The Live Well model brings together best evidence for community development, social prescribing, health coaching, health education and volunteering – all linked and developed through a core coproduction forum. This paper describes the development and outcomes of the pioneer Live Well service – Let’s Live Well in Rushcliffe (LLWiR).

16. Developing Primary Care Networks and Community Focused Approaches: A Case Study

The Let’s Live Well in Rushcliffe Team

The ‘Live Well’ Model Report: An integrated approach to support, enable and empower people who are lonely, inactive and/or have long term conditions(s) to live well in their communities. The Let’s Live Well in Rushcliffe Team, April 2019

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to the very many people who have contributed to LLWiR.

This paper describes the model we have developed by working together as a large heterogeneous group of people with a passion for our local communities and a commitment to developing a community focused approach to support people who are isolated, inactive and / or have long term conditions.

Many of us live with ongoing health conditions or care for a family member who does; some of us offer medical services, health or social support; others work in local community services and facilities, others volunteer or are employed within the team. Some have received support from the Live Well team, others have worked on the evaluation and others have provided managerial support to the project.

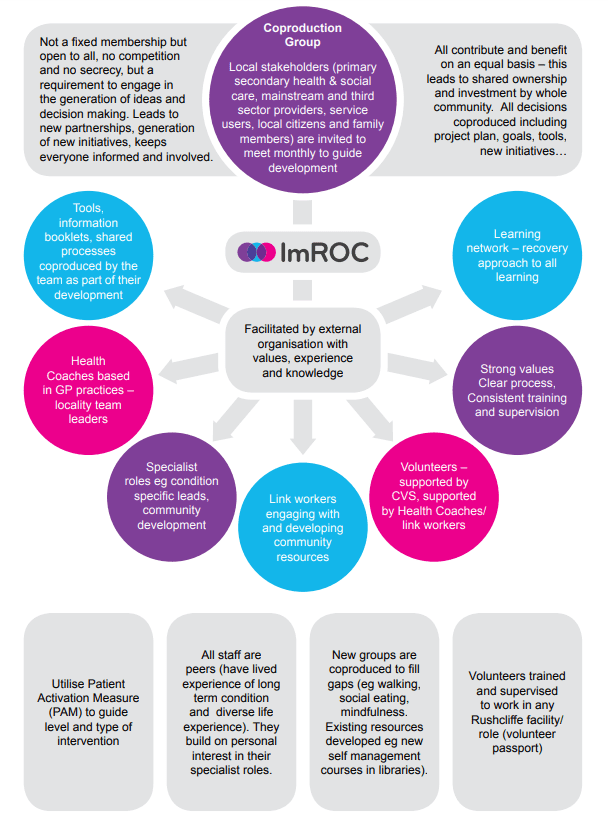

Figure 1. Key Components of the Live Well Model

1. Introduction

The Live Well model brings together best evidence for community development, social prescribing, health coaching, health education and volunteering – all linked and developed through a core coproduction forum. This paper describes the development and outcomes of the pioneer Live Well service – Let’s Live Well in Rushcliffe (LLWiR).

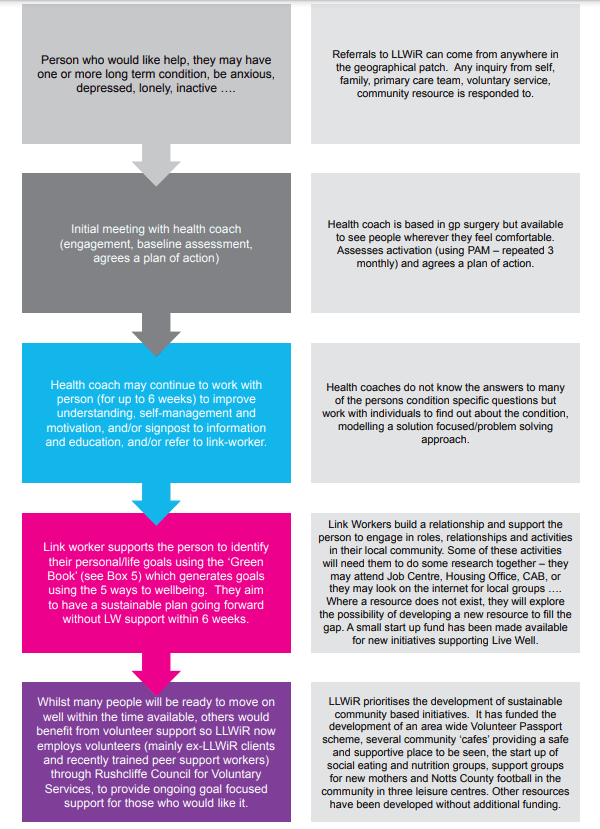

LLWiR was developed to meet the needs of people living in Rushcliffe who have complex long term physical and/or emotional health conditions and/or who are isolated, excluded and/or find services difficult to engage with. The service is open to self-referrals as well as referrals from any primary care services, social services, the voluntary sector, family members and community facilities. It offers initial engagement, assessment and health coaching based in GP practices, and where appropriate this leads on to an introduction to a link worker who supports people to engage in activities related to their personal goals and works with community resources to extend and develop opportunities in the community.

The coproduction group is the core of the project. Regular meetings with a large group of stakeholders not only co-constructed the initial model, but facilitates an ever expanding range of additional initiatives including a learning network offering educational opportunities in a range of facilities, multiple community cafes (where people can meet others in a safe place, attend learning opportunities and buy refreshments); a volunteer pathway and strong links into existing services. Additional features of the model include the provision of a small funding resource for new initiatives; employment of peers (people with their own experience of long term conditions) in all roles within the team; and external facilitation and project management from a Recovery focused organisational development organisation (ImROC).

A full evaluation of the project was undertaken by Nottingham Trent university to assess impact on health and service use. 1483 referrals were received in the first 13 months of service provision . This study reported significant improvements in patients’ physical and mental wellbeing after the initial four month period which were maintained after eight months. There was also an increase in community group membership at 4 months which reduced slightly by 8 months. There was a decrease in both primary and secondary care usage over the evaluation period. The economic evaluation of the programme attached savings to the improvements in health as well as the changes in health and social care usage. Projected over a year post-baseline assessment, this estimates a ROI of £1.00. In other words, if the patient benefits recorded for the first four months are continued for the rest of the year, the programme will recoup 100% of its costs by January 2020.

“Well, most of a population’s health and wellbeing is determined by environmental factors, and things that are not to do with healthcare. And, you know, sometimes the traditional medical model, if you like, has been very, you know, our role is to just do the medicine and that’s it. But we work in a system, we work in… All these things are interdependent, and if we want to, we might not be the experts on it, but if we want to help our patients more and help the population, then we need to access these sort of broader things”.

GP

“I think social prescribing is having the time to explore an individual’s needs regarding their wellbeing and then tailoring support to the individual’s needs, rather than just saying, ‘You can go to X, Y or Z’. Not assuming that just because somebody has a diagnosis of X that they’ll need X, but really exploring an individual’s needs and seeing and supporting the individual to achieve those goals while promoting self-management. There is no point providing a wonderful service and then, when we go, the person is back at square one”

Health Coach

I think as we work with individuals to get them engaged more with the community, the community itself then benefits by having more people engaged with it, so it becomes almost organic and it can grow and develop itself, just to help to meet the needs of its members, I guess.

Link Worker

“… theory’s all very well, but I see the patients I’m referring coming to see me less. I can have a look at their notes and see what’s been written and see that they’re making connections”.

GP

The health coach and the patient, we work together to assess a way forward, essentially looking, in very broad terms, at goals and areas for goals to be placed in. This could be over one, two or three sessions, there’s no time limit on it [lines omitted] the end result is to come up with goals and then to break those goals down into achievable steps. If that needs some support in the community, in terms of physical support to help them get to a new group, for example, or to help look at the way they shop differently or something like that, then we have link workers.

Health Coach

2. The Context

2.1 The National Context

The pressures on todays’ health and social care system are well documented: life expectancy is increasing and numbers of people living with long term conditions now account for 70% of the healthcare budget; there is a widening gap in health inequalities largely due to social factors (like finances, education, housing and isolation) – issues which are not routinely addressed by health services; public expectations of services are rising and new treatments are continually developing, placing ever greater economic pressures on services.

Solutions to this complex picture have been proposed in the 5 year forward view1 and further detail is provided in the 5 year forward view for mental health2 and the GP forward view3. All of these documents place an emphasis on primary prevention through public health initiatives; secondary prevention through primary and secondary health care and self-management as people are further enabled to manage their own wellbeing through education, coaching and personal budgets. In addition these visions for a healthier future call for greater integration of primary and secondary services – including acute and urgent care; health and social care, mental health and physical health services, and far stronger partnerships between statutory services and the voluntary sector alongside the development of more confident, capable communities.

Many new structures and approaches are developing to support the transformation of health and social care services, for example Multi-speciality Community Providers that integrate expertise in one place based team; HiAP (Health in All Policies) informed by the Marmot review4, with localities seeking to reduce Health Inequalities by actively addressing the health implications of all developments in a community: transport, industry, housing, environmental issues, education etc. Vanguard sites to lead innovative new developments in health and social care with dedicated funding for pilot projects; Sustainable Transformation Plans, recently replaced by Integrated Care Systems working across systems in an area based approach to integrate and synthesise services and sectors to meet the needs of the local population. Yet the simultaneous development of integrated approaches, alongside the generation of evidence to demonstrate their effectiveness and efficiency, whilst ‘the aeroplane is in flight’ – continuing to provide treatment and care for the local population -is a huge ask for even the most motivated and well-resourced teams.

2.2 The Local Context

When NHS England published ‘Next Steps on the Five Year Forward View’5 it signalled the intention to move to Accountable Care Systems (ACS) in the NHS. NHSE describes a key duty of an ACS to: “Deploy (or partner with third party experts to access) rigorous and validated population health management capabilities that improve prevention, enhance patient activation and supported self- management for long term conditions, manage avoidable demand, and reduce unwarranted variation ….”. Nottinghamshire (specifically the Greater Notts STP) has been identified as an area that will adopt this way of working in the first wave.

Principia is a key element of the Greater Notts STP situated in Rushcliffe, a rural and suburban area to the south East of Nottingham city with a population of 125,0766. Although the proportion of the population aged over 65 years in Rushcliffe is 15% higher than the average in England, the CCG area has the least deprived population in Nottinghamshire. In terms of its Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score, Rushcliffe (with a score of 8) is also better than the England average of 22 (England worst – 51; best 6) and it has a lower unemployment rate (0.8% compared to the England average of 1.8%), lower child poverty rates 7.2% compared with the England average of 18.6%. As expected with significantly lower levels of deprivation, Rushcliffe displays good health outcomes as compared to the England average despite its older population. Deaths from all causes in under 65 years is at 73.9 compared to the 100 England; hospital admissions caused by injuries in children (0-14 years) is 68.2 compared to the 109.6 England average and obesity and excess weight prevalence’s are significantly better in Rushcliffe compared to England across all ages, and in many instances have the best levels in the country.

As a Multi-specialty Community Provider (MCP) organisation Principia is a local partnership of GPs, patients and community services which has been selected as one of 50 ‘Vanguards’ across the country with funding to lead significant changes in the way local health and social care services are delivered. As part of this, Principia MCP is a registered intensive “Empowering People in their Communities” (EPC) site (see appendix 1). This involves an implementation plan that includes the following elements:

- Work with communities to grow these resources to meet health and wellbeing needs.

- Build a network of supported volunteer roles.

- Deliver of systematic self-care support for people with COPD, diabetes and with 3 or more long term conditions.

Principia’s ambition is to support its communities and clinical teams to begin to change the culture and approach to health and wellbeing. There is recognition that although many good areas of practice exist, but there is disconnection, fragmentation and sometimes duplication between health, local authority and third sector services. There have been tangible successes in delivering improved care and outcomes for people with physical health problems, supported by coordinated and motivated primary care services. However the “disparity of esteem” still exists for people with serious mental illness, whose life expectancy remains far lower than the rest of the population. Advances in healthcare have not been matched by progress in services to prevent illness and support self-care.

Principia aim to address these issues by investing in people and services to address this fragmentation, encourage systematic assessment of patient activation, and support routine referral of people all along the spectrum of health “risk” for self-care support. At the same time, gaps in provision will be identified with a view to further investment and development in years to come.

Principia Vanguard MCP divided population health management into 10 programmes, under the leadership of different clinical and managerial teams. However, there was a recognition that supported self-care and activation is needed across the whole population, and incorporated five MCP workstreams 1-5 (primary prevention, self-care, secondary prevention, ambulatory care sensitive conditions and mental health). The objectives of these workstreams included:

- Increase patient activation in people who see health coaches and community connectors

- Increase uptake of local authority and 3rd sector services provided to support selfcare

- Identify gaps in these services

- Reduce the financial impact on the NHS of people who access these services

3. Developing the ‘Live Well’ Model

3.1 Our Approach

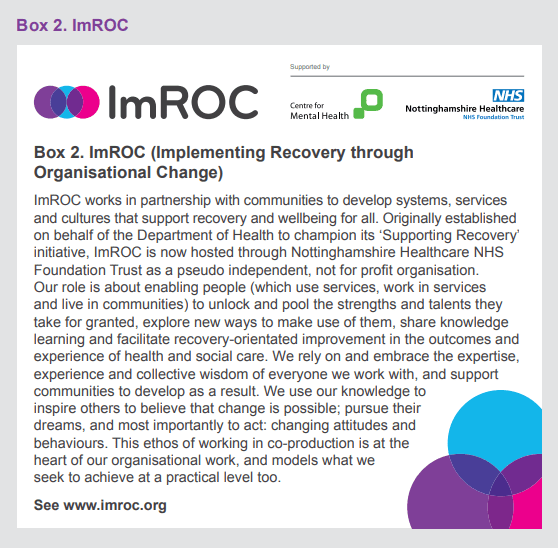

The Live Well model developed through an ongoing co-productive process, continually drawing on the expertise and experience of a range of stakeholders (including General Practitioners and CCG staff with MCP roles for primary prevention/self-care), Local Authority staff including public health, reenablement, parks and leisure and IT staff, voluntary sector groups, emergency services, housing, employment, sports and leisure organisations) and increasingly, as the project progressed, responding to the experiences of staff working in the Live Well team, their clients and the community members with whom they worked. The power of coproduction has been well described (see Box 2): it is about bringing together all available expertise and experience around a shared challenge, to agree on goals, consider research evidence, share personal and professional experience and suggest possible courses of action. A coproduction group can discuss, debate, develop, test, amend and evaluate ideas over time. New solutions are generated, new group members are identified, everyone can both contribute and benefit in a synergy that is not possible in exclusive, closed or solely professional groups.

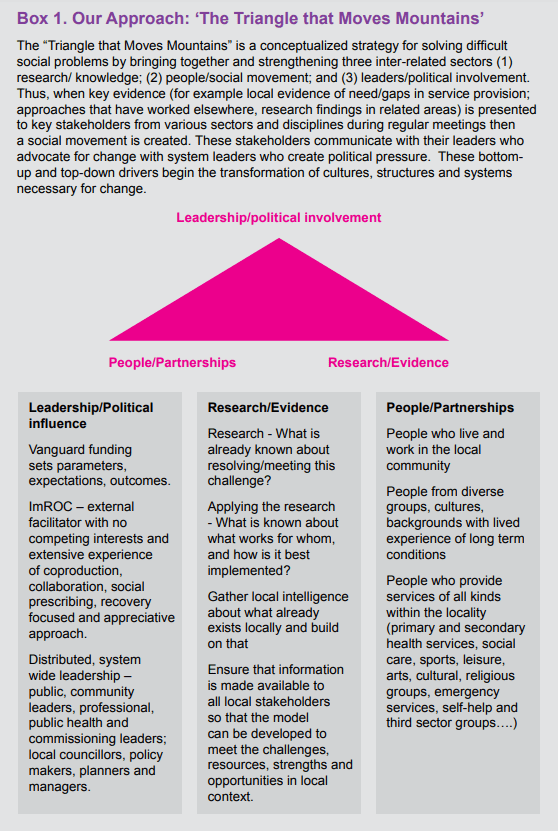

The overall model was informed by the ‘The Triangle that Moves Mountains’ philosophy that has been successful in developing complex social policy transformation in Thailand7. This focuses on three factors: providing relevant evidence, research and examples of practice from elsewhere; working with local people, organisations and resources to develop a ‘community sensitive’ approach over time; and engaging and influencing local leaders to create political pressure to transform systems, (see Box 1).

The Live Well coproduction group met regularly throughout the project. Initially agreeing on the nature of existing challenges, the values, aims and objectives to be met (see Box 2). Subsequently reviewing research underpinning potential approaches along with the expertise and experience presented by different members to determine the values of the project, an outline service model and a profile of the people who the project would target. There was a strong commitment to making the service accessible to anyone who felt they might benefit from it so the service initially targeted anyone over 18 years that is registered with a GP Practice in the Rushcliffe.

The ideas of the coproduction group were developed into a proposal which was successfully submitted for funding from Rushcliffe MCP Vanguard Site. The implementation of the model was then considered by the group and the project goals, objectives and time plan were agreed; values were developed. Relevant expertise within the group was utilised in the recruitment of staff (who were required to bring diverse lived and life experience which they could explicitly apply in their practice); the training of project staff (with input from coproduction group members for example Public Health England; NHS England; Local Authority leads for coproduction and for community learning.

Box 1. Our Approach: ‘The Triangle that Moves Mountains’

Perhaps the most innovative aspect of the coproduction process was the ongoing influence of the group on emerging challenges and the development of new initiatives for the whole community (for example the development of new learning opportunities across the whole patch and the development of community cafés in rural areas, a university campus and small towns). These partnership initiatives – involving religious groups, local public houses, sports centres, libraries, subject specialists and self-help groups – attracted an ever increasing group of coproduction group members, including key influencers, leaders and funders so that the model gradually infiltrated and strengthened a widening range of opportunities with the synergy to impact on the whole population in the locality.

“I came along to the Co-production meeting yesterday … and what a wonderful meeting it was! I found myself reflecting on the meeting last night and how powerful the sharing of stories, backgrounds and passions were … I fully appreciate that it took time but I feel it was incredibly valuable in developing those vital relationships and genuinely coproducing a community endeavour – full of admiration for you and what Lets Live Well in Rushcliffe is achieving!”

Newark Mind – co production partner

3.2 Project Leadership

One of the counter-intuitive aspects of any coproduction is the need for leadership. Although coproduction is all about partnership on an equal basis, unless the process is informed, facilitated, led and ‘serviced’ then it will stagnate as everyone waits for someone else to speak up or develop some rules or make a decision…. Yet the challenge facing any local provider who leads the coproduction process is the inevitable competition that exists between themselves and other members: all are likely to be chasing the same limited funding and the elevation of a local group to lead a project can exacerbate rivalry. Commissioning of services is generally based on a competitive tendering process which means that some services win and others lose out on funding. Coproduction, on the other hand, is all about mutual benefit generated in an open, transparent, sharing culture: win-win.

ImROC initiated the coproduction process in the LLWiR project well before any funding was won. Following an approach from a local GP for ideas about meeting the needs of people with severe depression, it was ImROC who suggested that rather than prescribing any solution, we should seek the views of the local community and relevant services and groups about what might work – in a co-productive process. The success of the early coproduction meetings led to increasing commitment to the project by service providers, commissioners, local citizens and ultimately funders. This has driven the ambition and momentum of the project, which has been sustained by well organised, engaging, relevant and mutually beneficial coproduction meetings which reliably lead to inclusive action and progress. The role of ImROC (see Box 2) has been to:

- manage the project in line with the project plan identifying and mitigating potential risks;

- facilitate coproduction meetings and ensure that decisions and plans made in the group are implemented as agreed enable the project to evolve organically over time in response to the experiences of project staff and clients and in line with the decisions made in the coproduction group;

- seek relevant evidence and expertise to ensure that the coproduction group is working with best research evidence and practice guidance rather than relying solely on local people’s experience (as required in the Triangle that Moves the Mountain);

- lead the recruitment, training and employment of staff;

- enable and oversee the evaluation of the project within the defined budget.

Overseeing the project, a steering group (with local and national representation from all sectors as well as ‘patient’ and peer worker representation ), chaired by a local GP met regularly to review progress, challenges and risks against the project plan.

Box 2. ImRO

Box 3. Coproduction

Coproduction is all about bringing together everybody involved in an issue to work in partnership, make decisions, deliver solutions, evaluate, review and respond together. As Nesta1 point out: “Co-production challenges the conventional model of public services as a ‘product’ that is delivered to a ‘customer’ from on high, and instead genuinely devolves power, choice and control to frontline professionals and the public”. By facilitating reciprocal and equal relationships, coproduction enables all participants to both contribute and benefit from the process so that change becomes more relevant, inclusive and effective. The New Economics Foundation2 have claimed that coproduction is an effective way of building up the local economy engaging, enabling and expanding the resources available. In his introduction to the NEF report, Edgar Cahn explains how coproduction is the root of community development:

“If social capital is critical to the well-being of society, then we must ask what its home base and source is. Social Capital is rooted in a social economy – and surely, the home base of that economy is the household, the neighbourhood, the community and civil society. That is the economy that co-production seems to rebuild and to reconstruct”.

NEF describe the elements of co-production within public organisations as:

- See people as assets, not burdens on an overstretched system – people are the real wealth (and wasted resource) in society – more than passive recipients in services.

- Invest in the capacity of local communities – so that communities shift from expecting professionals to have all the answers and take greater responsibility for themselves, building social and cultural capital, nurturing economic and mental capital.

- Use peer support networks to transfer/develop knowledge and capabilities so become a networked organisation with multiple partners.

- Reconfigure services to blur the distinction/change the power balance between producers and consumers of services – value work differently and create a demand for all contributions and reward appropriately.

- Public service agencies thus become catalysts for change rather than simply providers.

ImROC has described their experience and learning about coproduction and conclude with Ten Top Tips for Coproduction3:

- Gather the right people for the job.

- Just get started and build momentum around your shared purpose.

- Spend time agreeing the structure and the values of meetings.

- Support every member to contribute to their full potential.

- Tackle the challenge in small steps.

- Listen, listen, listen.

- Back up decisions with evidence.

- Beware the comfort zone.

- Look to the bigger picture.

- Cherish what you create.

1 NESTA (2010)Public Services Inside Out. London: NESTA

2 Ryan-Collins, J. and Stephens, L. (2008) New Economics Foundation: Co-production – a Manifesto for growing the core economy

3 Lewis, A., King, T., Herbert, L. and Repper, J. (2017) 13. Briefing paper 13. Co-Production – Sharing Our Experiences,Reflecting On Our Learning. Nottingham: ImROC

3.3 Developing project goals and agreeing underpinning values

The Live Well model aims to empower and enable local people to live well within their communities drawing on local resources and meeting local needs. It has the potential to target different groups within the population (for example older people, younger people, people with specific conditions; people from different minority ethnic groups); to focus on prevention (through health education, smoking cessation, weight reduction, community inclusion) and/or ongoing support (for people with existing conditions); to prioritise different activities (such as workplace wellbeing, access to employment and engagement with services). The specific goals of every project will be different – depending on the funding opportunities, local priorities and the local situation. However, it is important for the whole community, represented in the coproduction group, to be clear and united in setting the goals and values of the project.

The process of agreeing goals and values is an effective way of bringing together the coproduction group in productive relationships. The agreement of goals provides a clear focus and parameters for the project and is key to the establishment and ongoing membership of the coproduction group. The agreement of underpinning values for the project set the culture of the coproduction process, the values are the guiding principles that are most important to the group about the way that they work together. They guide decision making, influence the nature of conversations, inform the training and supervision of project staff and the ongoing development of the project.

3.3.1 The Goals of LLWiR – developed and agreed by the Coproduction Group:

We aim to improve the lives of people in Rushcliffe who are isolated, inactive and/ or have long term condition(s) by:

- Supporting and enabling them to do the things they want to do – demonstrating an increase in roles, relationships and activities and improvement in personal goal attainment scales.

- Increasing their understanding of their own condition and improving their ability and confidence in managing their own condition – demonstrating improvement on PAM Scores.

- Reducing their reliance on health services – demonstrating reduction in crises, unplanned admissions and frequency of GP attendance.

- Increasing engagement in local communities – demonstrating increase in activities, engagement with local community amenities, and achievement of personal goals.

- Increasing partnerships between different organisations and sectors to reduce duplication and gaps between services – demonstrated in discussions at coproduction meetings.

- Identifying gaps and developing new, accessible opportunities – demonstrated by collecting weekly updates about their community development activities from link workers.

3.3.2 The Values underpinning LLWiR – developed and agreed by the coproduction group

Live Well draws on the extensive experience of coproduction group members. Their collective belief in the potential of all citizens reflects a ‘Recovery’ approach. The term Recovery has been reclaimed by people with mental health problems to refer to their ability to live well in the presence or absence of symptoms of their condition8. For services to focus on Recovery they need to shift their focus from symptoms and problems to strengths, assets, experience and goals. For people to achieve recovery they need to identify their own goals – and work out what sort of information and support will enable them to achieve these goals. For communities to support recovery they need to become more confident about their own abilities to accommodate, support and benefit from the contributions of people who experience different conditions. Our values are quite simply:

To always inspire Hope by demonstrating our belief in people: everyone has the potential to live a more fulfilling and satisfying life.

To empower people to take Control of their own condition, their own treatment and their own lives.

To enable people to access the Opportunities (facilities, activities and resources) that will enable them to achieve their life goals9.

3.4 Integrating the service into GP practice

Living Well was originally conceived as part of the Rushcliffe NHS new care models vanguard- Principia MCP -and a business case was written and accepted to fund a pilot project that has evolved to become Lets Live Well in Rushcliffe. The return on investment was predicated on a reduction in the use of NHS services by people supported by the service. It was designed to be integrated and colocated with NHS GP services: this was necessary to get the service up and running, using the regular contact that people have with GPs and health centres to drive uptake and visibility.

In the first phase there have been three different referral pathways. Firstly people who are opportunistically identified during consultations with GPs are offered a health coach assessment. Secondly, patients attending for their annual long term condition health check, usually with a nurse, can be offered a referral. Finally, GP computer disease registries were analysed for people with characteristics suggesting they may benefit from the service, and invited by letter. Examples included people with serious mental illness at risk of developing further long term conditions.

Referrals have been made as easy as possible using a simple “E-referral” system embedded in the clinical IT system used by health care professionals every day. Health Coaches and Link workers use the same system to record their activity, making it simple for NHS professionals to see what has happened.

General Practice teams continuously recognise people who’s health wellbeing are influenced by psychological and social factors more than medical issues. It has been a source of frustration for GPs and nurses that they have had neither the time to address these problems, or any places to direct patients for support.

As GPs on the steering group have reflected, many clinicians have felt it is their job to deal with medical problems alone, with many very reluctant to explore concepts such as activation, address the social determinants of health, or support lifestyle change. With these factors in mind, there has been a concerted effort to communicate the benefits of Living Well during the first few months. GP leaders have visited practices, attended MDT meetings and presented at educational events. The evidence base for this approach, detailing the potential improvements in quality of life for Rushcliffe citizens, alongside reductions in use of NHS services has been emphasised. Real-life stories of local patients whose attendance at the GP surgery has dramatically dropped following their introduction to the service has helped support this message.

‘There is a feeling, supported by the early evaluation interviews, that hearts and minds are changing amongst medical teams. All practices, and most GPs have made at least one referral to Living Well. Stories of people’s lives being transformed are being discussed in clinical teams. The early adopters and enthusiasts are delighted to have an option to help people in a truly holistic way’

GP on steering group

4. Components of the Live Well model

4.1 Community Development

The Live Well model seeks to address the needs of the local population not only by changing local services, but by engaging and developing the communities that they serve. This allows health and social care services to focus on those people requiring specialist treatment and support, whilst communities offer roles, relationships and supports to maintain the wellbeing of the whole population. All communities offer a wealth of untapped resources, expertise and interest. There is ample evidence of the generosity, expertise and support that exists within communities, perhaps most marked in those facing crises – seen most recently in the UK following the Grenfell disaster. Community development approaches have rapidly developed over the past three decades (although different names have been used to describe this work – increasing social capital, community empowerment, improving social value, participatory and action research methods…). They essentially refer to working with communities to identify and build on existing resources, develop new resources, give everyone the opportunity to both engage and benefit from their community and contribute to it (see Box 6).

Within the Live Well project, new relationships have been developed in the coproduction group leading to partnership initiatives to meet the need of Live Well Clients and local communities. For example the Local Authority funded Library service has worked with link workers to a) increase the range of learning opportunities accessible and relevant to Live Well clients (including selfmanagement courses); b) increase the use of existing library facilities and opportunities by Live Well clients; and c) develop new courses and groups running in libraries. These new courses and groups are available to everyone in the community, not only Live Well clients – thus benefitting the whole community.

‘Following a ‘meet your village’ event in East Leake, LLWiR will be working with the Rotary Club, Lings Bar hospital and others to establish a Dementia café in East Leake and Kegworth. Rushcliffe Golf club want to meet with LLWIR and have offered use of their facilities to support a dusk time walking group. They are approaching Sport England to explore opportunities for golf to be more accessible in the community.’

Health Coach

Link workers and Health coaches are employed in one specific CCG care delivery group (localities of North, Central and South) and an early priority for each of these ‘placebased’ teams was community asset mapping. This involved visiting local resources and facilities and sharing the nature and purpose of the Live Well team as well as gaining an understanding of the resource: who it serves, what it offers, how accessible it is, whether they would like any further information or engagement with the Live Well team. This work was invaluable in the success of the Live Well project. Local teams were able to signpost clients to appropriate activities and to the right people within those activities. Local resources were able to join the coproduction group if they were interested. They might receive training and other types of support from the Live Well team to improve their accessibility and confidence (so, for example training on ‘working with people who hoard’ was offered at the request of the Fire Service and Housing Associations). Some worked in partnership with the team to develop new activities; others offer material support to the team (for example free facilities for groups).

Since starting the Notts County Football in the Community groups in Cotgrave and East Leake, we have had one gentlemen who has really benefitted from the groups who struggles with anxiety. He said: “I have opened up more to you guys in two sessions than I have with any therapist”

Link Worker Community Development

Setting up the East Leake Walking Group

I met with an individual at a health week event in December 2017 in East Leake Library. This individual and her daughter were keen to start a local walking group as there was nothing around locally with the nearest group being in Ruddington. Together, we agreed to make this idea a reality and begin building the group together. I met with the two on several occasions and helped them with creating a digital flyer to advertise the group as well as getting the group onto the Notts Help Yourself website. I helped to get the advertising material printed and distributed. On the 11th of January the group had its first walk with a good group of people turning up. I supported this group continuously on the walk each week thereafter. The walk commences each Thursday at 1.30pm and ends with a cup of tea or coffee and a chat in the local café. It has been fed back that the group is a really brilliant way to be active for those who want gentle exercise, but also a fantastic group of people to socialise with who are very welcoming and generally nice.

Anne, the walking group lead had this to say recently:

“Last week we had a bumper turn out with 9 people walking, two new people and 10 for tea!

We have now had 19 walks, 18 different people involved and 111 attendances which average out at about 6 people each week.”

This group is looking like something that will be around for a long while in the future.

Box 4. Community Development

What is community development?

Community development is variously defined as either a process or an outcome; a socio-political movement or an interpersonal phenomenon1. It includes:

- Empowering communities by strengthening the capacity of people as active citizens through their community groups, organisations and networks, and

- Empowering institutions and agencies to work in partnership with citizens to shape and determine change in their communities.

- Promoting the voice and action of disadvantaged and vulnerable groups by working with excluded groups in active process of participation, learning, action and reflection.

- Promoting strong communities by facilitating full active partnership in a mutual and reciprocal solution focused process focused on common problems or the prevention of such problems; increasing the confidence and capacity of local communities to understand, accommodate and appreciate everybody in the local population.

- Facilitating collaboration between individuals, interest groups, government, local organisations and funding agencies.

- Supporting the local population to define and voice their own wishes and needs and maximise their political influence (to achieve funding, support, recognition…).

In practice these processes redefine the relationship between the secondary and primary stakeholders so that the role of the outside agent shifts from ‘expert’ to enable; from advisor to catalyst releasing the ‘power-from-within’ the primary stakeholders2.

What do we mean by Community?

Within the Live Well model, we are primarily focusing on the population of a defined geographical locality, within this locality we focus on specific communities – these might be defined by interest, condition, profession, religion, politics, gender, culture or age, and we prioritise those whose needs are not being met with existing resources. The people who we work with are often multiply excluded on the basis of different characteristics such as (dis)ability, personal resources, race, religion, reputation and age. People with mental health problems, particularly schizophrenia, are among the most excluded in Western society so particular attention is paid to their inclusion in all Live Well coproduction processes.

Asset-Based Community Development3

(ABCD) “While deficit approaches focus on problems and deficiencies and designs services to fix these problems, they create disempowered and dependent communities in which people become passive recipients of services rather than active agents in their own and their families lives”. The Live Well model draws on ABCD as it is a well tried and tested approach which: Identifies health enhancing assets in a community; Sees citizens as co-producers of health and wellbeing rather than passive recipients; Promotes community networks and relationships that provide caring, mutual help and empowerment; Supports individuals wellbeing by increasing selfesteem, coping, resilience, relationships and personal resources; and Empowers communities to take control over their own future and values and create tangible resources such as services, funds and buildings.

1 Wallerstein N. Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 2002, Suppl 59:72–77

2 Fetterman DM. Empowerment evaluation: building communities of practice and a culture of learning. American Journal of Community Psychology, 2002, 30(1):89–102

3 http://www.assetbasedconsulting.net/uploads/publications/A%20glass%20half%20full.pdf

4.2 Social Prescribing

Many people in the UK live in situations that have a detrimental effect on their health, indeed, it has been estimated that around 20% of patients consult their GP for what is primarily a social problem and 15% of GP visits are for social welfare advice10. Social prescribing is a way of linking primary care patients who have ‘psycho-social problems’ with sources of appropriate, non-medical support in the community. This has been seen as one way of making General Practice sustainable11 an approach to integrating health and social care with the voluntary and community sector.

Social prescribing began as a way of engaging people with mental health problems with activities and supports within their communities as a non-medical referral option to improve health and wellbeing12. It has developed into various forms, all offering support to people who are inactive, isolated and/or struggling with a long term condition. Whilst there are social prescribing initiatives that focus solely on ‘prescriptions’ for nonmedical support from general practitioners, others are based entirely in the voluntary sector. Whilst some focus entirely on arts or exercise prescriptions, others offer prescriptions for broader social support. Whilst some have narrow referral criteria, targeting people with certain conditions or levels of disability, others offer support to anyone who is referred or self-refers. Whilst some link people to a few selected groups, others link people with a range of resources determined by the person’s personal interests and goals. Whilst some offer information and signposting, others offer face to face practical support.

Social prescribing schemes generally have three key components:

i) a referral from a healthcare professional,

ii) a consultation with a link worker and

iii) an agreed referral to a local voluntary, community and social enterprise organisation.

“After working with the link worker I swim regularly which helps me manage my pain, I drive to new places unsupported, which helps me do the things I want to do! My next step is to volunteer with LLWiR”

Studies into the effectiveness of social prescribing are generally small, conducted over short time periods with different outcomes measured, however results are promising. The most recent systematic review of research into social prescribing concludes that: “Such interventions have been found to be cost-saving13, able to address the mental health needs of hard-toreach populations14, 15and help to combat loneliness16. Importantly, the provision of care outside clinical settings can facilitate the development of social relationships and widen individuals’ social networks. … Social relationships are positively associated with better physical and mental health, and have been shown to reduce mortality risk to an extent that is comparable to stopping smoking and reducing alcohol consumption17”,18.

The Live Well approach to social prescribing has been developed in the coproduction group. Rather than providing a service that simply connects clients with existing groups, this has focused on link workers engaging with people to identify their own goals. Using our ‘Green Book’ (another coproduced product, see Box 9), people are supported to develop their own wellbeing plan, working out how they can keep themselves as well as possible, how to recognise and respond to signs that they are having a bad day or ‘relapsing’, and planning action they can take to prevent a crisis. The Green Book also draws on the Five Ways to Wellbeing19 to support people to generate personal goals and prioritise ‘SMART’ action plans to begin working towards these goals. Link workers will support people over 6-8 sessions; for some people, support will include identifying and engaging in existing local groups or activities, for others it will focus on changing their behaviour – in relation to diet, daily routine, exercising or socialising; for others it will involve considering their employment – diary/time management, organising appropriate adjustments to their role, accessing relevant training. Where there are no appropriate groups or resources locally, the local Live Well team will consider how and whether to set up a new group, or they may come back to the coproduction group for their advice and ideas about how to respond – asking the group: who can help with this, what exists elsewhere, where is there relevant expertise and experience in this area.

An individual was referred to me via the GP. The individual struggles with managing their Type 2 Diabetes as well as feeling lonely due to the passing of their partner. The individual was not routinely taking their medication to best manage their Diabetes as they didn’t see the point. Since my contact with the individual, we have sorted home delivery of her medication to help her to be better organised in taking them at the correct times. We also discussed using weekly tablet trays and this individual has since not missed any of her medication. We worked a lot on motivation and have seemed to make good improvements. They feel much better in themselves and we are now working with them to join a walking group, something the individual wants to do to meet new people and get some exercise to help the management of their condition. Very positive steps are being made and I can see the difference in this individual’s attitude myself. They are much more positive now since our contact.

Box 5. The Green Book

Everyone referred to Live Well is provided with a ‘Green Book’. This is a self-completion tool with information and encouragement to work out how to keep well, prevent relapse, identify personal goals and make a plan to achieve these goals.

The Green Book draws on Wellness and Recovery Action Planning (WRAP)1 to help people recognise their own understanding of their condition and build on this to keep themselves well. It begins by supporting people to identify what makes them feel well, what seems to make them unwell, stressed or miserable (triggers) and how they recognise signs that they are becoming unwell. It goes on to help them use this information to make a plan to increase the things that keep them well and mimimise or avoid makes them, then to make a plan for managing early warning signs.

The Green Books uses the Five Ways to Wellbeing2 to help them to identify some personal goals that are meaningful them and build on their interests and experiences. Evidence suggests small changes in these areas can help to improve personal wellbeing:

- Connect – There is strong evidence that indicates that feeling close to, and valued by, other people is a fundamental human need and one that contributes to functioning well in the world.

- Be active – Regular physical activity is associated with lower rates of depression and anxiety across all age groups. Exercise is essential for slowing age-related cognitive decline and for promoting well-being.

- Take notice – Reminding yourself to ‘take notice’ can strengthen and broaden awareness. Studies have shown that being aware of what is taking place in the present directly enhances your well-being and savouring ‘the moment’ can help to reaffirm your life priorities. Heightened awareness also enhances your self-understanding and allows you to make positive choices based on your own values and motivations.

- Learn – Continued learning through life enhances self-esteem and encourages social interaction and a more active life. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the opportunity to engage in work or educational activities particularly helps to lift older people out of depression. The practice of setting goals, which is related to adult learning in particular, has been strongly associated with higher levels of wellbeing.

- Give – Individuals who report a greater interest in helping others are more likely to rate themselves as happy. Research into actions for promoting happiness has shown that committing an act of kindness once a week over a six-week period is associated with an increase in wellbeing.

The Green Book helps people to think about ways they could increase their activities in these areas and uses this process as a way of enabling them to set personal goals and make more detailed action plans.

Since the Green Book is a loose leaf booklet, individuals can add their own notes, and they can insert specific tools and information (coproduced by the Live Well team) as relevant to their own condition and lives.

1 http://mentalhealthrecovery.com/

2 http://issuu.com/neweconomicsfoundation/docs/five_ways_to_well-being?mode=embed&viewMode=presentation

4.3 Health Coaching

One of the underlying problems of our time is the construction of all health and social care problems as requiring professional help – from health and social services. We are increasingly a nation of ‘consumers’ socialised into believing that the best sources of help for our problems – whether long term pain, disability, mental health and physical problems or housing, employment and isolation – comes from public services. We have lost confidence in our own abilities to manage our own lives and conditions, and the breakdown of traditional communities contributes to a lack of confidence in communities as a resource to which we can contribute and from which we can gain meaningful roles and relationships. Many people who are house bound, disabled by ongoing mental and physical conditions, anxious about going out and meeting people, lacking confidence following diagnosis or illness have no understanding of their condition and how to manage it, they are not aware of what is possible for them or of what sort of supports and activities exist in their local community. In reality, we can all make a difference to our own health – whether preventing conditions arising or managing a long-term health conditions. It has been estimated that as many as 70 per cent of premature deaths are caused by behaviours that could be changed (Schneider, 2007). Clearly, huge benefits could be realised if people felt able to take a more active and engaged role in their own health care.

Research into ‘patient activation’ demonstrates the positive impact that empowering people to manage their condition and thereby continue a more active and meaningful life can make on health inequalities, outcomes, the quality of care and the costs of services (Box 10). A new role has developed to support patient activation: ‘health coaching’, which focuses on enabling the person to gain new skills in managing their condition, encouraging a sense of ownership of their health, considering changes to their social environment to support their wellbeing, and linking with relevant education, activities and opportunities.

Within the Live Well Model, the Health Coaches receive training in coaching and patient activation; they work closely with primary care teams to clarify their role and the sort of people who might benefit from health coaching. They supervise the link workers in their area and are the local contact point for anyone wanting to contact the team or considering making a referral. Health coaches see all new referrals to the service, initially engaging and assessing their situation and agreeing a way forwards that is most suitable for that person. Health coaches are not experts in long term conditions and their treatment, rather, ‘they are experts in not being the expert’20, they work in partnership with the client to find out the information and gain the skills the person needs. This might be through locating relevant literature either on the internet or in paper form; it might involve finding a relevant course or self-help group in the locality, it might be solution focused work or problem solving to work out a plan of action. The focus is largely on health related behaviour, with support being provided over 1-5 sessions. Where ongoing or social support is needed the health coach introduces the client to a link worker.

Saw a 54yr old in Jan 2018…BMI 35, 40u /week daily drinker, hypertensive with a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Offered meds for the DM but he declined saying he wanted to adjust his lifestyle. He’s been working with the health coach on goal setting for the past 4 months. In 12 months, he has dropped his Hba1c from 63 to 44, drinks lightly now on only two days /week and has lost a decent amount of weight.

It’s all going really well, I’m drinking less, I’ve not had a cigarette for 4 weeks and my link worker is supporting me to become a volunteer– Thank you!”

Feedback from GP

Box 6. Patient Activation and Patient Activation Measure (PAM)

In the Kings Fund’s review of the research into patient activation, Hibbard and Gilbert1 conclude that patient activation is a better predictor of health outcomes than known socio-demographic factors such as ethnicity and age, with people who are more activated being significantly more likely to attend check-ups, adopt positive behaviours (eg, diet and exercise), and have clinical indicators in the normal range (body mass index, blood sugar levels, blood pressure and cholesterol); and people who are less activated being significantly less likely to prepare for a medical visit, know about treatment guidelines or be persistent in clarifying advice. Not surprisingly, patient activation scores are related to cost to services with less-activated patients costing approximately 8 per cent higher than more-activated patients. Studies of interventions to improve activation (such as Health Coaching) show that people who start with the lowest activation scores tend to increase their scores the most, suggesting that effective interventions can help engage even the most disengaged.

The Patient Activation Measure2 (PAM) is a simple, evidence-based tool for establishing the capacity of individuals to manage their health – and then using that information to optimise the delivery of care. PAM scores have been demonstrated to be related to most health behaviours, many clinical outcomes, health care costs and patient experiences. The Principia Vanguard applied to NHS England to be an intensive pilot site for “Empowering People & Communities” and as a result were accepted to use PAM, one of three intensive EPC sites across East Midlands. Within the Live Well model, the PAM is included in all baseline assessments to establish the intensity and focus of subsequent support. It is measured at three monthly intervals to provide both the health coach/link worker) and the patient with feedback about progress.

The PAM consists of 13 statements about beliefs, confidence in the management of health-related tasks and self-assessed knowledge designed to assess the extent of a patient’s activation. Patients rate the degree to which they agree or disagree with each statement giving a combined single activation score of between 0 and 100. For the purpose of intervention, these scores are divided into four groups or levels of activation, each requiring a different level and type of support.

- Level 1 – Individuals tend to be passive and feel overwhelmed by the idea of managing their own health. They may not understand their role in the care process.

- Level 2 – Individuals may lack the knowledge and confidence to manage their health.

- Level 3 – Individuals appear to be taking action but may still lack the confidence and skill to support their behaviours.

- Level 4 – Individuals have adopted many of the behaviours needed to support their health but may not be able to maintain them in the face of life stressors.

1 Hibbard, J. and Gilbert, H. (2014) Supporting People to Manage their Health: An introduction to Patient Activation. London: Kings Fund

2 Hibbard JH, Collins PA, Mahoney E, Baker LH (2010). ‘The development and testing of a measure assessing clinician beliefs about patient self-management’. Health Expectations, vol 13, no 1, pp 65–72.

4.4 Education

Education is central to personal ‘power’, identity and autonomy, status and life choices, so inevitably it is closely linked with health and wellbeing. In relation to general education, an additional four years of education lowers five-year mortality by 1.8 percentage points; it also reduces the risk of heart disease by 2.16 percentage points, and the risk of diabetes by 1.3 percentage points. People who are better educated report having lower morbidity from the most common acute and chronic diseases (heart condition, stroke hypertension, cholesterol, emphysema, diabetes, asthma attacks, ulcer) and are substantially less likely to report that they are in poor health or have anxiety or depression and spend fewer days in bed or not at work because of disease. Whilst we can rarely address a lack of general education, we can offer health related education to enable people to understand how to keep themselves well. In a review of the impact of health education, Lawn et al (2011) report improved self-management, reduced crises and unplanned admissions, reduced frequency of service use, improved social networks and greater confidence and self-efficacy. The development of Recovery Colleges (Perkins et al, 20011; 2018) offering coproduced, experiential and recovery focused education, primarily for people with mental health problems – but increasingly open to the whole population – has demonstrated the huge popularity, accessibility and benefits of learning with and from peers (see Box 11).

The Live Well project did not set out to provide self-management courses or group based learning opportunities, but it became apparent that many clients wanted to learn about their condition and how to manage their lives with their condition, but accessible, condition specific courses were not always available. Whilst a Recovery College does exist in Nottingham this is only open to people using secondary services and in primary care teams funded to provide courses.

The coproduction group considered this challenge and the Local Authority funded Inspire21 project offered to work in partnership with link workers to enhance the accessibility of courses and the range of learning opportunities already offered in local libraries to meet the needs of Live Well clients. In addition, specific courses were developed in response to identified need, for example healthy eating courses have been developed in partnership with a local nutritionist to provide dietary information alongside cookery classes for people who want to develop their own understanding and skills but do not feel able to join mainstream education.

As the project progressed, it became clear that local groups and services would also like to be able to access training to enable them to maximise their contribution to local people with long term conditions. This challenge was discussed at the coproduction group who drew on their expertise, networks and experience to focus on the best way of strengthening learning opportunities within the locality. The group were able to produce a list of learning opportunities already available and identified the need for additional courses focusing on self-management. It was agreed that a part time trainer should be employed to coproduce (with a peer link worker) bespoke training in subjects nominated by the coproduction group, like ‘mental health awareness’, ‘setting up community groups’, ‘understanding and managing hoarding behaviour’, for any member of the coproduction group, any of the Live Well team and any clients who would like to attend. In addition, to sustain the provision of training, Live Well staff were offered ‘training for trainers’ an accredited training course that enabled them to coproduce and co-facilitate training wherever it was needed.

Box 7. Recovery Colleges – Core Principles and Evidence of Effectiveness

Recovery Colleges have developed over the last ten years to become a key feature of mental health services in the UK and beyond. More recently they have developed in primary care, forensic, homeless, housing and third sector services. They offer courses based on the wishes and needs of those who use them and embody a shift from a focus on therapy to the inclusion of education to enable students to learn how to manage their own condition and their own life – housing, diet, sleep, activity, relationships …. They explicitly bring together the expertise of lived experience and professional expertise in an inclusive learning environment in which people can explore their possibilities.

Although there are now more than 85 Recovery Colleges in England, to date there are no formal controlled trials exploring their effectiveness. However, there is a strong and consistent body of evidence from an increasing number of uncontrolled studies of the positive impact of Recovery Colleges in several areas.

- The effectiveness of Recovery Colleges on people facing mental health with the vast majority of students achieving personal goals, moving on to volunteering, training, open employment and education.

- The quality of recovery-supporting care: Recovery Colleges are popular and students are highly satisfied with their experience.

- Positive evaluation of the staff attending Recovery Colleges

- Recovery Colleges are an effective vehicle for driving a change in the culture of organisations with improved staff attitudes and understanding and a higher value placed on coproduction and peer support.

Perkins et al22 review the development and research into Recovery Colleges and conclude with 6 key principles that both define them and account for their success.

- They are based on educational principles but do not replace formal individual therapy or mainstream educational opportunities.

- Coproduction, co-facilitation and colearning lie at the core of their operation: they bring together lived/life expertise with professional/subject expertise on equal terms.

- They are recovery-focused and strengths-based in all aspects of their functioning. They do not prescribe what people should do but provide a safe environment in which people can develop their understanding to keep themselves well and build skills and strategies to live the lives they wish to lead.

- They are progressive, actively supporting students to move forwards in their lives both by progressing through relevant courses that enable them to achieve their identified goals ,and by identifying exploring possibilities outside services where they can move on in their lives and work.

- They are integrated with their community and can serve as a bridge between the services and communities: serving as a way of promoting a recovery-focused transformation of services more generally, and creating communities that can accommodate people with long term conditions.

- They are inclusive and open to all. People of different ages, cultures, genders, abilities and impairments, as well as people in local communities who have health conditions/physical impairments), people who are close to them and people who provide services.

Education – Case example

I have been supporting an individual in the Rushcliffe South area to reconnect with their local community in the hope that this will support them to further manage and reduce their anxiety. This anxiety has adversely affected employment and living arrangements, and social circumstances.

The individual wants to start gaining some more independence and manage her anxiety throughout the whole day. I have worked with the Individual to explore their needs and identified the possibility of attending courses which would benefit wellbeing, ideally close to home and with small class sizes. We have researched some local groups with smaller class sizes and closer locations.

Part of this work has been to liaise with Inspire (the library education service) to see if they could extend their courses to more local libraries. Inspire have now offered a taster course at the local library, with a possible view to expand. The individual has been accompanied to first few courses and says that accessing the course at their local library helped them to build friendships and networks with people in their local community. Further joint investigation of what the Community can offer is underway regard a range of activities. All the time the team is allowing the individual to express her needs and then look to see what the community can offer.

4.5 Peer Support

There is increasing evidence that support from a person who shares similar experiences and is managing their own wellbeing improves outcomes when compared with standard support23. Although this evidence draws on research undertaken exclusively in mental health services, the LLWiR team and the coproduction group agreed that employees providing health coaching and link working would bring their own experience of living with a long term condition themselves, or caring for someone who does – in addition to the other desirable and essential characteristics of community support workers. This built on ImROC’s experience of developing opportunities for peer support (including training, supervision, supportive employment and development of peers), it also provided an inspirational example for people using the service to follow and was consistent with the coproduction approach at the heart of the project.

Peer support refers to the explicit use of personal experience in the support of others who share similar experiences. The core characteristics of effective peer support have been identified (see Box 8) and the training provided for all employees focused on them understanding and applying these principles in their practice.

Employing peer workers ensures that the project remains true to its values with integral reflection on the accessibility, appropriateness, relevance and likely effectiveness of the developing approach. People who live with a long term condition and manage it on a daily basis bring practical expertise and experience to every aspect of their work. However, the successful and effective employment of peer workers requires exemplary employment support so that they stay well in work and contribute to their full potential. This is not ‘special’ support, but the kind of consideration that every employee would benefit from. For example consideration of reasonable adjustments, a personal wellbeing at work plan, access to additional supervision when times become difficult for an employee.

The preparation and training of all team members was given careful consideration within the coproduction group, and by the ImROC team. An over view of their training is given in Box 9. This was supplemented with monthly team meetings which provided a forum for ongoing development as training needs arose. Issues addressed in this way included: Supporting people in acute crisis; Supporting people to set personal goals; Starting and ending relationships with people you work with.

“The service is one of the major big things that helped me to get better. In fact, I would say that it has been the most important thing in me getting better. I had never spoken to anyone on that level before or with someone who knows what it feels like. Whenever my link worker left I would always feel massively better and like a weight had been lifted off my shoulders. It has taught me how to be compassionate to myself and look after myself”

Case example – Peer Support

In the first meeting with this A, they were very negative. They believed nothing could help them and that they were unable to physically do anything and therefore felt like they had no purpose and no belonging. This person suffers from depression as well as some physical conditions that mean they cannot use their hands, which is how they used to earn their living.

In the second meeting, I tried to keep the conversation as positive as possible. However, the individual kept bringing the conversation back to the past and everything they had lost. I explained through a diagram that things in the past can feel like a large chunk of your life and that we think these feelings will get better in time and that the impact of the past on our lives will get smaller with time. However, I understand that this is not the case. I gave an example of a time when I experienced loss myself and explained that for me, the impact of that on my life didn’t get smaller as time went on. Therefore, to make the impact of that loss in my life smaller, the only thing to do was to grow my life in other areas. Make sure I was seeing friends/family, make sure I was active and doing things, make sure I was taking notice of what I did have and making sure I was trying and learning new things. This seemed to resonate with the individual quite well. The meeting from that point on seemed very positive and we spoke of things they were looking forward to and came up with a plan of what we could discuss in future meetings to help produce of ideas in which the individual could try to ‘grow’ their life to make the past seem smaller in comparison to their overall life.

They said “I really appreciate you coming to see me, talking really does help”.

4.6 Specialist Areas of Interest

The Live Well model offers a range of interventions and types of support to people with a range of different conditions and life circumstances. It is simply not possible for every employee to hold every piece of information about community resources, conditions, approaches and population groups. It therefore works well to support link workers and health coaches to develop an area of special interest. This might draw on their life experience or their previous employment experience, their interests and hobbies or their cultural awareness. For example, an employee with experience of work in a sales and marketing job might take a lead on social media developments; an employee with interest or a qualification in teaching might lead the development of learning opportunities; another might take a lead on sustaining community developments, or working with younger/older people.

These areas of specialist interest need to have direct relevance and utility within the project, so they might not be apparent when the project starts, but can evolve over time. They ae yet another way of modelling Recovery focused practice: building on personal strengths and interests, developing individuals so that they can progress their career.

Within LLWiR, it became apparent that community groups developed by link workers needed additional attention to ensure that they become sustainable in the longer term with less input from the project. A link worker with previous experience of community development was given the lead on monitoring, sustaining and creating a consistent process for developing new community groups and resources. Another worker with an interest in IT and apps development took a lead on working with the University to develop a mobile phone application which listed details of local groups and resources already existing in the area, building on the resources listed on the Notts Help Yourself website. Once it became apparent that volunteers would be employed in the project, one of the link workers with experience of staff support and supervision took the lead on working with the Council of Voluntary Services to develop the volunteer pathway. Many other opportunities have been taken up by employees in line with both their own areas of interest and the evolution of the project.

In order to be successful, these roles need to be rewarding in themselves rather than exploitative. It is important to integrate the roles in personal development plans, support individuals to access relevant training and ensure that supervision covers these areas.

When carefully managed, this system of distributed leadership not only provides personal development opportunities for employees on the project, it also offers a framework for project development, a method of growing the sum of expertise within and available to the whole team, and an approach to working with coproduction group members in a rational and effective manner.

4.7 Developing a Library of Relevant Resources

Resource Library

As the project has worked with many people who face similar challenges, have similar goals and present similar dilemmas for workers, a huge amount of work has been undertaken by both employees in the service and the people they support to research appropriate coping strategies, supportive tools, services, groups, activities. Rather than individuals repeatedly undertaking the same research, all relevant material has been collected together, reviewed and develop into Live Well guides.

So, for example there are now toolkits, information booklets and lists of useful resources for many different long term condition and there is a growing compendium of local services, facilities, activities, groups and clubs available in the local area. These are formatted in such a way that people can insert them as pages into their Green Book.

As the team has developed, there have been a number of difficult situations which have fallen outside the experience and role of the team so the team has drawn on external expertise to develop clear pathways and guidance for managing these. For example, the team has developed Ten Top Tips for supporting someone expressing suicidal ideas and a pathway for accessing appropriate help.

At present these resources are all maintained on a team shared drive, but as the LLWiR mobile phone app is developed this ever expanding library of information will be available to all those using the service.

4.8 Volunteers

The Live Well model offers time limited support (up to 6 meetings with health coaches and/or up to 6 meetings with link workers). Inevitably there are people who would benefit from longer term support to enable them to continue to work towards their goals. Similarly, the goal for new groups and activities set up by Live Well is to become independent and sustained within and by their local community on a voluntary basis.

People who receive support from Live Well, and those who attend Live Well groups are often keen to continue their involvement as a volunteer but their role is limited if there is no process for them to gain DBS clearance and relevant training.

Once again, this situation was communicated to the coproduction group who shared their experience of managing similar challenges and offered their support in various ways. It was agreed that funding from the project would be provided to Rushcliffe Council of Voluntary Services to train and employ volunteers to work on Live Well initiatives.

A small working group was set up to develop appropriate recruitment procedures, training and ongoing supervision of volunteers. Rather than preparing volunteers for one specific role within Live Well, a Rushcliffe wide system was developed so that once recruited, checked and trained, volunteers are able to work with individuals as befrienders, or supporting groups and activities.

The first cohort of volunteer trainees included 22 ex-Live Well clients who wanted to ‘give something back’ and continue their involvement with the project.

Box 8. The core principles of peer support24

- Mutuality – The experience of peers who give and gain support is never identical. However, peer workers in mental health settings share some of the experiences of the people they work with. They have an understanding of common mental health challenges, the meaning of being defined as a ‘mental patient’ in our society and the confusion, loneliness, fear and hopelessness that can ensue.

- Reciprocity – Traditional relationships between mental health professionals and the people they support are founded on the assumption of an expert (professional) and a non-expert (patient/client). Peer relationships involve no claims to such special expertise, but a sharing and exploration of different world views and the generation of solutions together.

- Non-directive – Because of their claims to special knowledge, mental health professionals often prescribe the ‘best’ course of action for those whom they serve. Peer support is not about introducing another set of experts to offer prescriptions based on their experience, e.g. “You should try this because it worked for me”. Instead, they help people to recognise their own resources and seek their own solutions. “Peer support is about being an expert in not being an expert and that takes a lot of expertise.” (Recovery Innovations training materials. For details see www. recoveryinnovations.org)

- Recovery-Focused – Peer support engages in recovery focused relationships by: inspiring HOPE: they are in a position to say ‘I know you can do it’ and to help generate personal belief, energy and commitment with the person they are supporting; supporting people to take back CONTROL of their personal challenges and define their own destiny; facilitating access to OPPORTUNITIES that the person values, enabling them to participate in roles, relationships and activities in the communities of their choice.

- Strengths-based – Peer support involves a relationship where the person providing support is not afraid of being with someone in their distress. But it is also about seeing within that distress the seeds of possibility and creating a fertile ground for those seeds to grow. It explores what a person has gained from their experience, seeks out their qualities and assets, identifies hidden achievements and celebrates what may seem like the smallest steps forward.

- Inclusive – Being a ‘peer’ is not just about having experienced mental health challenges, it is also about understanding the meaning of such experiences within the communities of which the person is a part. This can be critical among those who feel marginalised and misunderstood by traditional services. Someone who knows the language, values and nuances of those communities obviously has a better understanding of the resources and the possibilities. This equips them to be more effective in helping others become a valued member of their community.

- Progressive – Peer support is not a static friendship, but progressive mutual support in a shared journey of discovery. The peer is not just a ‘buddy’, but a travelling companion, with both travellers learning new skills, developing new resources and reframing challenges as opportunities for finding new solutions.