Given the exponential rise in numbers of peer support workers trained and employed in mental health services, the significant funding commitment from Health Education England (HEE) and the inclusion of peer support workers in current mental health policy implementation documents it is time to assess the current position of peer support workers in mental health and social care services in England. This paper considers progress and pitfalls; sources of successes and challenges; the gaps and the future possibilities. It ends with recommendations for policy, funding and practice which we believe are essential if peer support workers are to achieve all potential benefits for those whom they support, the services they work in and for their own personal wellbeing and professional development.

22. Peer Support in mental health and social care services: Where are we now?

Emma Watson and Julie Repper

Introduction

We are living in exciting times for peer support. The role of peer workers seems to be poised on the edge of a great height, having worked incredibly hard to get there. If the conditions are favourable, peer support may be about to take flight into a horizon of culture change and widespread acceptance of this new role. At such an altitude, there are also challenges; the conditions and context surrounding peer support are crucial.

This paper seeks to outline the progress that has been made in peer support in recent years, as well as to present a vision for a future of peer support within services which lays out the conditions needed for it to thrive.

The past 15 years have seen phenomenal change in the employment of people with personal experience of mental health challenges in services. This has built on the benefits of mutual support developed in self- help, user led community groups and natural relationships to become a role within mental health services across the world. From a largely informal approach between people who share similar struggles, peer support has been formalised, and the presence of Peer Support Workers, who are employed within mental health services to use their lived experience of mental distress to support others, is now commonplace.

Peer Support Workers were first employed in UK mental health services in 2009 in small numbers by some NHS Trusts. Early implementers were supported by ImROC, who advocated for the employment of peer workers as part of a wider cultural change toward recovery orientated services (see Shepherd et al., 2010). From here began a long climb, not only for peer support as a concept, but also for individual peer support workers, to become accepted, to find their identity and a coherent role within the challenging environment of mental health services.

In the past 15 years, the calls for an evidence base for peer support, for training and support for peer workers, and for greater employment for peer workers have been, and continue to be answered. In 2019, the HEE peer support benchmarking report found that 862 peer support workers were employed in services (with approximately 86% directly employed by the NHS and the remaining 14% employed by external parties – for example, organisations within the voluntary sector).

In England, peer support workers are valued as a new role by NHSE (HEE/NHSI) with funding provided for peer support worker training, peer supervisor training and infrastructure support during 2021-4.

The employment of peer support workers is a requirement of the NHS long-term plan included in the mental health implementation plan (which envisages numbers of peer support workers growing by 170 in 2019/20 to 2,780 new peer workers employed in mental health services in 2023/4). Some NHS Trusts have already developed a peer workforce that exceeds policy expectations with peer support workers employed across the whole range

of services from Childrens and Adolescents to Older People’s and Dementia Services, in Primary care and Forensic services, in specialist services like substance misuse, perinatal mental health and gender clinics.

Peer support in statutory health and social care services has taken root in a way that seemed unlikely just 10 years ago. The next decade will see a further increase in the number of peer support workers employed within mental health services, with more being employed in a more diverse range

of services than ever before. The HEE national competency framework for peer support workers and the development of an apprenticeship pathway have served to further legitimise and support the peer worker role. However, these successes also present challenges.

In the following section, we frame the current position of peer support around the progress that has been made in the employment of peer support workers in mental health and social care services, and the pitfalls that challenge the future of peer support.

“And the peer support worker was just like a breath of fresh air on the ward. She was just so…she didn’t share a lot of what she’d been through but she shared enough to know that she’d been through things that had been really difficult for her, and now look at her she’s working, that’s incredible. And it just gave me that hope that…I could do that. And I think it like, saved my life [laughs] because she was just…she told me…about some experiences and they were very very similar to mine, and…the fact that she was working was so inspiring to me. And she’d come and see me and sit with me and encourage me to do a little bit and then a little bit more, and then it just build up from there. Umm and I just thought, I just want to do that, that’s what I want to do. And I sort of kept my eyes out”. (Excerpt of interview transcript, Watson 2021)

The peer support worker I had, sort of validated my existence as a person and my purpose in life. And they were someone who believed in me and my place in the world and the importance of my existence, and they didn’t want to get rid of me, they wanted to watch me fly, and saw me as an ability and not a disability. If she hadn’t have had that [shared lived experience] and was just trying to interact with [me] in a way that was supportive but…without getting it, it wouldn’t have worked, and I wouldn’t be sat here now. Because I would never have found trust in my psychologist, in anyone. I think back then I didn’t trust anybody, not even 10%. Somebody asked my name… ‘why do you need to know my name? F*** off’, simple as that. And I think what I needed at that time was to find somebody that I could actually trust. And when I found that trust in [the peer support worker], it kind of helped me to think maybe there’s trust elsewhere too. (excerpt of interview transcript, Watson, 2021)

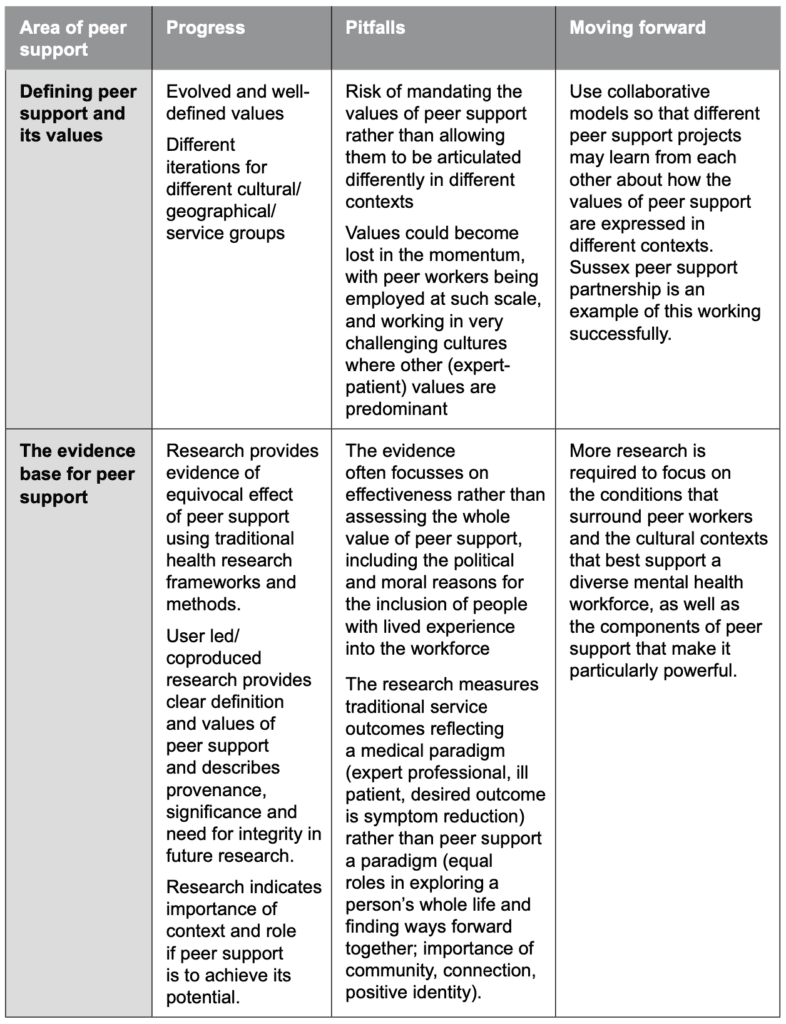

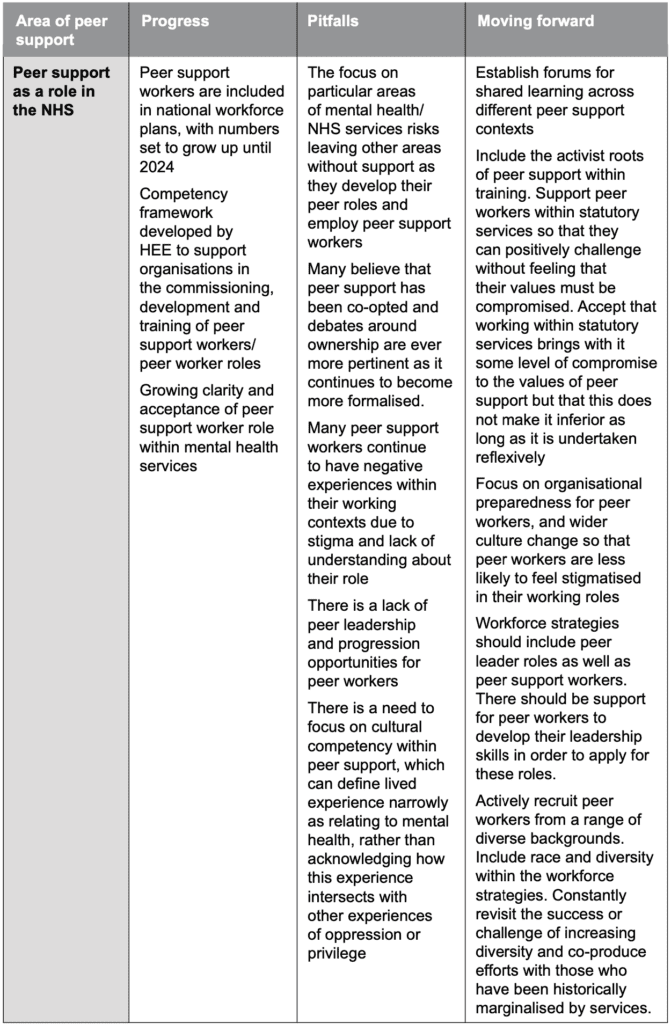

Progress, Pitfalls and Moving Forward

The table below summarises the progress and pitfalls that currently characterise peer support. The far-right column includes some possible ways forward in each area. Following this table, each point is discussed in more detail below.

1. Defining peer support and it’s values

a) Progress

It has long been recognised that the distinctiveness of peer support lies in a unique set of values that sets it apart from professional support (Watson, 2019). Peers – who have some experiences in common – are able to establish safe, mutual, trauma informed relationships with each other;

they spend time together exploring ways of understanding what has happened, ways of coping, and ways of communicating that might be helpful. These relationships are not framed by the offering of advice, but about learning together using the safe, non- judgmental connection as a platform.

While lived experience is essential to peer support, this alone is not sufficient to build the empathetic relationships that are necessary for healing. The values of peer support have roots within the survivor and hearing voices movements, which have campaigned for mental health services that position the person as the expert in their own wellbeing, rather than the disempowering expert-patient hierarchies which have traditionally defined psychiatric services. It was recognition of shared experiences within these campaigning groups that culminated in the service user led redefinition of ‘Recovery’ as a process of people taking control of their own understanding and management of

their own conditions (Chamberlain, 1978). These activist groups have also raised awareness and driven change in relation to the human rights of people with mental health problems – both in terms of social issues (like employment, housing, education, financial resources and adaptations to facilitate full inclusion), and in terms of their rights within the mental health system. Belonging to such user-led groups is not just about mutual support centred on personal challenges, it is also about gaining an empowering identity, being part of a movement, experiencing solidarity alongside others.

As the value of naturally occurring mutual (peer) support has been recognised, it has inevitably become more formalised in a bid to replicate its benefits. Shery Mead, the founder of Intentional Peer Support (IPS) in the US was one of the first to describe the process of peer support and explain its value in mental health services. She developed the notion of Intentional Peer Support (IPS) to differentiate it from that which occurs naturally in an informal support group. IPS is defined by a shift in the focus of relationships (Filson & Mead, 2016) from helping (problem solving or fixing) to a focus on learning together; from a focus on the individual to a focus on the relationship; from fear-based responses to a focus on hope-based responses.

In 2013, ImROC identified eight core principles of peer support that were observed in the practice of peer support workers employed in adult mental health services (through Health Foundation funded research with Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust). These principles were described and illustrated with quotations and practice examples, they include: Mutuality, Reciprocity, Safety, Recovery Focus, Progressive, Inclusive, Strengths-based and Non-directive (see Repper et al., 2013) Similar values and principles of peer support have been suggested by many charity, government and consumer led services in the US, Europe and the UK. The resulting frameworks have been used to evaluate and understand peer support projects. While there are differences in the values frameworks established within different cultural, systemic and geographical contexts, they share some common themes. These include establishing emotional safety, addressing power imbalances, and refraining from fixing or offering solutions.

b) Pitfalls

As the values of peer support are articulated in ever more sophisticated ways, there is a risk of these values becoming prescriptive, or being used to lay claim to certain forms of peer support as more legitimate than others. In practice, context is hugely important in defining the nature and emphasis of peer support. For example, within community based, user led services, there is far greater emphasis on collective activism, with explicit resistance to traditional psychiatric approaches and less emphasis on ‘outcomes’ or ‘progress’ with Recovery. Many argue that the mutual nature of peer support cannot be faithfully applied within mental health services. Where peer workers are paid, are required to assess risk or write notes on/with the people they support, mutuality must be redefined, and compromises must be made. However, it does not mean that peer support has failed if all of the values are not loyally maintained. In fact, we believe that the strength of individual peer workers to apply these values in the most difficult and unlikely circumstances should be celebrated.

c) Moving forward

One of the most beautiful things about peer support is that it can be informed, developed and delivered in a wide range of contexts:

in statutory services and in voluntary sector services, informal spaces and natural relationships. Using their values-based way of working, peer support workers can offer much needed time, hope and self-belief to those using mental health services and peer support offered by community based groups can facilitate positive identities, roles, support and skills to rebuild relationships, roles and activities. These different contexts require different iterations of the values of peer support, so that it can be adapted to best suit the environment and the people involved in offering and receiving it. Rather than seeing areas where the peer support values seem to have mutated as areas of failure, we can look at this, to some extent, as a natural evolution of peer support.

There is an opportunity within current ‘place’ based policies and plans for mental health service provision to grow and develop peer support in all its forms across a given locality. All those individuals and organisations offering peer support might usefully come together to learn from one another, debate key questions, raise awareness of critical issues and potential solutions.

Understanding how peer support is offered in different contexts, and how the values are articulated will improve our understanding of peer support, and increase its influence within the system. This approach has been demonstrated through the development of the Sussex peer support partnership;

a collaboration between 13 different organisations offering peer support (Faulkner, 2021). This partnership provides a model for good practice that has the potential to deliver peer led peer support across a system with

a range of options available for people with different life and lived experience. It works towards four overarching goals:

• to provide peer leadership to define, deliver and influence peer support in the locality;

• to established a shared understanding of what is meant by peer support;

• to ensure that people experiencing mental distress have a choice about the kind of peer support they would like based on the range of services available;

• to influence commissioners so that they recognise the diversity and depth of peer support on offer.

We see huge value in this collaborative model, where peer support services offered in different settings and with different kinds of experience and expertise, work together to provide peer support across a given locality.

2. The evidence base for peer support

a) Progress

There is an ever-increasing body of evidence providing accounts of the impact of peer support. The most positive research comes from first person accounts, narrative research and explorations led or coproduced with people receiving and/or offering peer support. These describe the values based relationships that underpin mutual interactions between people who support each other in their emotional distress (Mead & MacNeil, 2006). Trauma-informed approaches to peer support focus on whole life experiences rather than on an individual’s problems (Blanch et al., 2012), and there is a focus on community and connection rather than simply individual change (Faulkner and Kalathil, 2012). In an exploration of the mechanisms underpinning peer support, Watson (2017) found that people value peer support because of the opportunity it provides for normalizing, nontreatment-based relationships, and Gillard et al. (2015) suggest that it is through relationships that peer support works to strengthen wider connections to community (Gillard, Gibson, Holley, & Lucock, 2015).

Professionally led randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of effectiveness offer more restrained accounts of the benefits of peer support, concluding that peer support workers are broadly as effective as other professionals. They find that peer workers do not appear to achieve better outcomes on traditional indicators of improvement: severity of symptoms, length of hospitalisation, levels of functioning (Bellamy et al., 2017). These studies are largely unclear about the role of peer workers and do not specify how their role differs from that of other professionals. Given the provenance, meaning and nature of peer support, and the difficulty extrapolating the contribution of peer workers when they work as a member of a multidisciplinary team, it is hardly surprising that neither the difference they make, nor the way in which they make a difference, show up in this kind of research.

There are increasing studies into the effectiveness of professionally designed interventions being delivered by peer support workers: cognitive behavioural therapy, self-management strategies, medication adherence, case management (Bellamy et al, 2017) – and in relation to physical health conditions, illness specific education (Repper and Walker, 2019). This may or may not be helpful, but it is not peer support. It replicates and reinforces the traditional expert/patient relationship and illness management approach of psychiatry and is at odds with the core values of peer support: equal power relationships, reciprocal roles of helping and learning and a ‘whole of life’ rather than illness-focused approach).

There is a further body of evidence that demonstrates how the delivery of peer support is influenced by the context, the role of peer workers, their training, support/ supervision, and the opportunities they have to spend time with the people they support. Where peer workers are not supported to develop peer to peer relationships founded on their values then the extent to which they can offer peer support is limited (Gillard et al., 2015b) and peer workers either burn out or conform to the team values and practices. There are exceptions however, Watson found that peer support workers found innovative and imaginative ways of remaining ‘peer’ in their relationships against all odds (Watson 2020).

b) Pitfalls

What is the purpose of amassing evidence about the effectiveness of peer workers? The calls for evidence have not died down since peer workers began to be employed in NHS services. This might serve to calm the fears of those who are wary of the introduction of people with lived experience into the workforce – there now exists far more evidence for peer workers than there are for mental health nurses or psychiatrists (Slade et al., 2017), whose professions are unquestioned.

The evidence might also be used to mount peer workers as the solution to a workforce crisis which at first appears to be win-win: more peer workers and a happier mental health system. However, the calls for evidence into the effectiveness of peer workers and their cost-saving potential risk moving the focus away from the moral and political motivations for employing peer workers. Peer workers not only provide hope and model the possibility of recovery for individuals, but also seek to shift reliance on traditional models of practice that depend on one expert ‘fixing’ one recipient, to a more mutual, human relationship in which peers work together to make sense of events and find their own ways of coping and building meaningful lives. This ultimately challenges current perceptions about the potential and status of people with mental health conditions – social outcomes that are not considered in traditional research. Indeed, the nature and expectations of funded research risks fitting a whole diverse group of supporters working in a range of settings and with non-traditional goals and approaches into a standard research paradigm designed to measure traditional services in terms of service-related outcomes.

c) Moving forward

If further evidence into peer support is needed, it might usefully focus on considering the distinctive contribution of peer support in terms of the identity, role, status, rights, community engagement and/or collective empowerment of peer workers, those they support and people who experience mental health challenges as a whole. What are the ingredients of peer relationships that make it so acceptable, accessible and empowering? And how do we create contexts that are supportive and conducive to peer relationships? These are more relevant questions to be posing than continuing to search for evidence for peer workers’ effectiveness.

A more pertinent area of research still would be to examine the context that surrounds peer workers. It is no secret that there are particular service settings and cultures which peer workers find more difficult to work within than others, and yet this is not well articulated within research. Building a clear understanding of what contributes to a recovery focussed culture and how changes can be brought about will support not only peer workers but the wider workforce, which is in need now more than ever. This is a much more complex question to ask, and would reveal the multi-faceted nature of the cultures to which we are introducing peer support; cultures that are currently struggling with austerity, staff-mix, staff shortage, increasing acuity and increasing workload among many other things.

3. Peer support as a new role in the NHS

a) Progress

Health Education England (HEE) have laid out their ambition to support the development of peer support workers nationally, and have identified opportunities to support the growth of the peer role up until 2024. They focus on peer roles across perinatal mental health, adult severe mental illnesses (SMI) community care, adult crisis alternatives and problem gambling mental health support. Their report, Stepping Forward to 2020/21: The Mental Health workforce Plan for England (HEE, 2017) outlines plans for a significant increase in peer support roles, and the Mental Health Implementation Plan 2019/20 – 2023/24 outlines the aim of training an additional 4,730 mental health peer support workers over five years.

To accompany the workforce plans described above, HEE commissioned the development of a national competency framework for peer workers (HEE, 2020). This document is designed to support the commissioning, training and development of peer worker roles in the NHS. Within the framework, HEE have outlined the expectations of the peer support worker role, the training and developmental support needs that organisations must take into account. They emphasise that work is needed to translate the framework into different mental health settings, and that the competencies themselves should not be seen as a mandate, encouraging organisations ‘to steer away from over professionalising a role which, at its heart, is about human connection and relationships.’ (p.1)

The competency framework has the potential to provide long-sought clarity to organisations employing peer workers. It remains the case that the peer support role is sometimes confusing to teams and organisations. Since peer support is a values-based way of working, it is less easy to articulate the duties a peer worker might undertake or the wide range of skills that they may draw on. Providing a competence framework may help to frame the peer worker role in terms which employers can easily understand, and help peer workers to be accepted into roles which are within their capabilities to undertake.

In addition to the competence framework, work is also being undertaken to develop an apprenticeship pathway for peer workers. To date, the lack of academic accreditation within peer support training has preserved the accessibility of the peer worker role for applicants regardless of their previous levels of educational attainment. However, in the longer term, this can also act as a barrier to those peer workers wishing to move into more senior roles or access professional training. The apprenticeship pathway will provide an opportunity for aspiring peer workers to gain a peer support qualification whilst in employment, accredited at Level 3 allowing for academic recognition and progression and professional recognition as a distinct occupation.

Although peer support workers are included in national workforce planning, there is very little mention of peer support in current policy documents. They are generally included in lists of new roles in the NHS and in lists of the different professional groups expected to be employed. However there is nothing about their role or their distinct contribution within mental health teams – or in relation to physical health services.

b) Pitfalls

i) Practice moves faster than policy Whilst it is heartening to see the investment in peer support by HEE, their focus on particular mental health services for the first three years of funding means that other services, many of which are developing peer roles, will do so without investment, guidance or support. Peer support workers are increasingly employed in primary care teams; as link workers, social prescribers, health coaches, community navigators for people with long term conditions including mental health problems, long covid, as well as frequent attenders at GP surgeries, frequent callers of emergency services, frequent attenders at Emergency Departments. Peer support is also developing in services providing support for long term physical health conditions, for people with learning disabilities and autism, people with eating disorders, those using substance misuse services and people with mental health problems in prisons.

Moving forward

In every area where peer support is newly developing particular attention needs to be paid to how it should be offered and what people using these services tell us is helpful in these specific settings. For example, peer support is growing in forensic services, where debates about boundaries, what type of lived experience makes one a peer, and level of access/ security clearance are beginning to emerge. At the present time there are many diverse peer support projects developing in communities, across the whole range of health and social care services and thought needs to go into how to employ, train and supervise peer workers for different settings. There is no forum for sharing learning, no evaluation framework to assess or compare approaches; there is a competitive culture because different groups are rivals for the same funding. We suggest that funding is made available for a national community of practice to enable us to collaborate, share progress, generate new ideas, agree leadership for new projects together and coproduce evaluation frameworks that can be used across different services. This would be a powerful way of sharing learning, one of the cornerstones of peer support, and enable areas where peer support is in its infancy to learn from the successes and challenges of more developed projects.

ii) Co-option

The HEE competence framework has been a controversial development within the peer support community. National Service User Survivor Network (NSUN) have stated that ‘the Competence Framework is a product of deeply flawed processes and, as such, a lot of its content is problematic. The wider issue here is who led the Competence Framework – and this, our key demand, was not up for negotiation’ (Hart, 2020). The development of such a framework has magnified debates surrounding ownership and co-option in peer support. These debates have been live for as long as peer workers have been employed in statutory mental health services, but with the current expansion of peer support and the development of frameworks and pathways, often without adequate involvement of people with lived experience themselves, they take on a new urgency.

Many believe that peer support may be misused within mental health services, so that peer workers will be expected to conform to the practices that the survivor movement continues to campaign against. While some have welcomed the introduction of peer workers as a sign that cultures are becoming more open to valuing lived experience, others have viewed it as ‘co-option’ or misuse of survivor knowledge to serve mental health systems, while they leave their controlling practices intact (Penney & Prescot, 2016). Voronka (2017) questions: ‘to what effect are we [peer workers] deploying our work to orient clients toward feelings and responses that actually encourage compliance and cooperation with dominant conceptual models of mental illness?’ (p. 335). Many survivors have questioned how possible it is to maintain the mutual philosophy of peer support within highly structured organisations such as the NHS (Faulkner, 2020).

All too often, projects employ people with relevant lived experience to deliver professionally developed interventions, rather than to draw on experiential knowledge to support and empower people to make their own decisions about how to manage their condition, their treatment and their lives as a whole. In addition, debates remain about how the peer worker role should be used in conjunction with risk assessments, medication and physical restraint, with some peer workers seeing these as tasks that they support within their role and others believing these to be philosophically at odds with their values base.

Moving forward

In their HEE thought piece, Ball and Skinner (2021) describe how the debates about ownership and co-option within peer support can imply that peer support workers in particular settings such as the NHS deserve estrangement and alienation from the broader peer support community external to statutory organisations, because the support they offer is less ‘pure’. They, and others, have argued that rather than viewing peer support in statutory services as inferior or compromised, it should be acknowledged as an equally legitimate form of peer support in what is a broad spectrum of approaches. We too believe that peer support is essential within statutory services; the presence of peer workers to offer support when people are at their least empowered within mental health systems is a huge achievement, that has been long campaigned for. Of course, this only remains an achievement if peer workers are trained with an awareness of the activist roots of their role, if they are supported to uphold the values of their ‘profession’ and if there is leadership and strategy in place to provide a structure for progression and ongoing development. These points are discussed further below.

iii) The experience of peer workers in health and social care systems

Despite the role of peer workers becoming ever more recognised, there is a huge body of literature which testifies to the difficulty experienced by peer workers working within mental health systems. The narratives of peer support workers consistently emphasise themes of feeling stigmatised by other staff, being viewed through a diagnostic lens, experiencing poor support structures, a lack of credibility in peer support and unclear working roles. While many of these poor experiences relate to the ongoing stigma attached to the peer (service user) identity, there are also testimonies of the difficulty of adopting any new role in the context of over-stretched, under-funded mental health systems where there never seems to be enough time to properly think about how best to harness the strengths of the workforce.

These working environments, coupled with the desire to uphold the values of peer support can create profound professional dissonance among peer support workers. The sense of being unsupported within a system which does not subscribe to the values of peer support is exacerbated by the lack of strategy or structure within these systems to support peer support workers. Currently, there is no nationally established career structure for peer support workers and there is little peer leadership. Most peer support workers are managed and supervised by health professionals rather than leaders in peer roles.

Some organisations are appointing experts by experience to lead coproduction and service user engagement and to sit on boards and senior decision-making committees. This is all done without any explicit clarity or agreement about the distinct knowledge that lived experience brings, the value that it adds, or the reason why it is sought. As numbers of peer workers are set to swell, there is a risk of more and more organisations employing and training peer workers without a clear understanding of the reasons for doing so. This will only add to the poor experience of peer workers within these systems, who may begin to adopt traditional ways of working to fit in with their professional colleagues, or may feel isolated in their values base without support from a wider team and culture.

Moving forward

Mental health organisations with greatest success in employing peer workers are those that are already committed to shifting the culture of services to be more focused on enabling people using services to recover and live well in their communities. As part of this they have a clear understanding of the importance and value of the lived and life experience of all staff, and are actively developing practices that empower people using services through shared decision making and coproduction at every level. It is increasingly challenging to maintain momentum in this movement as staff shortages and continual changes in structures and processes place almost impossible demands on front line providers. Where teams are well prepared for peer workers they recognise the value and contribution that they can make to the experience of people using services and take steps to enable them to build mutually supportive relationships. There is, however, in all services, a notable lack of peer leadership for the peer workforce and no agreement about the role of peer leaders as another professional lead at senior management level, this is discussed in the following section.

iv) Peer leadership and career progression

The progress that has been made in developing peer support workers within mental health services has largely been led by professional groups, and those who identify in other ways than through their lived experience. It has taken these people in positions of power to ‘sell’ peer support, their voices carrying more authority than those of people using services within many statutory service contexts. While this has undoubtably led to progress, the lack of people with lived experience leading the direction and vision for peer support has impacted (impaired) the course that developments have taken at a national level and within organisations. There now exist many peer support workers with many years of experience of working within services. These peers remain within the positions they were first recruited to, as few organisations are employing peer workers in leadership posts. It is difficult not to see this as an indication of the low trust and value placed in peer support workers nationally.

One of the key criticisms levelled at the HEE competency framework is that people with lived experience were not able to own, or even co-lead on, its development. Price (2020) argues that this has resulted in a framework which creates a version of peer support that conforms with the existing NHS ideology, based in clinical knowledge and treatment pathways. Both at a national and local level, the establishment of peer leader roles, and a clear route for progression for peer workers which does not entail joining an existing profession such as nursing, is vital in preserving the identity and integrity of peer support in health and social care.

Peer leadership roles have been created by some NHS and social care organisations. Sometimes these posts are paid at the same level as other service managers, and sometimes the job descriptions, which lack a professional registration, are matched at a lower level because lived experience is not valued in the same way as professional expertise. Peer leaders have reported having little support in the face of unrealistic expectations about their role and a need to present themselves as credible and competent in sceptical systems (NSUN & Mind, 2021). They have also described feeling attacked from within their peer communities, partly because the nature of peer leadership is still up for debate, but also because of the perceived compromises involved in working in senior positions within statutory organisations. These conditions have led to peer leadership roles often coming with a personal cost to those employed within them. Of course, when peer leadership roles have been created, it is with quite the opposite intention to this: often they are created with the hope of embedding a wider vision for recovery orientated change across services. However, especially in the context of ongoing austerity, recovery focused practices have struggled to occupy a central position in the prevailing socio-cultural practices of mental health organisations.

Moving forward

The challenge of changing cultures is often one of the expectations of peer support workers, who generally occupy one of the lowest paid roles in mental health organisations. A peer support leadership structure, where lived experience is valued as an equally legitimate form of knowledge as professional expertise, would be a true sign of culture change. Just as other professionals have a professional lead, peer support workers need leadership to continually clarify their distinct contribution to services; to consistently articulate the difference that they make to the experience of people using services; to work with other staff to prioritise the voice and experience of people using services and to promote peer approaches at all levels of services. Further to this, there needs to be support for peer support workers to develop their skills as leaders and this development must be rooted in the experience and expertise of grassroots peer support and activism rather than in professionally informed health service leadership that exists in different paradigms and practices. Indeed, peer leaders need to develop the skills to work across boundaries and beliefs, to practice co-productively and to remain faithful to peer values. Without this, the employment of peer leaders risks being tokenistic and will not bring about meaningful culture change.

v) Cultural competence and diversity with peer support

Socially excluded communities, which experience the poorest health outcomes, are over-represented in mental health services and under-represented in formalised peer support. Although peer support has long existed in marginalised communities, the concept of lived experience in workforce plans often fails to take into account the multiple different kinds of lived experience a person has, including the experiences of racism, sexism, heterosexism, oppression and discrimination and their intersection. The word ‘peer’ is increasingly used to describe a person with lived experience of mental health challenges, while failing to take into account the other qualities that make us peers to each other.

Some have referred to this filtering of the peer concept as a form of ‘strategic essentialism’; uniting under our shared characteristics to bring about social change. This can be a powerful tactic for collective change, however it may also serve to reinforce the stigma associated with the experience of mental distress, by failing to consider the other, equally important, elements of a person’s being.

Faulkner and Kalathil (2012) found that for many people, the shared experience of mental distress is not enough to identify with someone else as a peer. Their report surveyed people from a diverse range of peer support projects and found that more than half of the respondents said that peers should share characteristics including gender, ethnic background, sexual orientation, age, religion and faith. Sixty-six per cent of respondents from BME communities felt that a shared ethnic and cultural background would be important in a peer.

The HEE benchmarking report (2020) found that 84% of peer workers were White or White British, a population which had some of the lowest rates of detention under the mental health act between 2019-20 (NHS digital, 2021). This is clearly a failure to adequately consider what diversity in peer support actually means, and how it can be supported. It is an alarming thought that peer support within statutory mental health settings is being distorted by the institutional racism inherent within these services, but we must collectively, repeatedly guard against such a future unfolding.

Moving forward

There is no straightforward way of addressing systemic racism. It takes active and continued work on every level, using a wide range of approaches. A starting point would be to actively recruit peer workers from diverse communities, and aim to recruit peer workers who reflect the diversity of the people they will be supporting. Peer support training should always be offered within a human rights based frame, given the history of the survivor movement, but it is essential that this also includes a broader understanding of inequality and oppression to account for the intersectionality experienced by many using health services.

The most meaningful way of addressing these issues is to step back and listen to the people who are most affected by them. We need to actively seek out the voices that we have marginalised and listen to what they have to say. Much of the recovery movement has been characterised by co-production, and this must continue within peer support, so that we may consider diversity within the peer support population a source of pride, and not of failure.

Recommendations

In order to provide the most beneficial environment for the next stage of peer support, we suggest that the focus needs to develop rapidly from the current focus on training peer support workers to focused consideration of the cultural and systemic contexts in which they work. With this in mind, we suggest that the following considerations are essential:

1. Strategy both at an organisational and national level to enable infrastructures that support the introduction of peer support into the workforce as part of current transformations.

2. Peer Leadership, also at an organisational and national level, with meaningful and supported peer leadership roles at every level of services. This should include the development opportunities to enable progression into peer leadership roles within mental health services. Peer leaders need to recognise the roots of peer support and be enabled to speak from these roots to support wider cultural change.

3. Reuniting with the roots of peer support

4. Critical focus on diversity and inclusion in the development, delivery and reach of peer support.

5. Peer support co-ordinated at a locality level with all services that offer peer support.

1. BEYOND TRAINING AND EMPLOYMENT: INFRASTRUCTURE AND STRATEGY IN HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE SERVICES

The peer support competency framework commissioned by HEE has provided a foundation for training peer support workers and as a result, large numbers of peer workers are completing the training ready for work. For those wishing to work in NHS and social care services, there are two challenges: first, securing a job; second, sustaining a peer identity and role within their job so that they can bring added value to existing services. Peer workers themselves have limited control over either of these challenges, responsibility lies mainly with the organisations within which they work.

We have previously written extensively about the importance of organisational support the wide- ranging commitment that is necessary for successful employment of peer workers (Repper et al., 2013). This remains the key to maximising the impact of peer support on those with whom they work and on the culture of services, enabling them to thrive in work and utilise their experience and skills as a distinct and complementary occupation. To build on the existing published best practice for supporting peer workers, we suggest that the coming decade requires the following:

Coproducing organisational understanding of peer support

Although work with individual teams might improve the day to day work experience and impact of peer support workers, we need to recognise the importance of whole organisation commitment to peer support workers if they are to realise their full potential. Peer support is only one aspect of the cultural change that is needed for services to become truly focused on the Recovery of people using services (see ten organisational challenges; Shepherd et al., 2010). But in itself it is an effective vehicle for effecting that cultural change: the collective voice of peer support workers and staff with lived experience is invaluable in informing, modelling and coproducing services and practices that are person centred, Recovery focused and support people to live well in their communities.

Organisations wishing to employ peer support workers need to demonstrate their commitment to peer support and the value they afford lived experience in all their staff if their commitment to peer support workers is to carry any credibility. The free of charge peer support training currently offered by HEE brings with it a grant attached to each student which is intended for infra-structure support and to enable trainees to complete the training. However, this can also provide a perverse incentive for organisations to

send peer staff (or potential peer staff) to the training, reaping significant financial reward but never developing their organisational

or workforce strategy for peer workers, nor addressing the cultural barriers to effective peer support. By contrast organisations that invest in coproducing a peer worker strategy that includes all levels, professions and departments begin to see how peer support workers offer solutions to many of the challenges currently facing them. Given the evidence that people using services value their relationships with peer support workers for increasing their hope, self confidence and self efficacy (Corrigan, 2006; Ochocka et al., 2006; Salzer, 2002), shouldn’t everyone have the opportunity to receive peer support? Since peer support workers are associated with reduced levels of restraint on inpatient wards (SAMSHA, 2010), we need to work out how to utilise their approach more widely to improve the experience of people using services. We have a number of long standing vacancies, would it be possible to improve the service offered by making these peer support worker posts? We have a number of new teams created through the new transformation plans which require peer support workers, how are we going to recruit and support peer workers in these posts, and what will their role be? Such questions clarify the importance of including peer support workers in Workforce Strategy with clarity about role, job descriptions, banding, supervision and management.

Frequently, coproducing a peer support strategy raises wide-ranging questions about culture and practice: surely what is good employment practice for peer support workers is good for all staff? So, what about proactive employment support for everyone? Should all teams use staff wellbeing plans? Isn’t Recovery focused supervision using the co-reflective approach of peer support an improvement on current supervision practice? Why are we worried about peer support workers hearing staff talking about patients? Maybe we need to mindful of how we talk and write about people? Don’t we all need to know more about trauma informed relationships? How are we going to enable all staff to use their personal experience safely and appropriately in their practice? …. These discussions drive forward changes across the whole organisation – in HR and workforce planning, in Learning and Development and staff training, in documentation and record keeping.

Preparing and supporting teams with peer support workers

Extensive research demonstrates that peer support workers need to be absolutely clear about their role within the team, and other staff and people using the team’s services also need to be clear about why peer workers are being employed, what their role is, how they have been trained and the fact that their employment contract is the same as other staff – they are a member of the staff team, not a patient or a member of staff who needs special support or who cannot be trusted. The kind of support available for peer workers is available for all staff (many of whom will also have lived experience of mental health problems, but they are not employed to use this as their primary point of reference). Team preparation is essential for clarity about the role and contribution of peer workers in the team (see Repper, 2013).

A one-off workshop with teams prior to the employment of peer workers is necessary but not sufficient. Too often the culture of teams that are short staffed, continually responding to crises, implementing changes in structure as policy dictates, coping with rapid staff turnover … is reactive, rushed, problem focused and risk averse. This is in stark contrast to the expectations and training of all staff, but perhaps it is most marked in relation to the role of peer support workers. Their training focuses entirely on using their own personal experience to enable safe, trauma informed, non-judgmental relationships in which the people they support have space to make sense of what has happened and work out what might help them. Given the time and opportunity to work in this way, peer workers offer hope that things can get better, they help build self confidence and reduce shame and self stigmatisation, they can support people to re-engage in communities, activities and relationships. Where this sort of work is not valued, peer support workers all too easily conform to the routine practices of the team – or they can resist and this quickly leads to burn out. Not only do teams benefit from ongoing support to maintain and develop their peer support workers, but the peer support workers themselves require regular, recovery focused supervision.

A national strategy to underpin the development of peer support

It is not a new idea to talk about organisational strategies for peer support workers, or about preparing the mental health workforce to support the development of peer support. While it is becoming more and more commonplace to acknowledge the importance of peer support at these organisational levels, what is lacking, and what is now needed, is a national strategy for peer workers.

As HEE continue to invest in the development of peer training and support the growth of the peer workforce across some health contexts, there needs to be much more consideration of a bigger picture. A national strategy needs to lay out answers to key questions, including, why we are growing the peer workforce, how this is best done without compromising the values of the approach, how organisations can start, what we know about best practice and what success looks like in employing and supporting peer workers.

This national strategy needs to be written and owned by peer workers and people with lived experience, and not professional bodies or departments. Failing to do this would result in further co-option of peer support and would only offer a vision for peer support which supports existing ideologies rather than a vision which might offer radical challenge to these, as peer support has always intended to do.

To support the development of this strategy, there needs to be well positioned peer leaders, including a peer support lead within the Department of Health, with a team around them who can amplify the collective voice of peer workers and advocate for the complex needs of this diverse group of people.

In addition, the development of national peer support forums for peer workers is long overdue. While other mental health roles have access to a professional body, external support, literature specific to their role and development/peer support opportunities, peer workers do not. Some forums of course exist, and local initiatives have led to the establishment of peer support collectives, but with further consideration to the national development of peer support, this can be offered to every peer worker, including those who are isolated in their role or in their organisations. These forums should offer a place for peer workers to support and learn from each other, but also to speak about national developments and to inform the course of peer support at a broader level. Without such platforms, peer workers will be unable to foster a sense of their collective power, and will be more likely to find themselves at the mercy of the psychiatric/ medical systems that employ them.

2. PEER LEADERS FOR THE PEER WORKFORCE

Lack of career progression and low pay among peer workers are examples of structural powerlessness; while peer workers may have a sense of their own power within peer support relationships, and may be valued within their teams, there needs to be a greater commitment to embedding peer leadership structures within organisations in order to truly value people with lived experience. To enable meaningful peer leadership within mental health systems, there must be posts available for peer leaders to take up, and there must be support, training and mentorship for peer workers to progress into these roles with the required skill set. In relation to these needs, the following factors should be considered:

– Peer leader roles must be continuously funded and not short-term contracts. Relating to the points made on peer worker strategy, short term funding undervalues peer workers in a symbolic and actual way. Peer leaders require time and stability in their role to make effective change and

this is not possible on short term contracts, even where these are likely to be extended

– The peer leader job description should be robust, written to meet the needs of the peer workforce, and to support the organisation to welcome and nurture lived experience in their staff mix. It should include any requirements that are thought to be needed relating to additional training, project/people management and supervision skills. The job description should be taken to job evaluation panels with supporting information which describes the national context of peer support, and the value of lived expertise as equal to professional knowledge. On occasion, the lack of professional registration and other elements such as not being a budget holder, has led peer leader job descriptions to be banded as lower than the colleagues that peer leaders work alongside. This does nothing to empower peer leaders, but also does not acknowledge the actual demands of their role.

– Peer leaders should not be employed in isolation; there needs to be a community or team of senior peers who support and work alongside each other. The employment of a single peer leader is, at worst, tokenistic, and does not recognise the size of the task of peer support implementation and culture change.

– As with any role, peer leaders need role clarity; the beauty of peer support is that the values can influence all other organisational agendas, including least restrictive practice, involvement, service developments, trauma informed care and staff wellbeing to name a few. There is a temptation for peer leaders to become involved in all of these agendas out of a desire to support widespread culture change. However, with limited resources, this dilutes what peer leaders are able to offer to the peer workforce. There needs to be clear expectations about how much of a peer leader’s time can helpfully be used for projects outside of peer support

– There should be strategic consideration of how a peer support worker might progress through different levels of the organisation, perhaps into a senior peer role and then into a central peer support development role, and then as a peer leader. The use of an apprenticeship pathway might support this depending on how organisations choose to position this (for some, the apprenticeship might be an entry level requirement, for others it might be required for peer workers to progress into a senior peer role). Other pathways should also be available for peer workers where the apprenticeship is not suitable. Supervision and peer trainer training, as well as development opportunities and work experience should be offered to all peer workers.

– There should also be training focussed specifically on leadership skills. This should not be generic leadership training; the skills required to be a peer leader are complex and require applying the values used within peer support relationships to an organisational setting. The role of peer leaders to challenge and influence culture can feel like a heavy task. Training should include practical approaches to positively challenge within a clear context of the roots of peer support. Education on the history of the survivor movement and the associated philosophy is essential to support peer leaders to retain a clear sense of purpose and to understand the importance of the values of peer support to the organisations they work in

– Peer leaders require ongoing support both from colleagues within their organisation and from fellow peer leaders. Developing strong working relationships with peer leaders from other organisations, including user led, voluntary and grass roots projects can provide peer support to leaders, to help them to feel supported by a collective, and to ensure that their peer identity is not stifled by their organisational setting

3. REUNITING WITH THE ROOTS OF PEER SUPPORT

‘It is a difficult task to make recovery and peer support centrally relevant to mental health organisations in times of austerity without their original intentions being subverted and co-opted. It is only in the process of constant resistance, revisiting and reframing of the way that peer support is offered that we can preserve its radical intentions.’

(Watson, 2020, p.280)

As we outlined above, the inclusion of peer support workers into statutory mental health services has been controversial for many lived experience campaigners who argue that mutuality cannot be sustained within these settings. As the ‘recovery movement’ has become a ‘recovery model’, which can be further broken down into ‘recovery interventions’, many of

the radical intentions of peer support have been smoothed or lost. These arguments have been enough for many critics to abandon hope for peer support within NHS services. However, to frame peer support as co-opted, and peer support workers as disempowered would be to ignore the ways that peer workers resist and challenge the systems they work in.

It is less important to debate whether or not peer support has been co-opted than it is to acknowledge that the nature of peer support within mental health services is something different (and not worse or better) than the nature of peer support outside of these. Peer workers are changed by the contexts they work within, and do often feel disempowered within these, but they also resist and subvert these cultures, and they can be more effective at doing this with the right support. Peer workers are largely unanimous in their belief that the culture of mental health services needs to change, and often enact all the power at their disposal in order to both be a part of the positive changes they believe are necessary, and to protect themselves from cultures which they believe would compromise their values base.

While the resistance of individual peer workers is clear, what is less clear is a strategic resistance, and this is what is needed to continue to move in a direction of culture change. To enhance the possibility of peer workers contributing to culture change, there are some pre-conditions that support this:

– Alliances between organisations using different approaches to peer support. To see these as opportunities to learn rather than to compare different types of peer support and find some inferior. Seeing the differences as a symptom of the context that peer workers work within, and an essential means of peer workers surviving in those contexts

– Organisational cultures that genuinely welcome challenge, and peer workers that can offer positive challenge and practical solutions rather than solely criticism

– Support for peer workers who do struggle to work within systems which leave them feeling compromised, in the form of supervision and peer to peer co-reflection from peers within and outside the systems they work in

We should all be prepared to challenge existing practice where we see that it could be improved, but the impact that austerity, understaffing and service change has on working practices and staff wellbeing should also be acknowledged. Many peer workers have spoken out of concern for their

colleagues who they described as also undervalued and struggling to cope in their roles. True culture change requires us to collectively, repeatedly highlight the unacceptable demand placed on mental health services

4. CRITICAL FOCUS ON DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

Now is the time for the inclusive value of peer support to be truly realised. Inclusivity needs to be re-politicised, and the focus should shift toward the circumstances and groups which create exclusion. The following approaches support the development of peer support which reflects the diverse communities that peer workers serve, and ensures that people using mental health services are offered peer support by those they truly consider to be their peers:

– Partnerships should be built between mental health organisations and peer support providers within social excluded communities including refugees, LGBT, BME, service user-led groups and be inclusive of the experience of many different stories of recovery and intersectionality. The peer support offered by these communities should be valued and inform the implementation of peer support within organisations

– Peer support strategy should clearly communicate a broad definition of lived experience, which acknowledges the impact of multiple oppressions on mental health and recovery

– Any peer support co-production/ implementation groups should include people from socially excluded communities

– Peer support and peer leadership training should include an appreciation of intersectionality, institutional racism and anti-racism. The use of safe spaces should be considered when covering these topics

– Where peer support roles at any level are advertised, adverts should be circulated within socially excluded communities and should consider their use of language to minimise the barriers to people from these groups applying

5. PEER SUPPORT CO ORDINATED AT A LOCALITY LEVEL WITH ALL SERVICES THAT OFFER PEER SUPPORT

In line with the long term plan and community transformation, we are increasingly working across localities and communities in an integrated manner: all health and social care services are working with Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) providers, mainstream facilities and activities to offer clear pathways of support within a defined locality. Peer support in all its guises has an important role to play in this: in prevention, primary care, community navigation, specialist services and longer-term community based support. It makes sense for people and organisations offering peer support to come together: to share learning about how best to support people, to find out more about each other so that those using these services can access other relevant support; to establish pathways and clarify roles and relevant expertise, to make their services and their successes better understood so that they are valued and funded. The shift from a competitive to a collaborative peer support alliance at a locality level, represented at integrated care boards, included at ICP and PCN levels, clear about which peer organisation/team is best placed for what provides better support for individuals needing it, wider opportunities for peers offering it, and more likelihood of greater understanding of the value that peer support can offer at individual, community and societal levels.

A VISION FOR THE FUTURE

The next decade of peer support development requires us to progress beyond focussing on the introduction of peer workers. The training, development and supervision that is most helpful for peer workers requires us to shift our focus onto the systems that surround them, in order to create conditions in which peer workers can thrive. In addition, peer leadership and career progression for peer workers is essential and there needs to be many more senior roles for peer workers. This would demonstrate that lived experience is genuinely valued in a similar way to professional expertise. Peer workers positioned at all levels throughout our health and social care systems begins to shift the dominant narratives about mental health, and provides us all with examples of recovery, embodied by people who bring their lived experience and a range of other leadership and culture change skills to the table. Changes of this kind require health systems and society to address discrimination in all its forms, and to hold a vision of a radically different future in mind. We can offer such a vision.

Imagine if the next ten years of peer support contained as much change and growth as the previous ten. In the next decade, it might be possible for any person who requires the support of health or social care services to be met by people who had shared lived and cultural experience, who could offer emotionally safe relationships where power is relatively balanced. Peer support should be available to any person regardless of the service they find themselves using, and it should be offered by people who reflect the diversity of the people using each service.

The systems that peer workers are employed within will welcome peer support as a new occupation and there will be clear strategies in place that describe how peer workers should be supported, how the workforce will grow, and why peer support will benefit teams and systems. These strategies will highlight the need for a diverse peer workforce and acknowledge that part of the peer worker role is to positively challenge mental health cultures. Clarity over how the HEE training grant attached to each student is used will ensure that people with lived experience, who are ready for peer work are able to access the peer support training to support their move into peer support roles.

For those of us wishing to become peer workers, the future will be empowering. There will be ways to become involved in shaping services and ways to access peer support training and employment support. At no point in the journey to becoming a peer worker should a person feel stigmatised

or unwelcomed within health and social care services, not least because they will be surrounded by other peer workers, and offered co-reflection by peer leaders. There will also be opportunities to link into nation-wide networks of peer workers to seek support, learn from each other and shape the future direction of the role. Organisations will value lived experience as an important asset that supports culture change; peer leaders, positioned at all levels of the health and social care system will hold a vision for peer support within their organisation, and ensure that the values of peer support are translated into these contexts without being co-opted or compromised. Leaders will be offered training and mentorship, and be paid and valued in the same way as other professional leads. A professional lead at the Department of Health, supported by other peer leaders will be a good starting point for the co-production of a strategy which is owned by peer workers and people with lived experience. This will support the development of a ‘professional’ body for peer workers, one that will be able to hold the critical debates which define peer support, and amplify the voices of peer workers, even where these are complex or disparate.

We are hopeful that this future can become a reality, if we continue to shift focus away from interventions or service level change, onto culture change, diverse communities and human rights.

Conclusion

The next decade will be an era of rapid development within peer support. We have already seen an increased recognition of the value of lived experience informing the development, delivery and evaluation of all services. As peer worker numbers grow, particular attention should be paid to ensuring that their growth is supported, and their inclusion into the workforce is meaningful. Peer support workers bring a particular and distinct form of support, underpinned by a clear values base. They model a different way of ‘being’ with people that supports the self confidence, self efficacy, hope and essential for living well. The experience of feeling safely supported by a peer should not be under-estimated; everybody should be offered the opportunity to access this support in times of distress and when managing long term conditions.

We are still early in the journey of introducing peer support, and the diversity of thought within peer support communities means that several debates continue to be had. How exactly peer leaders should operate, how to maintain the values of peer support in struggling systems and how to ensure peer workers are able to both challenge and support their colleagues within services are critical discussions. As the next decade of peer support unfolds, it is important to continue to revisit and reflect on the debates surrounding peer support and to establish some national infrastructure to support the development of this new sphere of the health workforce. This paper is by no means a definitive ‘answer’ to the current pitfalls, but we hope to have offered some possible solutions, particularly for those organisations whose task is to implement the Long Term Plan, and wish to do so in a meaningful, sustained way. By moving the focus back onto organisational cultures, we hope that the conditions will be provided to enable peer support, in all its diverse forms, to take flight.

References

Ball, M. & Skinner, S. (2021). Raising the glass ceiling: considering a career pathway for peer support workers. Retrieved from: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/ files/documents/Raising%20the%20glass%20ceiling_ considering%20a%20career%20pathway%20for%20 peer%20support%20workers%20-%20Final%20%281%29.pdf

Bellamy, C., Schmutte, T., & Davidson, L. (2017). An update on the growing evidence base for peer support. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21, 161–167.

Blanch, A., Filson, B., Penney, D., Cave, C. (2012) Engaging women in trauma informed peer support. National Center for Trauma-Informed Care.

Chamberlin, J. (1978). On our own: Patient-controlled alternatives to the mental health system. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Corrigan, P. W. (2006). Impact of consumer-operated services on empowerment and recovery of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 57, 1493–1496.

Faulkner, A. & Kalathil, J. (2012). The freedom to be, the chance to dream: Preserving user-led peer support in mental health. London, UK: Together for Mental Wellbeing.

Faulkner, A. (2020) The Inconvenient Complications of Peer Support’. NSUN Blog. Retrieved from: https://www.nsun. org.uk/Blog/the-inconvenient-complications-of-peer-support- part-2

Faulkner, A. (2021). Principled Ways of Working: Peer Support in Sussex. NSUN Report. Retrieved from: https:// www.nsun.org.uk/resource/principled-ways-of-working-peer- support-in-sussex/

Filson, B. & Mead, S. (2016). Becoming part of each other’s narratives: Intentional peer support. In J. Russo & A. Sweeney (Eds.), Searching for a rose garden: Challenging psychiatry, fostering mad studies (pp. 109-117.). Monmouth, UK: PCCS Books for Mental Health Peer Support Workers. Retrieved from: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/ documents/The%20Competence%20Framework%20 for%20MH%20PSWs%20-%20Part%202%20-%20Full%20 listing%20of%20the%20competences.pdf

Gillard, S., Gibson, S. L., Holley, J., & Lucock, M. (2015a). Developing a change model for peer worker interventions in mental health services: A qualitative research study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24, 435-445.

Gillard, S., Holley, J., Gibson, S., Larsen, J., Lucock, M., Oborn, E. . . Stamou, E. (2015b). Introducing new peer worker roles into mental health services in England: Comparative case study research across a range of organisational contexts. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 682-694.

Health Education England (2020) National Workforce Stocktake of Mental Health Peer Support Workers in NHS Trusts. Retrieved from: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/ files/documents/NHS%20Peer%20Support%20Worker%20 Benchmarking%20report.pdf

Health Education England. (2017). Stepping forward to 2020/21: The mental health workforce plan for England. Leeds, UK: HEE.

Health Education England. (2020). The Competence Framework

Mead, S. & Macneil, C. (2004). Peer Support: What makes it unique? Retrieved from: http://www.Intentionalpeersupport.org/articles/

NHS Digital. (2021). Detentions under the mental health act. Retrieved from: Detentions under the Mental Health Act – GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures (ethnicity-facts-figures. service.gov.uk)

NSUN & Mind. (2021). Lived Experience Leadership – Mapping the Lived Experience Landscape in Mental Health. Retrieved from: https://www.nsun.org.uk/resource/lived- experience-leadership/

NSUN. (2019). Peer support Charter. Retrieved from: https:// www.nsun.org.uk/resource/peer-support-charter/

Ochocka, J., Nelson, G., Janzen, R., & Trainor, J. (2006). A longitudinal study of mental health consumer/survivor initiatives: Part 3 – A qualitative study of impacts of participation on new members. Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 273–283.

Penney, D. & Prescot, L. (2016). The co-optation of survivor knowledge: The danger of substituted values and voices. In J. Russo & A. Sweeney (Eds.), Searching for a rose garden: Challenging psychiatry, fostering mad studies (pp. 35–45). Monmouth, UK: PCCS Books.

Price, V. (2020). Mental Health Peer Support Worker Competence Framework: A Personal & Professional Reflection. NSUN Blog. Retrieved from: https://www.nsun. org.uk/mental-health-peer-support-worker-competence- framework-a-personal-professional-reflection/

Repper, J. (2013). PSWs: Theory and practice. London, UK: ImROC and Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

Repper, J., Walker, L. (2019) Peer Support for People with Physical Health Conditions. ImROC Briefing Paper 18. Nottingham, ImROC

Salzer, M. S. & Mental Health Association of Southeastern Pennsylvania Best Practices Team. (2002). Consumer- delivered services as a best practice in mental health care and the development of practice guidelines. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills, 6, 355–382.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2010). Promoting Alternatives to the Use of Seclusion and Restraint—Issue brief #1: A National Strategy to Prevent Seclusion and Restraint in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Shepherd, G., Boardman, J., & Burns, M. (2010). Implementing recovery. A methodology for organisation change. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

Slade M, McDaid D, Shepherd G, Williams S, Repper J (2017) Recovery: the Business case. ImROC Briefing Paper 14. Nottingham: ImROC

Voronka, J. (2017). Turning mad knowledge into affective labor: The case of the peer support worker. American Quarterly, 69, 333–338.

Watson, E. (2019). What is peer support? History, evidence and values. In E. Watson & S. Meddings (Eds.) Peer support in mental health. London, UK: Red Globe Press.

Watson, E. (2020). ‘The system is mad making’: peer support and the institutional context of an NHS mental health service (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham).

Watson, E., (2017). The mechanisms underpinning peer support: a literature review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(6) 1-12.