutory services, irrespective of whether they are employed by the statutory organisation or by independent sector agencies.

These different forms of peer support also vary along a number of (not necessarily linear) dimensions. These include: the number of people involved, the level of choice involved, the rules governing the relationship, and the extent to which peers are at the same stage in their journey of recovery. These dimensions are summarised in Box 1.

Box 1: Dimensions of peer support

- Group vs. individual: Some forms of peer support, like peer run support groups and courses, offer only group support, although members may form individual relationships as a result of meeting through the group. Other forms, like informal friendships, buddy systems, co-counselling or individual interactions between peer workers (paid or unpaid) in services, provide more individualised support.

- Extent to which both parties choose to enter the relationship: Informal networks and friendships are entirely elective. Someone joining an existing group, or enrolling on a self-management course chooses to do so, but does not have choice over the other participants or the peer trainers. Someone entering a hostel, crisis or day service (whether user-led or not) may have some degree of choice about whether they enter the service and about the workers (paid or unpaid) with whom they engage, but the individuals using the service have little choice over who is employed there (although peers may be involved in staff selection).

- The ways in which rules govern the relationship: No relationships are entirely without rules or boundaries. Sometimes these are implicit, as in ordinary friendships while others are more explicitly stated, as in codes of conduct, for example in buddy and befriending arrangements. The most formal ‘rules’ are those contained in Job Descriptions which are usually set in a number of other regulations which govern employees of the organisation. Ethical guidelines differ in a similar fashion. In informal friendships they are implicit; in other relationships (e.g. peer support groups) they may be agreed by consensus or, again, formalised in codes of conduct for employment. These formal rules apply to all paid staff.

- Extent to which the parties involved are in the same place in their recovery journey: Everyone’s recovery journey is different and each journey is usually far from linear. At different points in time one person may be further on, but then they experience a setback so reversing roles. Often in peer support groups there is a facilitator or organiser who may, at the time of fulfilling this role, have moved further in overcoming the challenges than those who are new to the group. Similarly, it might be assumed that peer trainers in self-management courses or paid workers in services will have moved beyond their most recent experience. Clearly these roles can change over time, but peer workers may experience setbacks and people currently attending services can and do move on to the role of trainers, co-ordinators and workers. Such is the dynamic nature of peer support.

DIFFERENT ROLES

There are many different ways in which peer workers can be employed within mental health services.

They may work in dedicated teams:

- responding to referrals for peer support from other teams (Repper & Watson, 2012)

- working across ‘transitions’, e.g. from specialist community teams to Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs), or from inpatient wards to CMHT

- providing specialist consultancy advice regarding recovery-focussed practices such as WRAP (Wellbeing Recovery Action Plan), or other forms of Personal Recovery Planning

- providing service-wide functions, e.g. speaking at staff induction, reviewing policy documents, undertaking quality assurance exercises, providing mentorship for staff, etc.

Alternatively, they may be employed in addition to staff in existing teams (inpatient or community) to bring a specific focus on the needs of service users:

- Facilitating earlier discharge from inpatient wards, working across boundaries to engage with inpatients prior to discharge, spend time planning for life in the community and then supporting people after discharge by home visits, meetings with friends and community contacts, etc.

- Leading on personal recovery planning, using their own experience to help the person identify and prioritise goals, develop understanding, control and selfmanagement strategies and to ensure that all of this is communicated to the professional staff team.

- Improving the value of follow-up appointments (e.g. outpatient consultations) helping the service user think through questions and concerns prior to appointments and how best to convey these to professionals. This can specifically help to establish the culture of ‘shared decision making’ (e.g. regarding medication management).

- Supporting learning in Recovery Colleges (Perkins et al., 2012) working with staff to co-produce and co-deliver courses and facilitate productive engagement.

- Leading on social inclusion. As already indicated, peer workers often come from the same physical and cultural communities as the people they are supporting. They are therefore particularly well-placed to identify appropriate community resources and activities and to facilitate engagement by accompanying their peers until they are confident and comfortable to attend alone.

As will be evident from the above, the peer support role as an adjunct to existing staff roles has considerable overlap with nonpeer support roles (e.g. Support, time and recovery ‘STR’ workers) and with peer advocacy. The difference is that peer support workers are specifically employed to use their personal experience to support others. But they cannot be expected to achieve this if they are left to work alone. In Recovery Innovations in the U.S. over half the mental health workers employed by the service are trained peers (See META Services Arizona in Shepherd, Boardman & Slade, 2008); and in Nottinghamshire the aim is for at least two peer workers in every team (see Nottinghamshire Healthcare Trust Recovery Strategy 2009-12, 2013-16). Some examples of peer worker roles are given in Box 2.

Box 2: Examples of specialist peer worker roles

Nottinghamshire Partnership Mental Health Intensive Care Unit (MHICU): The team leader had one ‘Band 3’ vacancy and was keen to bring lived experience into the team to promote a more recovery-focused ethos. The post was therefore converted to a peer healthcare assistant and three part time peers were recruited. They had all previously spent time in inpatient settings. The staff team spent a whole day learning about peer support, expressing their hopes and fears, generating ideas about how the peers might best use their experiences. Three months later all the peers say they are very happy working at the unit and feel they can make every aspect of their work recovery-focused whether it is serving meals, escorting patients or simply talking to them. They feel able to talk about their own experiences when appropriate and have day-to-day support from the team leader who encourages them to bring their insights and ideas to all team meetings.

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust – Integrated Offender Management (IOM) Peer Workers: In May 2012, CPFT appointed 5 peer workers to their IOM teams based in Peterborough, Cambridge and Huntingdon police stations. The role was very new and a lot of work was done to ensure that the peers worked out their roles in relation to the nurses also employed by the Trust in the IOM teams and with the police and probation staff who form the main staff groups. The peers are working in partnership with the trained nurses on the recovery needs of prolific offenders with mental health problems. They work with a number of external organisations, including drug and alcohol services, housing and adult education and have a particular role in training staff from other agencies (e.g. police) in relation to mental health issues. Due to the nature of the new role, a higher banding was required so that the peer workers could be more autonomous.

THE CORE PRINCIPLES

Whatever the form of peer support or the nature of the role, there are a number of core principles that peer support workers should aim to maintain. These are summarised in Box 3. They include: mutuality, reciprocity, a ‘non-directive’ approach, being recovery-focused, strengths-based, inclusive, progressive and safe. These principles can be used to guide training and supervision and to maintain the integrity of the peer role wherever they are located and whoever employs them (see below).

Box 3: The core principles of peer support

1. Mutual. The experience of peers who give and gain support is never identical. However, peer workers in mental health settings share some of the experiences of the people they work with. They have an understanding of common mental health challenges, the meaning of being defined as a ‘mental patient’ in our society and the confusion, loneliness, fear and hopelessness that can ensue.

2. Reciprocal. Traditional relationships between mental health professionals and the people they support are founded on the assumption of an expert (professional) and a non-expert (patient/client). Peer relationships involve no claims to such special expertise, but a sharing and exploration of different world views and the generation of solutions together.

3. Non-directive. Because of their claims to special knowledge, mental health professionals often prescribe the ‘best’ course of action for those whom they serve. Peer support is not about introducing another set of experts to offer prescriptions based on their experience, e.g. “You should try this because it worked for me”. Instead, they help people to recognise their own resources and seek their own solutions. “Peer support is about being an expert in not being an expert and that takes a lot of expertise.” (Recovery Innovations training materials. For details see www.recoveryinnovations.org)

4. Recovery-focused. Peer support engages in recovery-focused relationships by:

- inspiring HOPE: they are in a position to say ‘I know you can do it’ and to help generate personal belief, energy and commitment with the person they are supporting

- supporting people to take back CONTROL of their personal challenges and define their own destiny

- facilitating access to OPPORTUNITIES that the person values, enabling them to participate in roles, relationships and activities in the communities of their choice.

5. Strengths-based. Peer support involves a relationship where the person providing support is not afraid of being with someone in their distress. But it is also about seeing within that distress the seeds of possibility and creating a fertile ground for those seeds to grow. It explores what a person has gained from their experience, seeks out their qualities and assets, identifies hidden achievements and celebrates what may seem like the smallest steps forward.

6. Inclusive. Being a ‘peer’ is not just about having experienced mental health challenges, it is also about understanding the meaning of such experiences within the communities of which the person is a part. This can be critical among those who feel marginalised and misunderstood by traditional services. Someone who knows the language, values and nuances of those communities obviously has a better understanding of the resources and the possibilities. This equips them to be more effective in helping others become a valued member of their community.

7. Progressive. Peer support is not a static friendship, but progressive mutual support in a shared journey of discovery. The peer is not just a ‘buddy’, but a travelling companion, with both travellers learning new skills, developing new resources and reframing challenges as opportunities for finding new solutions.

8. Safe. Supportive peer relationships involve the negotiation of what emotional safety means to both parties. This can be achieved by discovering what makes each other feel unsafe, sharing rules of confidentiality, demonstrating compassion, authenticity and a nonjudgemental attitude and acknowledging that neither has all the answers.

IMPACT OF PEER WORKERS

Although there has been relatively limited research into the effectiveness of peer support, the studies that have been published paint a positive picture of the benefits. These benefits can be considered from a number of different perspectives.

Benefits to the worker

Studies of the experiences of peer support workers report many challenges to the role which need to be identified and addressed (see below), but these are outweighed by the potential benefits. They feel empowered in their own recovery journey (Salzer & Shear, 2002) have greater confidence and selfesteem (Ratzlaff et al., 2006) and a more positive sense of identity, they feel less selfstigmatisation, have more skills, more money and feel more valued (Bracke et al., 2008). Being employed as a peer worker is generally seen as a positive and safe way to re-enter the job market and thus resume a key social role (Mowbray et al., 1998).

“I work hard to keep myself well now, I’ve got a reason to look after myself better… It’s made a real big difference to me, you know, contributing something to them. And hopefully changing their lives for the better”.

Benefits to the people being supported

“Peer workers have the time and flexibility to listen. They always take the time to talk, whereas other staff members may get called away”.

Research into the impact of peer support on the people being supported includes seven randomised controlled trials and many more observational, qualitative and naturalistic comparison studies (Davidson et al., 2012; Repper & Carter, 2010; Bradstreet, 2006). Overall, these indicate that if peer workers are well trained and supported and employed in a recovery focused service where peer to peer supervision is available, they have the potential to bring a range of benefits to those receiving support, including:

- increased self-esteem and confidence

- improved problem-solving skills

- increased sense of empowerment

- improved access to work and education

- more friends, better relationships, more confidence in social settings

- greater feelings of being accepted and understood (and liked)

- reduced self stigmatisation

- greater hopefulness about their own potential

- more positive feelings about the future.

Of course, not all studies show all these benefits and it depends a lot on how well the peer support workers are selected, trained and supported and how well the organisation is prepared. Nevertheless, the potential benefits are certainly huge and it seems that peer support workers can make a significant contribution to enhancing the experience of care (subjective quality).

In this country, an area where experience of care has consistently been shown to be very poor has been acute inpatient admission (Mind, 2012; Care Quality Commission, 2009; SCMH, 1998). Thus, it is particularly important to evaluate the effects of adding peer support workers to acute inpatient teams. In the USA, Recovery Innovations have found that, over time, the addition of trained peers can improve the subjective quality of the service, reduce coercion and the use of physical restraints (Ashcraft & Anthony, 2008). By selectively reviewing the evidence on this topic we have found that adding peer support workers to the acute pathway can also shorten lengths of admission and reduce re-admission rates leading to significant cost savings (Trachtenberg et al., 2013). This is clearly an important area for further study.

Benefits to the teams in which they work

“I just stand back and watch him work his magic. Not just with the patients who come in here so frightened and hopeless, but with staff too. He can help them see things in a completely different way.”

The introduction of peer workers is a powerful way of driving forward a recovery-focused approach within a team. Just as peer workers provide hope and inspiration for others experiencing mental health problems, they challenge negative attitudes of staff and provide an inspiration for all members of the team. Peer workers also facilitate a better understanding between the people providing the service and those using it (Repper & Watson, 2012). As this team leader said:

“Peer workers have significantly changed the recovery focus of our team, they challenge the way we talk about people from a problem and diagnosis focus to one of strengths and possibilities” (Politt et al., 2012).

Benefits to the organisation

“The values and leadership of consumers are driving the shift from a system focused on symptom reduction and custodial care to self-directed recovery built on individual strengths…” (SAMSHA 2005).

Peer workers can also use their personal experience to influence organisational policies, procedures and behaviours. The fact that they have found ways of recovering a contributing role challenges some of the beliefs that underpin the system. For example, if an organisation is to employ peer workers, then human resources departments will need to reconsider general recruitment and selection policies and the use of Criminal Records Bureau (CRB) checks. Similarly, the recruitment of peer workers may highlight the need for occupational health procedures to be strengthened in relation to staff with health work problems arising from mental health issues. Thus, processes for supporting staff and improving wellbeing may be improved not just for peers, but for the whole workforce (Perkins, Rinaldi & Hardisty, 2010).

Where peer workers are active in decision-making bodies throughout the organisation they can challenge negative assumptions, counter risk-aversive behaviour and point out discriminating language and excluding practices. Finally, peer workers stand as a living testimony to the potential of everyone with mental health problems to recover and to contribute in a significant way to the services they receive. They demonstrate the role that services can play in this if they can make the right opportunities available. The employment of peer workers in itself therefore drives change towards more recovery-focused organisations.

MAINTAINING INTEGRITY

The ImROC programme has been particularly concerned with the establishment of peer support workers in paid posts within formal mental health services (e.g. in the NHS and other provider organisations). This is because of the multiple benefits to this approach described above. However, this approach has also been criticised for ‘professionalising’ the peer role, with risks of over-controlling the natural and spontaneous relationship that is at the heart of the helping process (Faulkner & Kalathil, 2012). This is clearly a danger. But there is also a danger in not formalising the role. When people are employed in large, bureaucratic organisations, there are perhaps even greater dangers of the role being blurred and people being exploited as ‘cheap labour’. The trappings of formality – job descriptions, managers, individual review – thus provide safeguards as well as risks.

The most effective way of retaining the essence of peer support is to identify its core values and ensure that these are upheld through recruitment, training and supervision. Of course, formal processes do not guarantee that the role will be allowed to develop in a creative and sensitive way, but they do provide a framework within which this is possible and within which distortions – should they occur – can be clearly identified.

A number of other organisational challenges have been identified which can potentially get in the way of peer support workers being able to make their maximum contribution. These include:

- engaging managers to support and understand the role

- treating peer workers as staff colleagues, not ‘patients’

- enabling peer workers to meet organisational demands such as administration and record keeping

- ensuring that peers take appropriate responsibility for their own wellbeing

- placing peers appropriately so that they are not put in positions which are too stressful or isolated

- allowing peers to work to their full potential by utilising both lived experience and life skills

- ensuring that peers have the support, skills and confidence to challenge poor practice in an appropriate manner

- ensuring that peer workers have the training and ongoing support to disclose personal information appropriately

- supporting peers to negotiate ‘reasonable adjustments’ in the workplace so that they can work to their full potential

- ensuring that all staff have access to the same support for their personal wellbeing as peers do.

This is a daunting list, but it reminds us that although the introduction of peer support workers can have enormous benefits for organisations, but it is also difficult and complex and easy to get wrong. The key to integrity remains the commitment to our core principles: mutuality, reciprocity, non-directive, recovery-focused, person-centred, strengths-based, community-facing and safe. It is these that we must aspire to maintain.

CONCLUSIONS

We have argued strongly for the value of establishing peer support roles to promote recovery in mental health organisations. Peers bring unique experience and a unique set of skills which can be deployed across a range of settings to provide hope, inspiration and influence for staff and service users alike. Their potential contribution is now recognised by policy makers and governments across the world. The research base is also growing and confirming that peers, appropriately recruited, trained and supported can have multiple benefits, for those providing the service, for those receiving it and for the organisations themselves. There is even beginning to be some evidence that peers, working alongside traditional professionals, can be highly cost effective and reduce demands on other services. However, we have also noted that the establishment of peer support roles is not without significant difficulties and it is easy to make mistakes. How can some of the practical difficulties of establishing peer support workers be addressed? This is the topic for the next paper, to be published this summer.

REFERENCES

Adams, A. L. & Leitner, L. M. (2008) Breaking out of the mainstream: The evolution of peer support alternatives to the Mental Health System. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(3), 146-162.

Ashcroft, L. & Anthony, W. (2008) Eliminating Seclusion and Restraint in Recovery-Oriented Crisis Services. Psychiatric Services, 59, 1198- 1202.

Bracke, P., Christiaens, W. & Verhaeghe, M. (2008) Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy, and the Balance of Peer Support Among Persons With Chronic Mental Health Problems. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(2), pp.436-459.

Bradstreet, S. (2006) Harnessing the ‘lived experience’. Formalising peer support approaches to promote recovery. Mental Health Review, 11, 2-6.

Care Quality Commission (2009) Mental health acute inpatient services survey. Available from: http://archive.cqc.org.uk/aboutcqc/howwedoit/involvingpeoplewhouseservices/patientsurveys/mentalhealthservices.cfm

Castelein, S., Bruggeman, R. J., van Busschbach, J. T., van der Gaag, M., Stant, A. D., Knegtering, H. & Wiersma, D. (2008) The effectiveness of peer support groups in psychosis: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118, 64-72.

Daniels, A., Grant, E., Filson, N., Powell, I., Fricks, L., & Goodale, L. (2010) Pillars of Peer Support: Transforming Mental Health systems of Care through Peer Support Services. Available from: www.pillarsofpeersupport.org

Davidson, L., Bellamy, C., Guy, K. & Miller, R. (2012) Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11, 123-128.

Department of Health (2010) Putting People First: Planning together – peer support and self directed support. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (2011) No Health without Mental Health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (2012) No Health without Mental Health: Implementation Framework. London: Department of Health.

Faulkner, A. & Kalathil, K. (2012) The freedom to be, the chance to dream: Preserving user-led peer support in mental health. Together: London.

Franke, C., Paton, B. & Gassner, L.(2010) Implementing mental health peer support: a South Australian experience. Australian Journal Primary Health. 16(2):179–86.

Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health (2012) Guidance for commissioners of primary mental health care services. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Mead, S., Hilton, D. & Curtis, L. (2001) Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2), 134-141.

Mental Health Foundation (2012) Peer Support in mental health and learning disability. London: Mental Health Foundation, Need 2 Know publications.

Mind (2012) Listening to Experience: An Independent Inquiry into Acute and Crisis Care. London: Mind Publications.

Mowbray, C., Moxley, D. & Colllins, M. (1998) Consumer as mental health providers: first person accounts of benefits and limitations. The Journal of Behavioural Health Services & Research, 25(4), 397-411.

Perkins, R., Rinaldi, M. & Hardisty, J. (2010) Harnessing the expertise of experience: increasing access to employment within mental health services for people who have themselves experienced mental health problems, Diversity in Health and Care; 7, 13-21

Perkins, R., Repper, J., Rinaldi, M. & Brown, H. (2012) Recovery Colleges. London: Centre for Mental Health.

Pollitt, A., Winpenney, E., Newbould, J., Celia, C., Ling, T. & Scraggs, E. (2012) Evaluation of the peer worker programme of Cambridge and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust. Rand Europe.

Ratzlaff, S., McDiarmid, D., Marty, D. & Rapp, C. (2006) ‘The Kansas consumer as provider program: measuring the effects of a supported education initiative’, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(3), 174-182.

Repper, J. & Carter, T. (2010) Using personal experience to support others with similar difficulties: A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. London: Together/University of Nottingham/NSUN.

Repper, J. & Watson, E. (2012) A year of peer support in Nottingham: lessons learned. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 7(2), pp.70-78.

Salzer, M. & Shear, S. (2002) Identifying consumer-provider benefits in evaluations of consumer-delivered services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(3), 281-288.

SAMHSA (2005) Building a foundation for Recovery. A Community Education guide on Establishing Medicaid funded Peer Support Services and a Peer Trained Workforce. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (1998) Acute Problems. A survey of the Quality of Care in Acute Psychiatric Wards. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

The Schizophrenia Commission (2012) The Abandoned Illness. London: The Schizophrenia Commission.

Scott, A., Doughty, C. & Kahi, H. (2011) Peer Support Practice in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Christchurch, New Zealand: University of Canterbury.

Scottish Recovery Network (2011) Experts by Experience: Guidelines to support the development of Peer Worker roles in the mental health sector. Available at: http://www.scottishrecovery.net

Shepherd, G., Boardman, J. & Slade, M. (2008) Making Recovery a Reality. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. Shepherd, G., Boardman, J. & Burns, M. (2010) Implementing Recovery – A methodology for organisational change. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

Stroul, B. (1993) Rehabilitation in community support systems. In Flexer, R. & Solomon, P. (Eds) Psychiatric Rehabilitation in Practice. Boston: Andover Medical Publishers.

Trachtenberg, M., Parsonage, M., Shepherd, G. & Boardman, J. (2013) Peer support in mental health care: is it good value for money? London: Centre for Mental Health. In press.

University of Nottingham (unpublished) Evaluation of the Closing the Gap Peer Support Work project.

Peer support workers: theory and practice

This briefing paper has been produced for the Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change programme, a joint initiative from the Centre for Mental Health and the NHS Confederation’s Mental Health Network.

The pilot phase of ImROC ran from 2011-12 and was supported by the Department of Health, together with contributions from the participating services. The continuing work of ImROC is endorsed by the Department of Health and managed and supported by the Centre for Mental Health and Mental Health Network.

For more information on the current work of ImROC, please visit imroc.org.

ImROC, c/o Mental Health Network, NHS Confederation, 50 Broadway, London, SW1H 0DB

Tel: 020 7799 6666

imroc@nhsconfed.org

imroc.org

23. Building Community Partnerships to support people to Live Well: Creative Minds

Phil Waters – Strategic Lead for Creative Minds and Julie Repper – Director (Strategy, Innovation and Development), ImROC

Introduction

Dr Steven Michael OBE, ImROC Chair of Trustees

Throughout my career working in mental health services I have seen how helpful creative activity can be in supporting people (including myself) to stay well. These activities provide a sense of peace, creativity, purpose, achievement and connection for people who have lost confidence and a purpose and meaning in life. As CEO of South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust our mission, informed and co-produced by local people, was to help people realise their potential and live well in their own communities.

Within these communities there are so many opportunities for people to join together in local groups and facilities to make art, poetry, film, to join knitting groups, craft circles, pottery workshops, choirs and music groups. For those who seek connection through more active pursuits there are walking, climbing, sailing, sports, cultural, political and faith groups.

I was fully aware of the limitations of health services in supporting people to rebuild their lives and wanted to find a way of linking all those using mental health services with communities of their choice. The seeds of this idea germinated in my own mind to become Creative Minds.

In practice the network (or movement) has been led and supported by hundreds of local people, some of them who use services, some work in services, but with the vast majority simply doing the things they enjoy doing in their communities. This paper describes the development of Creative Minds, how it works, who is involved, what difference it makes and how others might take these community focused innovations forward in their own localities. Creative Minds is developing a package of support to organisations who wish to follow a similar route of development with contacts on the final page of this paper.

Fundamentally all of our mental health is sustained by our connections with others. The Creative Minds approach has the power to enable, engage and empower these connections.

The Power of Community

Communities are an essential part of all of our lives. They include the neighbourhoods we live in, the groups that we connect with, the activities that we engage in, the people who we relate to. They include places, people, organisations, services, groups beliefs and interests. They are mobile, agile and, as shown so remarkably during the CoVID-19 pandemic, they can come together to overcome challenges and support each other. They have knowledge, skills, time, space, ideas and assets and they are essential for us all to live well. The Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults (2019) recognises that communities are central to good mental health.

It aims ‘to enable healthcare providers and commissioners, STPs, ICSs, Primary Care Networks and people who use and have experience of services to work together to deliver a model that reinvigorates community provision and fully utilises the resources of the wider community’ with individuals ‘contributing to and participating in the communities that sustain them, to whatever extent is comfortable to them’. It recommends ‘strengthening relationships with local community groups and the VCSE to support the adoption of more rights-based care based on greater choice and engaging early with communities to address inequalities’; and ‘creating effective links with community assets to support and enable people to become more embedded within their community and to use these assets to support their mental health’.

Although the naturally occurring benefits of community engagement and development are rarely measured, there is increasing evidence of the potential that exists in communities. Pollard et al (2021, p.10) summarise the benefits of community power as:

• Improving individual health and wellbeing though people being active participants in all efforts to improve health and wellbeing.

• Strengthening community wellbeing and resilience as people are engaged in decision making and enabled (with resources and infrastructure support) to take action locally.

• Enhancing democratic participation and trust by coproducing decision making with local citizens and organisations at local level.

• Building community cohesion from the ground up by anchoring engagement and participatory approaches at a local level taking local history, strengths and challenges into account.

• Embedding and early intervention across all public services – education, transport, criminal justice as well as health and social care.

• Generating financial savings by reducing reliance on statutory services and enhancing confidence and capability at individual and community levels.

How can health and social care services work with communities for the benefit of local people?

The questions that remain for those health and social care providers that have increasingly – often inadvertently – tried to replace the role of communities through the provision of segregated spaces such as day centres or prescribe a role for communities as a step-down facility for those leaving services, is just how to support the central role of communities. How to access the power of communities and how to work collaboratively with the huge range of community assets and resources rather than exploiting, overpowering or ignoring the facilities, roles, relationships and activities that give life meaning and are central to living well. Or, as Russell summarises this challenge, how do we debunk the belief …’that institutions are the primary producers of what we need to live a good life of prosperity and well-being by repositioning and re-centring regular people and their communities and recognising them as the primary producers and contributors of those things that lead to increased well-being and health’ (Russell, 2023).

There already exist tried and tested approaches to realise or release the power of communities. ImROC has previously described the power of a local coproduction forum with local citizens, organisations and services as a means of sharing intelligence about what exists where, identifying gaps in provision and resources and fully participating in decisions about local community development. We have also demonstrated the benefits of employing peer support workers to enable people who are excluded, isolated and inactive to engage in activities, relationships and facilities of their choice; the power of social prescribing services to link people with local resources; and the impact of building competence and confidence of local communities’ resources to accommodate people with particular needs (Live Well paper 16. Developing Primary Care Networks and Community Focused Approaches: A Case Study – ImROC – Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change) (Repper et al 2019).

This paper describes a different approach to community engagement and development. One which facilitates the power and resources in local communities in order to improve opportunities for people with mental health challenges to both participate in and contribute to meaningful activities, relationships and facilities of their choice in their communities.

What is Creative Minds?

Creative Minds was set up in 2011 to support the development and delivery of creative arts, sports, recreation and leisure-based projects to improve the lives of people who use South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SWYPFT) services. Creative Minds has developed into a charity hosted by SWYPFT with over 120 community partners developing over a 1000 community-based partnership projects across the footprint covering Barnsley, Calderdale, Kirklees and Wakefield. These projects offer opportunities for people who use/ have previously used SWYPFT physical and mental health services (including Yorkshire and Humber Forensic Secure Services) and build the confidence, competence and capacity of local communities.

We know that the context in which people live their lives is the most important determinant of life expectancy, and our ambition is to make sure that every person experiencing health issues using the local NHS organisation has the opportunity to engage with meaningful activities in their community and achieve their potential. Many people readily engage with NHS services – and Creative Minds activities are complementary to the service offer. However, for people who avoid using services, reject their diagnosis, and/or disagree with a medical approach, Creative Minds offers complementary and alternative approaches in the community. By having one foot in the NHS and one foot outside, Creative Minds can get alongside individuals who use services and support them to connect with meaningful activities in their communities and neighbourhoods that help individuals to regain, hope, meaning and fulfil their potential.

Creative Minds is the broker or the bridge between the SWYPFT and the communities it serves. It seeks to remove the barriers that inhibit partnership working. Traditionally, community organisations and groups have found it difficult to work directly with the Trust due to slow decision-making processes, difficult payment systems, risk averse attitudes and a culture that may not recognise the value of creative approaches. Creative Minds’ approach is very much based on community development principles and asset-based approaches and operates more like a social movement, that empowers local communities to be part of decision making and development.

A major aim of Creative Minds is to build a strong infrastructure of community and voluntary organisations, providing communitybased activities and relationships for all those who wish to engage with them, starting with those who access NHS services in the SWYPT footprint. Creative Minds works in partnership with individuals and groups in the community to coproduce opportunities for people to engage in activities that are meaningful and fulfilling to them. It supports the development of projects through mentorship and guidance to enable them to access external and Trust funds and to enhance both inclusivity and confidence to enable people with long term condition and challenges to fully participate. The passion and commitment to creative approaches that are held by the network of external champions helped bring Creative Minds to life. Champions also work within SWYPFT to support the development of projects, allocated according to their geographical locality and their areas of interest.

Inception of Creative Minds

Creative Minds grew out of a series of workshops that brought SWYPFT service users/carers staff and community partners together to gain a broader understanding of the needs of the population served by SWYPFT. Feedback stressed that engagement in creative activity can be invaluable in recovering a meaningful life, and that this was best provided in a safe, supportive environment. Participants felt that more creative projects would be initiated – and those already in existence would become more accessible – with support to set up and get started. And individuals currently using Trust services felt they could benefit from some initial practical and emotional support to engage in activities. However, there was agreement that projects would find ways of running independently in the longer term, just as participants would gain confidence over time. The workshop feedback generated an approach in which as participants engaged in activities they could begin to imagine a different life for themselves and move from the narrow confines and definitions of life as a receiver of healthcare towards new horizons as a contributing citizen. Creative engagement was also seen as an opportunity for people to partner as equals, to shift the power imbalance between care providers and the cared for, and for people to progress towards personal autonomy through developing a creative passion.

From these workshops in 2011, the Trust committed £200,000 funding to match fund community-based projects to improve inclusion and support for people with ongoing mental and physical health conditions.

Aims, objectives and values of Creative Minds

The agreed aim of Creative Minds is to develop access and take up of creative activities to improve the wellbeing of participants by increasing their self-esteem so they feel confident to try new things, develop social skills as they meet new people and feel a new sense of purpose and confidence as they engage in activity that they find meaningful and fulfilling.

Creative Minds’ objectives are to:

• Increase participation in creative activities for people who use Trust services.

• Coproduce quality creative practice and approaches within community based organisation.

• Increase inter-agency partnerships and bring in more funding for creativity and wellbeing.

• Develop a research/evidence base regarding creative approaches in relation to health, wellbeing and living well.

The values of Creative Minds are the guiding principles of all they do. Coproduction lies at the heart of their approach, from the way they developed to the way collective decision making continues to drive project development. Co-producing creative projects adds substantial value to the Trust’s overall service offer by exploring areas beyond its current provision and co-creating new and innovative solutions to the issues faced by individuals and communities. The approach builds and uses social capital to create and restore a community spirit that enables people to reach their potential and live well in their communities, which is the Trust’s coproduced Mission. Working and delivering services in partnership has large mutual benefit for all as people learn from each other: community organisations and groups have greater awareness of mental and physical health conditions and the Trust learns more about creative approaches and how community organisations operate. Creative Minds offers more opportunities for people who use services to join activities alongside people who don’t use services as equals. This reduces discrimination self-stigmatisation and builds confidence and capabilities for all.

Staffing of Creative Minds

The Creative Minds strategy was originally developed with the Trust’s Equality and Inclusion team who facilitated coproduction workshops to agree a strategy to drive the early initiatives. As projects grew in popularity it was clear that the approach was becoming an entity in its own right and in 2015 Creative Minds became a registered charity. The Trust supported a business case to create a separate staffing structure to manage and develop Creative Minds projects and to explore the potential to expand the approach and draw down new sources of funding. At this stage an independent staffing structure was agreed including: a Strategic Lead, four Development Coordinators and Project worker to support the development of Peer Led Projects. A growing number of volunteer Champions became involved through the strategy workshops and stayed with the development and decision-making process. These Champions included people using services and staff working in teams who had a passion for creative activities and helped to build strong pathways to connect with people using services and codeliver some of the projects. These now amount to 4-500 people who have a firm connection to support the work and can be described as a social movement. Additional funding allowed for two Creative Practitioners posts and four project worker posts.

How Creative Minds supports projects

In line with the organisation’s values and Equality and Inclusion roots, processes around development and decision making have always been inclusive. Collective decision-making groups were established in each of the Trust’s localities in Barnsley, Calderdale, Kirklees and Wakefield. The collectives continue to be made up of people with lived experience, carers, Trust Staff and community representatives and they manage the locality share of the funding. Young Foundations Community Development tool (Osbourne et al, 2021) is used to support project development which builds on strengths and targets support to any area’s weakness. The collectives continually identify and respond to gaps and needs in their local community and ensure that projects are targeted on those in the greatest need. The collectives are always open to new members to ensure strong pathways are created and any barriers to a project working are quickly identified and addressed.

Case Vignette 1: Partnership with Barnsley Football Clubs’ charity Reds in the Community

Barnsley FC wanted to make the club more dementia friendly, believing that if people with dementia could keep coming to the club it would be good for their wellbeing. They also felt the club’s historical archive would make a great basis for a memory group. The response from services was, “what do Barnsley football club know about dementia” our view was ‘ quite a bit!’. Through working with the club’s charity, we brokered a meeting and we persuaded services to get involved and Creative Minds matched the funding the club had raised and the work started. The initial project was a big success working with the Trust’s memory team and since then other approaches have developed including walking football and creative writing. The creative writing and poetry from the groups is now on permanent display at the club’s main entrance and forms part of their dementia awareness raising campaign and part of making the club more friendly to people with dementia. More recently we have developed Safety Nets a health and wellbeing programme that takes young people off the CAMHS waiting list. The coaches from the club provide physical activities combined with wellbeing session from CAMHS staff, the programme on average sees a 30-40% increase in the Shorter Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale. Barnsley CAMHS said;

“We get very positive outcomes and feedback resulting from delivery of these projects, many participants reporting life changing experiences and many young people want to stay on as volunteers and are less reliant on service”

How Creative Minds supports individuals

The projects developed and delivered through partners, complement and enhance the services that people receive from the NHS and support their recovery. They also offer an alternative for people who do not engage readily with statutory services. These are often people who suffer the most in terms of health inequalities. The loneliness and social isolation that people were feeling has been compounded by Covid 19 which exacerbated the challenges and issues that people have in managing their mental and physical health and wellbeing.

Case Vignette 2: “I would have ended up on the streets” – Babur’s story

In his late teens, Babur experienced anxiety and depression which ultimately led to him to being given medication and referred into the Calderdale insight team at the Trust. Working with the team, Creative Minds developed and funded a rock-climbing scheme that people who use services could access. Babur began his rock-climbing journey here, as part of his treatment, and hasn’t looked back since! Babur is now in full-time work and completed his rock-climbing instructor training. Babur wanted to give back to the service and Creative Minds so he now volunteers for the insight team and supports Creative Minds projects, including running weekly climbing groups and other outdoor pursuits. Babur gets to share his lived experience with people that use Trust services and share his recovery story with people whose shoes he was once in. Babur’s general health and fitness is also much improved as his diet and exercise are now designed to build upper body strength so he can climb better. Babur’s story is one of hundreds of examples of how Creative Minds has worked with the Trust to improve patient experience and outcomes. You can also hear from Babur on his personal experience through this film here.

Freedom to be agile and innovative

Although Creative Minds is hosted by the NHS, it is a charity in its own right. This brings a number of benefits. First bespoke relationships with community organisations can be developed, operating in a flexible and agile manner unencumbered by some of the bureaucracy that can stymie creativity in large statutory organisations. Second, being hosted by the NHS gives more influence within the local health care system than coming from an external position would offer.

Case Vignette 3: Extending Creativity into decision making processes

A number of Creative Minds’ partners tried to work with the Trust previously and the decision-making process to achieve matched funding for a project took 3-4 months. However, the funding was only available for a 1-month period which precluded the possibility of success. Creative Minds partnership agreements allow partners to become preferred suppliers and set up a process that enabled community organisations to plan project development. Projects are also more successful with support from staff champions, who hold a big influence on changing organisational culture more positively towards creative activities. This arrangement also included using Trust budgets in more creative ways when recruitment had been difficult, leading to more creative activities being delivered on inpatient wards.

Case Vignette 4: Innovation in Action

Creative Minds have been working with Public Health in Barnsley, to develop a community accreditation scheme to enable local sports and recreation clubs to become more mental health friendly and provide a more supportive environment for people who have mental health issues. Part of the scheme is to provide the clubs with mental health awareness and Mental Health First Aid training. The initiative has been promoted with a ‘Moving Mental Health Forward’ logo that has been adopted by Barnsley Council. Creative Minds are starting to build pathways for people from secondary Mental Health Services to enable a more guided route for people might struggle to engage with the clubs. Benefits of being active

Impact of Creative Minds

Creative Minds supports the development of projects that welcome people with ongoing mental and physical health challenges. In so doing the organisation believes Creative Minds reduces loneliness, social isolation and inactivity and the associated loss of confidence, poor self-esteem and feelings of negativity. Thus, these projects serve to build emotional resilience, providing healthy boundaries, supportive peers, self-awareness, and openness to change. Increased resilience keeps people well and able to cope with life challenges, reducing the risk of them needing NHS services. Creative Minds meet people every day who recount their own positive stories so are convinced of the benefits to their approach. However there is relatively little ‘gold standard’ research evidence to demonstrate the benefits of the approach.

A new means of evaluating creative activities has been embraced. A peer-led network of Community Reporters was trained to collect stories from participants of creative activities, to evaluate creative activities and provide new insights into why participants feel these activities are important to mental health recovery and wellbeing. This new approach to evaluation was to support people to tell and share stories of their experience of using creative approaches to recovery and/ or wellbeing through Community Reporting. Community Reporting is a storytelling movement that was started in 2007 by People’s Voice Media and it uses digital tools such as portable and pocket technologies (tablets, smart phones) to support people to tell their own stories in their own ways. Central to the approach is the belief that people telling authentic stories about their own lived experience offers a valuable understanding of their lives. Participants also complete a shortened version of the Warwick & Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale and, on average, people engaging with Creative Minds demonstrate a 40% Improvement in their WemWebs score. (Give exact results).

Community Reporting has published summaries of peer led and collaborative evaluations of different Creative Minds projects https://communityreporter.net/ feature/sport-and-wellbeing-good-moodleague and https://communityreporter. net/story/soft-and-fluffy-friday-7-february2020-137pm.

These reports show how project groups establish healthy boundaries to focus on the activity, not an individual’s problems, participants share ground rules and develop social norms. Project groups increase participants confidence and their ability to make and maintain healthy relationships with their peers. It also gives them lived experience of relationships based on shared interest. Groups are a safe environment where participants can test out relationship building skills and establish social networks that support them. This creates a ‘healthy interdependence’ and begins to create and extend social networks. Participation in the creative groups raise aspirations and hope, people with higher aspirations achieve more and work to extend their abilities.

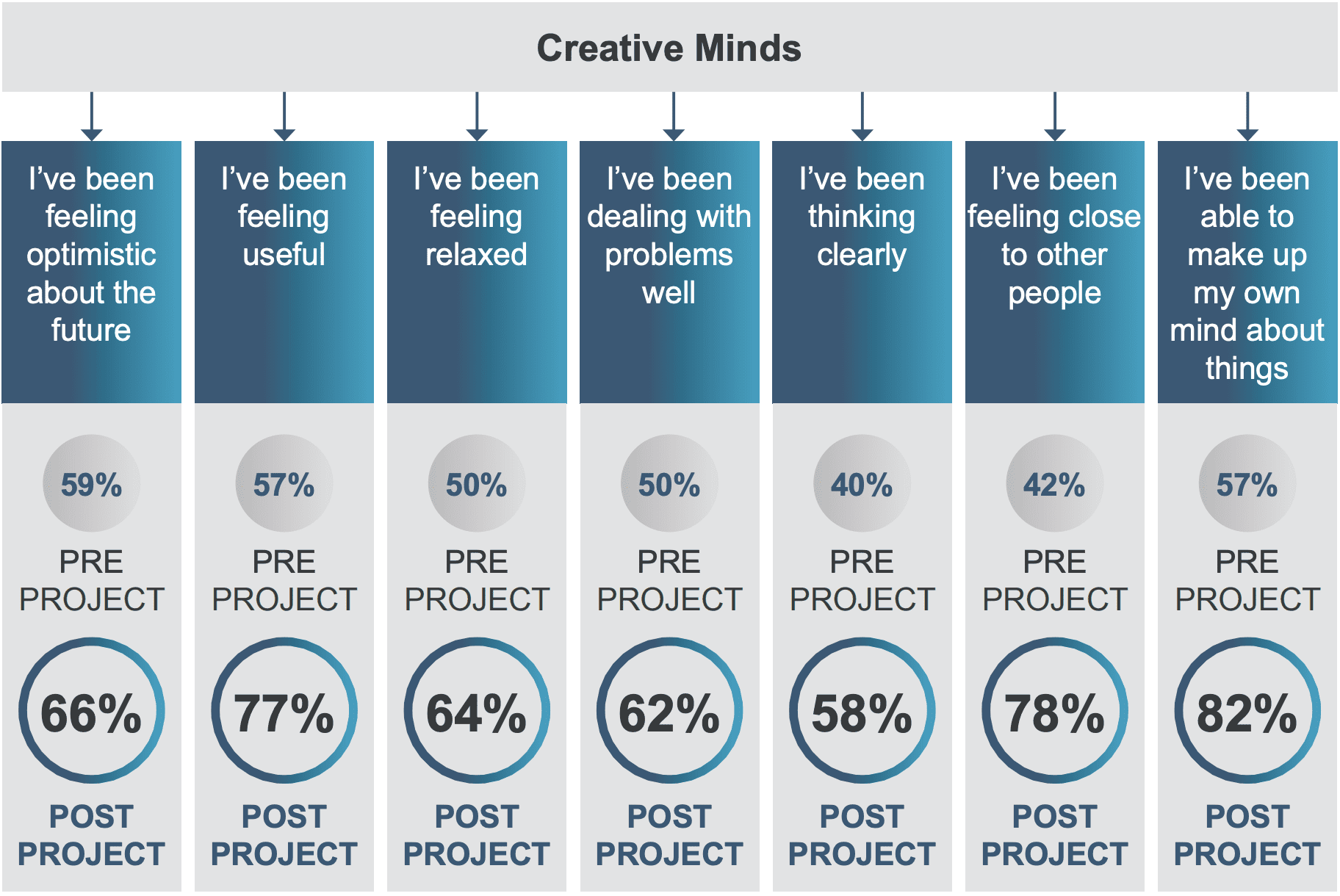

Creative Minds Evaluation Results 2017/18

Attendees of all Creative Minds projects are invited to rate their thoughts and feelings before a project commences and 3 months into the project or when it ends: (134 people completed the evaluation in 2017/18)

Attendees are asked to describe what has changed in their life since attending a project:

Peer led projects

The area of work that involves beneficiaries the most is in the peer led projects that are supported by Creative Minds. Peer led projects are a priority area for development; where participants from an existing programme who develop a passion for a particular activity can go on to develop their own groups. Together a safe process has been developed whereby peerled groups are supported to set up a simple constitution and community bank account to get started. Where possible these groups are hosted by one of the Creative Minds’ partners to give an extra level of support to get peer groups established.

What difference has Creative Minds made on culture and practice inside and outside local mental health services?

A major aim of Creative Minds was to build a strong infrastructure of community and voluntary organisations to work with to provide excellent creative projects for all who access NHS services. Therefore, to the conception and development of Creative Minds. It not only shows commitment, as an organisation, to having a creative approach to service delivery but also showcases passion for working in partnership with communities. Creative Minds has provided a way to not only build on existing good practice in NHS services, but also to work more closely with a wide range of community organisations enhancing service provision by delivering innovative, transformative and meaningful health and wellbeing projects. The passion and commitment of external champions to creative approaches has helped to bring Creative Minds to life. This infrastructure helps to embed this different way of working across all aspects of the organisation’s work.

Projects are offered that are suitable and targeted toward people who use SWYPFT services including those with a mental and or physical health diagnosis and people with a learning disability. The projects are generally open to all age groups, but there are some projects that are age and condition specific to ensure they are more suited to groups with particular needs. The group size is usually between 15-20 people, but some groups like the Art’s Café and the Good Mood Football league have up to a 100 people attending.

Within its health system, Creative Minds are creating a paradigm shift, from one that is about ‘doing to’, to one that is about creating the right conditions for individuals and collective groups and communities to do for themselves and each other. This requires a fundamental shift in power to people with lived experience and communities recognising them as equals in a relationship that creates value through meaning and hope. The principles and philosophy of Creative Minds seemed to strike a chord with many people in the NHS. It appears to have initiated a genuine social movement of which people want to be part, and for which people feel a sense of ownership.

This seems to resonate with people involved in Creative Minds and is evident from many more staff members becoming champions, but also people with lived experience wanting to get involved. This fits with theories being developed at the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement by Helen Bevan REF “The social movements perspective fundamentally challenges the ways that we have learnt to organise and lead change in the NHS. It advocates that healthcare improvement strategies need to extend beyond the topdown programme by programme approach to embrace a concept of citizen led change”

References

Bevan H (2011) Social Movement thinking: A set of ideas whose time has come? (accessed July 23)

NHSE (2019) The Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults

Osbourne, L., Wallis, E., Stumbitz, B., Lyon, F. and Vickers, I. (2021) Pathways to good work: toolkit for community organisations. Case Study. Locality.

Pollard, G., Studdert, J. and Tiratelli L. (2021) Community Power: The Evidence. London: New Local.

Russell C. Understanding ground-up community development from a practice perspective. Lifestyle Med. 2022;e269.

https://doi.org/10.1002/lim2.69 Repper, J. (2019) Briefing Paper 17. The Live Well Model: Developing Primary Care Networks and Community focused approaches. ImROC: Nottingham

Snowden, D. and Boone, M. (2007). ‘A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,’ Harvard Business Review, November 2007.

We strive to support organisations to co-produce their own pathways and training and become self-sufficient and successful in their Peer Support programmes.

ImROC provides many cost free resources to get you started in considering the multilevel preparation that might need to be considered when developing peer roles in your organisation. We know this includes:

- Recruitment, policy and HR prepared for the needs of lived experience folk

- Understanding how to run equitable recruitment, employment and development that reflects the demographic of the service reach

- Buy in from a strategic level

- Understanding of the peer role, how it thrives and what are the challenges.

- Team preparation for all teams welcoming peers

- Peer informed supervision

- A career path and progression for Peers

- Peer role descriptions reviewed for each team

- A critical mass of peers

- Designated people to run the peer programme, not just an add on

Influencing culture and practice to be more person centred and recovery focused is challenging. The ImROC team are here to offer you support to work through the unique hurdles and blocks each organisation could face.

Booking a free discovery call with one of our consultants and we can support you to explore what you might need to carry out your next steps.

Helpful Resources

Preparing for peers in organisations

The long-standing myth that mental health service providers, users and commissioners “can’t agree on what recovery is, nor offer any evidence for it” is finally laid to rest in this paper.

Supporting recovery in mental health services: quality and outcomes aims to help organisations in the mental health sector develop clear, empirically-informed statements about what constitutes high-quality services, and how these will lead to key recovery outcomes for service users. It also includes a series of recommendations for health and social care providers and commissioners, and for NHS England and the Government, that aim to support development of an evidence-based approach to commissioning mental health services.

Download 8. Supporting Recovery in Mental Health Services: Quality and Outcomes

8. Supporting Recovery in Mental Health Services: Quality and Outcomes

Geoff Shepherd, Jed Boardman, Miles Rinaldi and Glenn Roberts

INTRODUCTION

The development of mental health services which will support the recovery of those using them, their families, friends and carers is now a central theme in national and international policy (DH/HMG, 2011; Slade, 2009). In order to support these developments we need clear, empiricallyinformed statements of what constitutes high-quality services and how these will lead to key recovery outcomes. This is what the present paper aims to do.

We have had to be selective in terms of the evidence we have considered and, in many cases, we have had to make subjective judgements to come to simple recommendations. We understand that not everyone will agree with our conclusions. Nevertheless, we hope that, at the very least, they will provide a useful framework within which discussions about quality and outcome can take place at a local level in a more informed way. We therefore hope that the paper will be of value to both commissioners and providers.

A NOTE ON AUTHORSHIP

Advances in recovery-focused practice arise from new collaborative partnerships between the people who work in mental health services and the people who use them. The ImROC briefing papers draw upon this work. Where ideas are taken from published materials we cite them in the conventional form, but we also want to acknowledge the many unpublished discussions and conversations that have informed the creative development of the project as a whole over the last five years. Each paper in this series is written by those members of the project team best placed to lead on the topic, together with invited guest authors and contributions from other team members. On this occasion the authors would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Mike Slade and his colleagues in the REFOCUS group at the Institute of Psychiatry to this paper. Their careful research and generous willingness to share ideas has been invaluable to the thinking summarised here.

BACKGROUND

The ImROC programme (Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change) was established by the Department of Health in England in 2008 to help local services become more supportive of recovery for those using them and their carers (Shepherd et al., 2011). Arising from this work, we have described the basic principles of recovery (Shepherd, Boardman & Slade, 2008), presented a methodology for achieving organisational change in mental health services (Shepherd, Burns and Boardman, 2010), and described how key elements of more recovery-oriented services might be developed (Perkins et al., 2012; Alakheson & Perkins, 2012; Boardman & Friedli, 2012; Repper, 2013). Most recently, we have presented evidence for the potential cost effectiveness of services which employ formal, peer workers (Trachtenberg et al., 2013). However, we have not yet formally addressed the key issues of ‘quality’ and ‘outcomes’.

Quality indicators provide the key link between evidence-based practice and improved outcomes (McColl et al., 1998). Thus, if we can identify a set of indicators for which there is evidence that, if present in a service, they will lead to specific outcomes which support recovery then this gives us a way of assessing its quality as a ‘recoveryoriented’ service. This does not conflict with our fundamental belief that recovery belongs to the people who use mental health services and is embedded in their unique and individual lives. Judgements about ‘quality’ and ‘outcomes’ must therefore ultimately rest with them, but at the same time we recognise that clinicians and managers need information which will guide them to provide services to support recovery in the most effective and efficient ways. We recognise that this is an ambitious undertaking – quality in healthcare is always highly multi-facetted – nevertheless, we have attempted to describe a structure which will make these complicated ideas accessible to a non-specialist audience, as well as to mental health professionals, managers and commissioners.

Our primary focus has been on the experience of adults of working age using specialist mental health services. This should not be taken to imply that we are not interested in applying this thinking to services which support recovery in other groups, e.g. children, older people, those with mental health problems not in touch with specialist mental health services. Nor does our emphasis on quality and outcomes in formal services imply that we believe these are necessarily the most important sources of support for recovery. Often, these are friends, families, community groups, churches, etc. and this is evidenced repeatedly in the rich collections of life stories of people who are ‘in recovery’ (e.g. Davies et al., 2011). Their contribution should never be overlooked.

CURRENT ISSUES

As indicated above, the purpose of trying to identify valid quality indicators is to give commissioners and providers a basis for designing services that are most likely to produce certain outcomes. In the current climate this is becoming increasingly urgent as services in England struggle to categorise groups of patients with similar levels of need into different ‘clusters’ and then estimate the costs associated with effective care pathways for people who fall into these clusters. This system is known as Payment by Results (PBR) and it is intended that it will form the basis of new funding formulae for mental health services. Whether it will be successful or not is, at the moment, unclear. What is clear is that if recovery-supporting service developments are to be funded in the future, then recovery quality indicators need to be built into the care pathways in all the relevant clusters.

This in turn means that these indicators should have evidence for their association with outcomes comparable to those approaches described in the guidance for effective service provisions produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). This presents difficulties for recovery-oriented services because many of the elements are relatively new and the evidence base is therefore inherently limited (although not, as we shall see later, non-existent).

In addition to these attempts to specify quality indicators in the context of PBR cluster pathways, recent dramatic failures of care have given rise to a much greater emphasis on indicators which are not necessarily evidence-based, but reflect very basic criteria for compassionate and humane services (Francis, 2013). This renewed emphasis on the quality of supporting relationships is welcome and, as we shall see, it is highly consistent with recovery principles.

Given the complexity of the subject matter to be presented here, we have decided to take the unusual step of dividing the remainder of the paper into two. Part I contains a summary of the key indicators and recommendations for outcome measures. Part II contains a technical appendix which sets out additional detailed information to justify the quality and outcome measures recommended.

PART I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

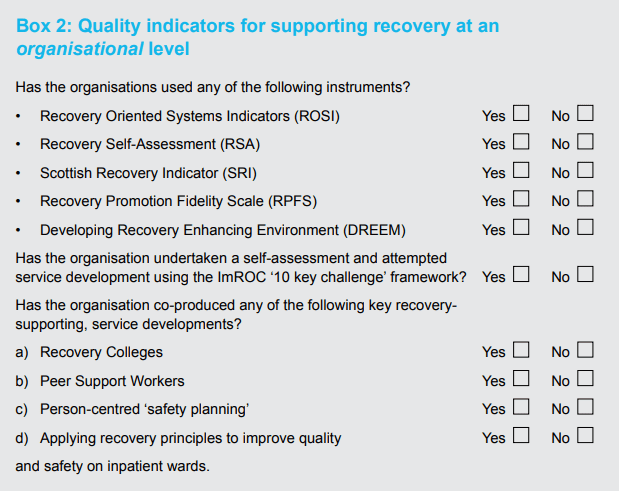

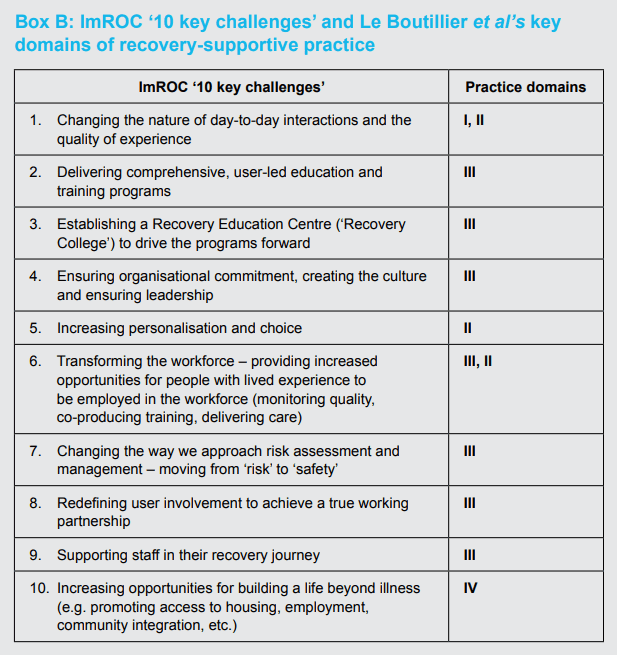

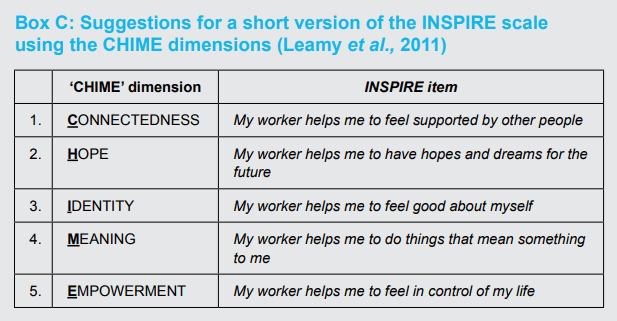

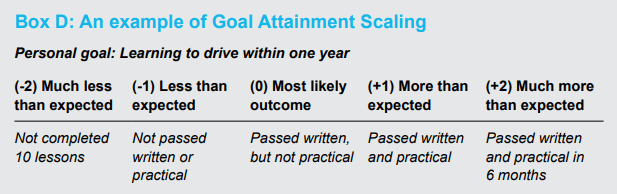

Quality indicators at an individual level