People in forensic (or secure) mental health services should be offered support that helps them in their personal recovery journeys.

This paper finds that recovery for people in forensic services is in most ways the same as for those using other mental health services. Hope for the future, control over your life and illness, andopportunity for a life beyond illness are key for both. But people with offending histories also have to come to terms with what they have done. Forensic services can help them to recover by supporting them to ‘come to terms with themselves’.

Gerard Drennan and James Wooldridge together with Anne Aiyegbusi, Debbie Alred, Joe Ayres, Richard Barker, Sally Carr, Helen Eunson, Hilary Lomas, Estelle Moore, Debbie Stanton & Geoff Shepherd

To View the ImROC 4th Annual Conference Presentation (Realities and Possibilities for Recovery – focused Practice in Secure Settings) click here

10. Making Recovery a Reality in Forensic Settings

Gerard Drennan and James Wooldridge together with Anne Aiyegbusi, Debbie Alred, Joe Ayres, Richard Barker, Sally Carr, Helen Eunson, Hilary Lomas, Estelle Moore, Debbie Stanton & Geoff Shepherd

Introduction

Forensic settings are probably among the most difficult places to think of applying recovery principles. People in forensic services are doubly stigmatised with repeated or prolonged contact with the criminal justice system in addition to mental health problems. Many also often have a range of pre-existing social disadvantages – family problems, educational failure, poor work record, etc. – but the process of recovery is as important for them as it is for anyone else. Indeed, precisely because of their other disadvantages, recovery is, perhaps, even more important. Given all their difficulties, how can people with mental health problems and frequent contact with forensic services be expected to have positive hopes for the future? How can they achieve a sense of control over their lives and their symptoms when so many of their choices are so restricted? How they can build a life ‘beyond illness’ when faced with the toxic combination of stigma and low expectations of those around them? To some people these ambitions may seem desirable in theory, but unrealistic in practice. These are the issues which we hope to address in this paper.

Our aims are threefold. Firstly, we want to present a credible discussion of the challenges of applying the principles of recovery in forensic settings and describe how recovery values can be expressed in a meaningful, non-tokenistic, fashion. Secondly, we want to address the implications of these challenges for staff from all disciplines and at all levels in forensic services – front-line staff, support workers, middle managers, consultant psychiatrists and senior managers. We also want to engage and involve service users and carers. Finally, we will describe current best practice within forensic services, acknowledging that not all services have achieved this, but also point towards the horizons of progressive practice within the criminal justice system and non-forensic mental health services.

A note on authorship

Advances in recovery-focused practice arise from collaborative partnerships between the people who work in mental health services and the people who use them. The ImROC briefing papers have drawn upon this work. Where ideas are taken from published materials we cite them in the conventional form, but we also want to acknowledge the many unpublished discussions and conversations that have informed the creative development of the project as a whole over the last five years.

Each paper in this series has been written by those people best placed lead on the topic. In this case it comprised a ‘collective’, who have worked together over a period of more than two years to produce this document. They believed – and continue to believe – that recovery in forensic services is not unrealistic, nor too great a challenge to meet in a meaningful way. They were helped through a series of local workshops by colleagues and partners, and service users, from forensic services up and down the country.

At each workshop the question, “What helps and what hinders recovery?” was considered across the domains of risk and safety, meaningful occupation, meaningful working relationships, and recovery outcomes. The responses of all those attending to these questions form the basis of what we are reporting here. We would particularly like to thank James Wooldridge, whose personal experience of using forensic services, intelligent reflection and general good humour, have proved invaluable to the project.

Background

In 2008, the ImROC programme produced the first of a series of papers on recovery in adult mental health services (‘Making Recovery a Reality’, Shepherd, Boardman & Slade, 2008). This spelled out the principles of recovery for a UK audience, with particular emphasis on the ways in which organisations could change to support recovery in addition to changes in staff attitudes and behaviour.

In a subsequent publication we described the development of a methodology for achieving organisational change and ways in which this could be measured (Shepherd, Boardman and Burns, 2010). This methodology has now been tested in a major national project, ‘Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change’ (ImROC) funded by the Department of Health, and delivered by a partnership between Centre for Mental Health and the Mental Health Network of the NHS Confederation (NHS Confederation/Centre for Mental Health, 2012).

‘Recovery’ refers to the personal journey of people with mental health problems as they pursue their own, unique, life goals in the presence or absence of continuing symptoms. The role of mental health professionals – and mental health services – is to try and create the right kinds of support to help people achieve these goals. This means supporting certain key principles (see Box 1). Sometimes services are successful in doing this and sometimes they are not.

Often people find the most helpful supports in their recovery are not professionals, but friends, peers and families (Davies et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the primary focus of ImROC has been upon the application of recovery principles in mainstream adult mental health services. However, these principles apply just as strongly to other client groups and to other areas of service development. In this paper our focus is on forensic mental health services.

Are ‘forensic patients’ different from other people when it comes to recovery?

Our first challenge is to examine the notion that ‘forensic patients’ have such special characteristics that recovery ideas simply cannot apply to them, e.g. “It all sounds very well, but it won’t work with these patients”. In order to examine this proposition we have created a fictional character (Jason) whose story is based on typical experiences of young men using forensic mental health services. Through the medium of Jason’s story, we aim to highlight the challenges and the opportunities for recovery. We also asked someone who has direct experience of using forensic mental health services themselves – a ‘service avoider’ (James Wooldridge) – to offer a commentary on Jason’s story.

Box 1: The key principles of Recovery (after Perkins & Repper, 2003)

- Hope – Maintaining a belief that it is still possible to pursue one’s chosen life goals. Hope is personal and relationships are central. The importance of personal meaning and understanding.

- Control – (Re)gaining a sense of control over one’s life and one’s symptoms. Having choice over the content of interventions and sources of help. Balancing evidence-based practice with personal preference.

- Opportunity – The need to build a life ‘beyond illness’. Being a part of the community (‘social inclusion’) not simply living in it. Having access to the same opportunities that exist for everyone else, e.g. with regard to housing, employment, etc.

Box 2: Jason’s story

Jason was 21 years old when he was convicted of the attempted murder of a stranger woman in an unprovoked knife attack. The attack occurred in a public place. Jason was street homeless at the time. He was arrested and, when interviewed by a psychiatrist, reported hearing voices. Jason also spoke to the doctor about being troubled by violent fantasies. He also reported abusing alcohol and self-harming and feeling, ‘completely mental’. Jason was assessed as suffering from schizo-affective disorder and an emotionally unstable personality disorder. He was not sentenced, but a transfer direction to a high secure hospital was made under a Section 37 Hospital Order (Mental Health Act, 1983) with an additional Section 41 Restriction Order. This criminal section of the Mental Health Act is imposed with no time limit, requires the approval of the Secretary of State for Justice for discharge and is imposed to protect the public from serious harm.

Jason’s story will be a familiar one to anyone who has followed media reports of high profile offences by people with a mental illness. Stranger attacks by people with mental illness are rare, but when they occur they often attract a great deal of public and media attention. For example, the case of Christopher Clunis’s fatal attack on Jonathan Zito on a Finsbury Park station platform in 1992 is considered by many to have been a watershed moment in the culture and development of forensic mental health services in England and Wales (Maden, 2007). The so-called ‘offender patient’ is usually well aware of their notoriety in local communities, even when the offences committed do not result in a death or similar such serious harm, and they are therefore faced not only with their personal struggle to come to terms with serious mental health problems and the impact of the offence, but also its social impact. In addition, they may live in fear of retribution in some form. Forensic mental health service users are therefore situated at a complex intersection of health, social and criminal justice systems.

In terms of their personal struggle, the ‘offender patient’ has a huge task to work through their personal guilt and to reconcile their ‘mental illness’ with their sense of personal responsibility (Dorkins & Adshead, 2011; Drennan & Alred, 2012; Moore & Drennan, 2013). Thus, the offending behaviour itself is often seen by the person as the greatest obstacle to their recovery. As one patient in a High Security hospital put it, “How do you recover from having killed someone?” Ideas of ‘empowerment’, ‘choice’, ‘self-determination’ and ‘participation’ can then be seen as impossible (Pouncey & Lukens, 2010). Even the promotion of hope can be seen as creating false expectation, a form of ‘double talk’ for which there is little or no evidence (Mezey & Eastman, 2009; Mezey et al., 2010).

Others have argued that, although recovery for the forensic service user has the added complications of personal guilt and social impact, nevertheless, it is still possible (Drennan & Alred, 2012). But there needs to be a focus on these complicating factors and an additional emphasis on the active tasks of finding a new identity, meaning and purpose (Ferrito et al., 2012; Simpson & Penney, 2011). In order to achieve this, the individual – and those attempting to support their recovery – need to understand as clearly as they can how the person’s life experiences brought them to the point of their offending behaviour. Returning to Jason’s story, ‘How did he get to where he was when he assaulted the unknown woman?’

Understanding the offender patient

Motivations for offending can be many and varied. Offences can be committed for psychotic, neurotic, and frankly criminal, reasons. Offences can have conscious and unconscious motivations, and usually some combination of both. People with mental illnesses and severe emotional disturbances who commit offences are also not always motivated to stop offending. Feelings of entitlement or sexual preferences can be very strong – “that’s just the way I am and no one is going to change me”. When supporting the recovery of non-forensic service users it would be strange to ask the question, “What motivated you to become ill?”, but for offenders the question of motivation is central. Taking responsibility for one’s illness thus includes an implicit acknowledgement of personal responsibility for the offence. This introduces complex scientific – as well as moral and ethical – questions for the person and the teams who work with them (Adshead, 2010; Dorkins & Adshead, 2011; Roberts, 2011; Ward, 2013). These are central to the challenges of applying recovery ideas in forensic settings.

Box 3: Jason’s early life and care in secure services

Jason had behavioural problems from a young age and was seen by mental health professionals as a child. His difficulties were assessed as being connected to his mother’s depression, a poor bond with her child, and domestic violence in the home before his father left the family. An autistic spectrum disorder was considered by professionals, but never confirmed. Jason went on to truant and run away from home. He was taken into care and placed in institutional settings and foster homes, which frequently broke down. Jason was emotionally and physically abused in care, but no sexual abuse was ever confirmed. He began to use alcohol and drugs to cope and became involved in petty crimes of survival, spending some time in Young Offender Institutions as a result. He was homeless when in the community and afraid that he would be attacked. He said he took to carrying a knife for his own protection, although it was suspected that he had developed an obsession with knives. Professionals also worried that there was a sexual element to the attack, but Jason denied this. In fact, he denied having committed the offence for a long time in hospital. Jason’s symptoms of mental illness did not respond well to medication during the first few years in hospital. After a change in medication Jason improved but he remained vulnerable to symptoms re-appearing at times of stress. He continued to be preoccupied with violent fantasies, but was reluctant to engage in any of the group and individual treatments offered to him.

Treatment and control

Treatment in forensic settings, even with psychological therapies, is often seen by patients as more coercive than in other settings. This is because the quality of the recovery achieved by the service user is not simply a question of personal choice, it is part of the imperative to reduce risk and to fulfil the duty of the service to protect the public. In other settings it may be possible to support a service user to achieve a positive sense of self, a sense of purpose, and hopefulness about the future, without being too concerned about whether the symptoms of mental illness or trauma have entirely resolved. In forensic settings, because of the link between illness and offending behaviour, this is more difficult. Sometimes it means testing the resilience of the recovery process and challenging apparent compliance where this may not be rooted in sustainable change.

Of course, there is always a difficult balance to be struck between a healthy scepticism about apparent change and a demoralising lack of belief in the possibility of personal growth. A clear-eyed view of risk and the potential for harm, while holding hope for progress towards a safe and meaningful life, is not easily achieved or maintained. However, if the presence of symptoms or emotional disturbance increase the risk of future harm to self or others, then addressing any possible link between mental health difficulties and emotional issues is not an ‘optional extra’: it must be addressed. At the same time the person must retain some sense of hope for a better life in the future.

Similarly, even when it seems that these imperatives reduce service user choice, choice remains critically important. For offenders to turn away from a life of crime they must make a choice (Maruna, 2005). Paradoxically, compulsory treatment, whether medical or arising from restrictions of movement and access can create an environment of safety in which the first steps towards recovery become possible (Mezey, et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2008). As one patient put it: “a secure hospital made me stop and let my life catch up with me”. These choices can be supported through cognitive change programmes, talking and expressive therapies. Narrative therapies can help people develop new meaning and a deeper understanding of themselves and, over time, “cover stories” can develop into an authentic account of the harm caused (Adshead, 2012a; 2012b). Hope for oneself and the future can thus be discovered (Hillbrand & Young, 2008).

‘Attachment’ and recovery

Issues of attachment are complex for forensic service users (Pfafflin & Adshead, 2004). Mainstream services may reject the importance of attachment to services and staff members for fear that it leads to unhealthy dependency and may even inhibit recovery. But many service users in secure care have personal histories of severely disrupted childhoods, through parental neglect, physical, emotional and sexual abuse, institutional care, unemployment, poverty and homelessness. These early traumatic experiences can damage people’s ability to form meaningful relationships later in life. For these reasons attachments can continue to be seen as dangerous to the self and to others and issues of ‘trust’ become central (see later on ‘relational security’). The achievement of secure and reliable attachments is therefore an on-going challenge for many people in forensic or secure care and their co-workers. It is also a central element in their recovery.

Box 4: Reflections on Jason – James Wooldridge

Reading what has been written about Jason is difficult. He has done many bad things. However, with the right support, I hope he would begin to realise that taking responsibility for his actions is a major part of his recovery. As far as I am concerned when a staff member first mentioned the word ‘recovery’ I wasn’t sure it applied to me. They said it wasn’t the same as being ‘cured’ but living the best life I can alongside my condition.

Jason had a difficult start to life and his early years were full of abuse. This has understandably left him with ‘trust issues’, making it harder to share his thoughts and feelings with professionals. If he can work with a new care team and feel that people really want to listen and to get to know the real Jason, then he will be encouraged. He needs to feel that he can influence how the assessment will read, using a language that he can understand. He also needs to review how he has often used violence to deal with stressful situations and to develop better coping strategies for dealing with stress.

For Jason – and for many people in forensic services – one of the biggest parts of ‘recovery’ is hope. People struggle with this, they know that they can’t undo the past and wonder whether society will ever forgive their crime, not to mention the victim or the victim’s family. Forgiving yourself can be a starting point but is easier said than done. It is difficult if you are struggling with violent and frightening thoughts. There is no ‘magic pill’ or ‘magic person’ that will take these away. All you can do is hope that one day you’ll be able to leave this place and carry on with your life.

For many people, the only example that will really work is someone who has ‘been there’ and can say, from their experience, that it is possible to rebuild a life outside hospital. This is vital to hear. When you’ve been locked up for a long time you begin to lose faith that you will ever get out.

From what I understand about recovery, it’s not easy. It is often one step forward and three steps back. However, going backwards for a short while isn’t always such a bad thing if you are able to learn from your mistakes and make plans not to repeat them in the future. The principles of recovery make sense, but putting them into action requires effort and motivation. I have realised that my recovery is down to me and I also know that there will be setbacks. The staff I relate to best are those that treat me as a fellow human being. One way of repaying their faith in me is for us to work together and for me to regain some control over my life.

What are the implications of a recovery-oriented approach in secure care?

We will now consider five key areas of work that can contribute to the creation of an environment in which recovery processes can take root in the men and women who become ‘forensic patients’.

Key area I: Supporting recovery along the care pathway

The process of providing recovery-focused care in secure settings is complex. There are a host of national frameworks and guidance that must influence service provision, not least of which is the Mental Health Act (1983, amended 2007) and the Criminal Justice Act. In addition, policy documents such as the NHS England Service Specifications, NICE Guidelines, the Mental Health Strategy and Implementation Framework, and many more, all aim to shape the delivery of care. Within much of this guidance, the principles of supporting recovery have become the cornerstone of good practice. These principles include:

- The importance of maintaining safety and security

- Participation of patients in all aspects of their care

- Shared decision-making, with as much transparency as possible

- Informed choices, no matter how limited by circumstances

- Fostering enabling and supportive relationships with staff, peers, family and friends (relational security).

We will now illustrate the application of these principles at key points along the care pathway in terms of their potential for helping ideas of recovery to take root and develop.

Engagement and admission

The first stage prior to actual admission into secure care is a vital first step. We can imagine Jason prior to admission to a secure hospital, perhaps in prison, acutely distressed and frightened. His first contacts with mental health service providers are crucially important points at which the possibility of recovery and hope for the future can become real – or be dashed. As indicated earlier, this depends upon people like Jason feeling that staff understand his life-story and the circumstances that led to his offending. In this way, they can foster recovery-promoting partnerships from the beginning.

Once admitted into forensic settings care is typically organised around the processes of the Care Programme Approach (CPA). This means that large multi-professional teams are responsible for assessment, planning, review and co-ordination of a range of interventions. The processes of CPA can often seem impersonal and bureaucratic to staff and to service users (Rinaldi & Watkeys, 2014). More personalised approaches such as the WRAP (Copeland, 2011), ‘My Shared Pathway’ (Ayub, Callaghan, Haque, & McCann, 2013) and the suite of toolkits in the Recovery Star (MacKeith, 2011) may be useful complements in helping the person to identify personal goals with a clear, structured approach.

Organisation of care

In terms of the organisation of care in inpatient settings, our workshops identified the following features as most important in building mutually trusting relationships and supporting recovery:

- Consistency in the delivery of supportive care – Instability and under-resourcing of clinical teams can lead to a loss of relational security, a sense of abandonment, and a reticence to engage with services. Service users are understandably upset when there are frequent changes in the care team, unsettling their progress. As one service user told us: “I’ve had five primary nurses in as many months, how does that help me?”.

- Service user participation in the design and delivery of intervention programmes – This can include participation in planning committees, co-facilitation of treatment groups, and organising unit-based activities. It can also include ward-based forums for service users and staff to discuss the daily life of a unit and the experiences of those that participate in it (such as Community Meetings, Reflective Groups, Daily Debrief Meetings).

- Service user participation in the development of policies and protocols – The design and decoration of treatment centres, catering arrangements, and a myriad other aspects of the life of the organisation are all areas where service user participation can have enormous benefits for the people whose recovery needs they seek to meet and for the safe and efficient running of the service itself (see Bowser, 2012, for a detailed description of service user participation at all levels of the organisation). Service users are now established in the Peer Review Teams for the Forensic Quality Network of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- Staff selection and appraisal – Increasingly service users are being included in staff selection, appraisal and performance reviews, including those of the most senior staff, such as consultant psychiatrists. This is a key way in which recovery principles can be used to identify service improvements at an individual and grassroots level.

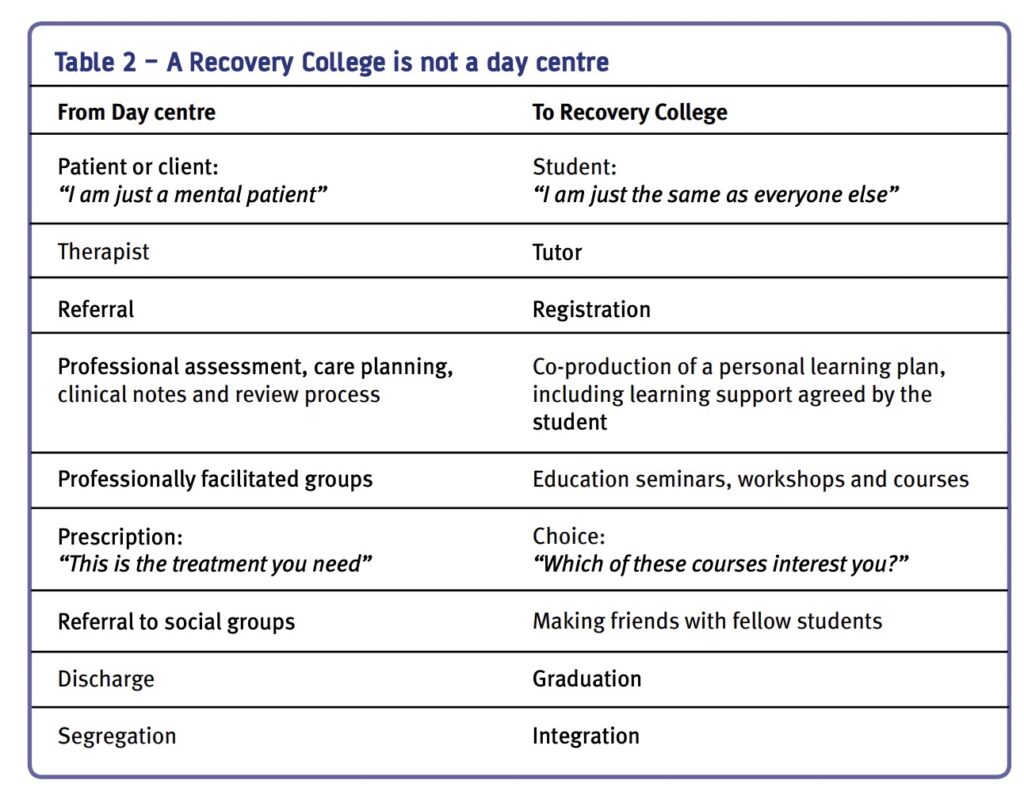

- Service user participation in staff training – Traditional approaches to staff training undoubtedly have a role in introducing staff to recovery principles (Eunson, Sambrook & Carpenter, 2012). But the advent of Recovery Colleges (Perkins, et al., 2012) has now started to pioneer a new approach to training in which service users and staff are involved as equal partners in the learning process – designing and delivering courses and learning alongside staff. These approaches are now beginning to appear in secure settings.

These principles are illustrated in the case study given below (Box 5).

Box 5: Applying recovery principles in the organisation of care – Aurora Ward, West London Mental Health Trust

A women’s 10 bed admission ward, located in a large urban forensic service, had a reputation as a ‘disturbed ward’ where the women were frequently regarded as ‘violent, chronically unwell and difficult to engage.’ The professionals of all disciplines and grades were often observed to be stressed and morale appeared low. Unsurprisingly, the ward was not a popular place to work and service user outcomes were disheartening. Following a particularly unsettled period, the decision was taken to try a new approach.

A modest financial investment was made in order to provide intensive support to implementing a recovery-oriented model of care and the services of an externally appointed Recovery Consultant were engaged to support the service in its transition. The ward leadership team was refreshed and monthly Action Learning Meetings with the Recovery Consultant were introduced. Additionally, some recovery-oriented training for the ward community was delivered, one morning per month, by a trainer from Rethink Mental Illness.

The next step consisted of a half-day team building event, combined with a halfday developing a ‘Team Recovery Implementation Plan’ (TRIP) (Repper & Perkins, 2013). This was facilitated by the external Recovery Consultant and was attended by all staff. Five areas were prioritised and a team member lead identified for each who was tasked with developing an action plan, in collaboration with service users. The priority areas were:

- Provision of examples of real-life recovery stories to inspire hope in the women and in the staff team.

- Development of recovery-oriented care plans and crisis plans, using a range of selfmanagement tools, e.g. the Recovery Star, Personal Recovery Plan, etc.

- Provision of training and education to the ward community and wider areas of the forensic services (and the Trust) co-produced by patients and ward staff. This shared their experience of implementing the recovery approach within the ward and the benefits of a hospital stay where hope, opportunity and control are emphasised.

- Promoting service user involvement in policy and procedure revisions, including a revised ‘Engagement and Observation’ policy. Inclusion of service user and carers in risk assessments.

- Providing service users with greater opportunities for choice regarding the therapeutic options provided on the unit.

The TRIP process thus provided a model for increasing collaboration between staff and patients on the ward.

As the team progressed in their journey towards implementing a recovery-oriented service to the women admitted to the ward, they increasingly began to work in partnership. Service users and staff introduced a weekly morning session on the ward where they focused on implementing the team recovery plan as a ward community. Aspects of the environment were changed to facilitate a sense of community and encourage the women to be active agents in their recovery. Service users and carers were actively involved in clinical team meetings and in Care Programme Approach meetings, with a focus on supporting service users to participate throughout their care reviews, including by chairing the meetings in some instances. A strengths-based approach was adopted, focusing on what the service users could do and not just on what they could not do. A sense of community was cultivated, through activities such as planning and preparing community meals. A sense of emotional belonging was cultivated by marking special events, birthdays, anniversaries etc with cards, messages of hope and discussions in ward-based community meetings. Likewise, endings, such as service users and staff leaving the ward, were marked as important transitions in the life of the ward community.

To support the staff team in their responses to the women’s needs, regular staff team reflective practice groups were re-instated, with the facilitation of a psychotherapist from the forensic services psychotherapy department of the Trust.

The effect on the ward was dramatic. Incidents of violence, self-harm, complaints and safeguarding referrals all decreased markedly, as did the use of seclusion. Service user progression through the ward increased which had the effect of inspiring hope regarding recovery for other. Staff morale improved and sickness and turnover of staff reduced. Importantly, staff and service users spoke of feeling proud to be part of this ward community which became a vibrant, gender-sensitive service supporting the recovery of women requiring medium secure care in keeping with the principles of the National Women’s Mental Health Strategy.

Long periods of time in secure care can feel like stagnation, even going backwards, and this is obviously damaging to hope and self-belief (Allen, 2010). Evidence of progress is therefore very important to service users and this was a key message from the workshops. People said that visible and concrete evidence of progress, “steps in the right direction” were needed, even if there were setbacks – perhaps especially if there were setbacks. Peer feedback is a defining feature of therapeutic communities in prison settings and it is interesting to note that some European countries, such as Holland, also include this as routine in secure settings. Concerns regarding confidentiality and boundaries can make this challenging in UK settings, but these are not insurmountable obstacles.

Transition to the Community

Forensic services can support individuals to develop their citizenship roles in the community by involvement with voluntary groups, work or training (see below). This will help build their confidence and support their sense of agency and recovery (Dowling & Hutchinson, 2008). Collaborations and partnerships with local art galleries, libraries, RSPCA, gyms, museums, garden centres, community football projects, conservation projects and charities have been successful in a number of settings. As well as broadening people’s horizons and giving them access to more positive social networks these opportunities also encourage the person to develop pro-social behaviours and skills in a ‘real world’ environment. Of course, they must be combined with a positive approach to risk-taking and ‘safety planning’ (Boardman & Roberts, 2014).

Key area II: The quality of relationships

“Caring is simple, but it is not necessarily easy. The young woman who cared for me was made like that – she understood what was needed and she could provide it” (Former service user, high security hospital).

As indicated earlier, the quality of relationships between service users and the staff who work with them are central to people’s recovery journeys (Slade et al., 2014). This is the case whether the encounters are very brief, or extend over many years. Recovery-promoting interactions almost always involve a degree of collaboration and some form of emotional connection or bond (Martin et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2002). These are shaped by the specific characteristics of the ward or unit and the overall culture of the organisation. Recent inquiry reports have examined the culture of organisations where basic care has gone wrong (e.g. Francis Report, 2013). They focused attention on the importance of compassion, consideration and commitment in the delivery of care.

A recovery-oriented service that has a focus on the quality of relationships will need to offer a range of staff supports, such as clinical supervision groups, team reflective practice, and individual supervision, to promote reflective thinking and adaptation by staff in relation to the challenges that arise (Adshead, 2010; Aiyegbusi & Clarke-Moore, 2008; Aiyegbusi & Kelly, 2012; Bartlett & McGauley, 2010; Moore, 2012).

“It helps me when I see positive dynamics in the staff team; the right people doing the right job.” (Former service user, medium secure unit)

Forming a supportive, professional relationship takes time, perseverance and skill. Sometimes it involves just being ‘ordinary’: listening, keeping a conversation going, saying very little sometimes, not avoiding tricky subjects and laughing together. There are always barriers to working together – mistrust, negative attitudes, language and cultural obstacles – but having a common purpose and mutually agreed expectations are key. Service users value when staff show interest in the task and share some hope and vision for the possibility of positive change. It is very important in secure services that ‘relational security’ complements the necessary physical (walls and fences) and procedural security (rules and guidelines) and staff need to take an active responsibility for their part in promoting safe and constructive working relationships.

“I shouted at my primary nurse …. and a while later he knocked on my door and said to me, what was all that about? And in the end, we laughed and I realised that maybe he trusted me after all … and that was a good feeling.” (service user in a medium secure unit)

But, what happens when things go wrong? Several authors who have focussed on ‘difficult’ exchanges and breaches of boundaries have highlighted the value of thinking about ‘windows of opportunity’ in forming working relationships (Koekkoek et al., 2010; Gutheil & Brodsky, 2008).

Defining the boundaries of interactions involves weighing up the options about how to respond in any given situation. Often people have to respond quickly, thinking on their feet. Managing boundaries well involves knowing the patient and being well-prepared. Boundaries have to be firm, yet flexible, so that they protect patients and staff and do not create further barriers that impede recovery (Lazarus, 1994). It also needs to be remembered that over-reactions or the misapplication of sanctions can be as harmful as under-reaction.

Box 6: Key ‘Do’s’ and ‘Don’t’s’ for staff wishing to achieve constructive alliances in forensic settings

DOs

- Make time to talk and listen

- Collaborate

- Be open but clear about limits; know how to ‘draw the line’

- Use common sense

- Show enthusiasm for your job/the tasks

- Communicate confidence in your patients wherever possible

- Appreciate the impact of even small decisions

- Remain sensitive to the need for confidentiality

DON’Ts

- Forget to listen/have a closed mind about what is being said

- Forget to include/ or worse, actively exclude service users

- Cross or break boundaries/rules/show favouritism

- Go along with unhelpful practices just because ‘we’ve always done this’

- Become disconnected from the reason you took the post in the first place

- Lack confidence in patients

- Think, “oh that won’t matter…”

- Over-expose patients to questions/ distress: (“go at my pace”)

Box 7: Top Tips on ‘How to get well and stay well’

- When in hospital use the support and practise skills.

- Make sure you have things to do that you enjoy and have time to relax.

- Find at least one person to laugh with and pour our heart out to.

- Try to like yourself (mostly) and others by building friendships.

- Talk to someone when things are difficult.

- Remember you have choices about what you want to do.

- Find time to do the things you like to do and can do.

- Try new and helpful things now and again.

- Recognise there are some things about life that cannot be changed, in the short term.

- Try to feel reasonably good about where you are.

- When you feel bad, you may make yourself feel better if you ask for help when you need it.

- When others feel bad or need help, you are there for them.

- Take your medication and attend therapy.

Reproduced with permission from the Ravenswood House, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, ‘A Journey of Recovery’ leaflet produced by service users.

Service user’s at Ravenswood House, a medium secure unit in Hampshire, also developed a list of ‘Top Tips’ on ‘How to get well and stay well’. These complement the staff ‘Do’s and Don’ts’ and are shown in Box 7 above.

Key area III: Risk and safety

The management of risk is, of course, fundamental to the success or failure of a forensic service aiming to support recovery. Despite acts of violence, many of the individuals in forensic mental health settings are also among the most vulnerable individuals in society (Adshead, 2000). For many, the road to recovery starts with feeling safe. This often begins with feeling in control of oneself, having relationships that are characterised by hope, trust and compassion and by having safe living conditions (Borg & Kristiansen, 2004).

When recovery begins in secure settings it needs to be recognised that the pathways by which individuals may seek control and safety may still be harmful. Jason’s story highlights real difficulties in his relationships with the people who are trying to help him. Other patients may be intimidating or violent. Managing these behaviours, and the distress that often underlies them, means that certain restrictions and professional boundaries are needed for the safety of all. But, along with the necessity for safety and security, can come a culture of control. This has the potential to lead to a risk-averse culture, defensive practice, paternalism, and overcontrol (Moore, 1995; Langan & Lindow, 2004). It is therefore crucial in recoveryoriented services to ensure that boundaries and restrictions are focused upon creating a culture of safety as a foundation for recovery. The most effective way to do this is for each organisation’s culture to be developed by staff and patients working together.

Working together to create a culture of safety means supporting people to understand how their life experiences have contributed to their risk and the impact that this has had upon their safety and the safety of others. Thus, the management of risk and safety needs to be as collaborative as any other aspect of the person’s care in recovery-oriented services (Boardman & Roberts, 2014). This collaboration should be overt and transparent, both the person and the staff supporting them feeling safe, while acknowledging the difficulties and continuing to encourage hope and growth (Barker, 2012).

In all decisions, the benefits of positive outcomes need to be balanced against the consequences of negative outcomes. “Positive risk-taking” (PRT) has been the favoured term to refer to decisions that enable patients to move forward (Morgan, 2004; Department of Health, 2007). It has been described as being, “… necessary in each aspect of mental health where the primary purpose is that of improving quality of life of service users” (Ramon, 2004). Others have noted that, “the benefits may serve as the reasons why risks are taken; the losses may refer to any possible undesirable consequences” (Robertson & Collinson, 2011). PRT gives people in Jason’s situation the opportunity to test-out and demonstrate better selfmanagement through graduated reduction in restrictions and boundaries. Constructed in an explicit and collaborative fashion, this has the potential to build trust between the person and their clinical team and has been endorsed as best practice in managing risk (Department of Health, 2007).

However, the process by which PRT is undertaken is poorly understood and underresearched. Within our workshops there was little consensus concerning PRT. Indeed, the language of ‘positive risk-taking’ was challenged as being unhelpful, inviting the perception that such activities were ‘risky’ and therefore needed to be avoided. As an alternative, one patient called this process “safety-testing” as opposed to “positive risktaking”. He described it as being, ‘like the electrical plugs in my room, you have to test any new equipment for electrical safety…. going out on unescorted leave is like that, you’re testing me to see if I can be safe, so I can prove it’. This concept of ‘safety-testing’ seems a useful way of describing a different approach to risk management where the emphasis is on helping the person pursue their chosen goals safely. We have therefore used the term ‘safety planning’ in our recent briefing examining recovery-oriented approaches to risk (Boardman & Roberts, 2014).

‘Safety planning’ is co-constructed between the person and the team they are working with; it requires a foundation of relational security (Department of Health, 2010). The service itself should acknowledge that taking a risk is a fundamental part of human growth and learning, and that the perception of a person’s offending risk must be balanced accurately against the need for them to be provided with appropriate opportunities to recover (Langan, 2008). Boardman & Roberts also argue that there is a need to make a distinction between ‘major risks’ that need to be minimised and those ‘everyday risks’ that people should be entitled to experience. In secure services this distinction is easily blurred, leading to a generally a risk-averse culture.

A recovery-oriented approach to risk assessment and management should move explicitly from external control towards the person demonstrating they can use internal mechanisms to take back control themselves. Each step along the continuum of risk-sharing should be supported by creating ‘optimal choices’ for patients within a framework of a professional duty of care. With individuals like Jason, who have the restrictions of a hospital order, the evidence for the effectiveness of such a ‘personal safety plan’ must be of sufficient standard to reassure a Mental Health Tribunal and the Ministry of Justice that the person can live safely in lower security settings or in the community.

Organisational support for ‘safety planning’ also needs to be clear, with transparent processes and appropriate guidance. The use of clear processes, which involve collaboration and discussion as the default, and do not simply rely on filling in standardised questionnaires, is likely to produce more effective risk management plans as well as plans that the person is more likely to stick to. Clear structures and support for staff in acknowledging that recovery always involves some element of risk is then necessary to facilitate the adoption of these new approaches. Far from ignoring risk, a recovery-oriented approach therefore demands that staff use all their professional skills in forming trusting relationships and understanding patients’ priorities to come to more sophisticated and better informed management plans.

Risk and ‘strengths’

Risk assessments that highlight the person’s strengths and their existing coping skills present a much more rounded picture of the person. Indeed, it has been suggested that risk assessments that fail to balance risks with strengths are inherently inaccurate (Rogers, 2000). We should therefore be careful of assessments which are couched in negative or pejorative language. A recovery-based approach which incorporates strengths-based approaches (e.g. SAPROF – Vogel et al., 2009, or START – Webster et al., 2004) are helpful in these respects. A ‘strengths-based’ approach should assist people in accessing opportunities for personal recovery and growth, while also maintaining their safety and the safety of the public.

A further example of going beyond a narrow focus on risk to developing recovery opportunities is the “Good Lives” model (see www.goodlivesmodel.com; Ward, 2002). In this approach people are encouraged to consider what they have been trying to achieve in their lives and how the process by which they have tried to achieve this has been adaptive or maladaptive. The programme assists individuals to consider how they want their lives to be different, while reflecting on the realities of their lives and building accessible support networks to cope with those realities. Its focus is positive and it incorporates elements of discovery for offenders as well as recovery, challenging them to consider what the elements of a ‘good life’ would be and how they can achieve it. The approach has been shown to have an impact on offending behaviours such as sexual offending (Willis & Ward, 2013), but has only recently been applied to offenders with mental health problems (Robertson, Barnao & Ward, 2011).

Box 8: Reflections on Jason – James Wooldridge

I’ve been asked to comment on risk as this is a huge topic regarding patients in secure hospitals. One factor in assessing risk is the level of remorse. Although I fully realise that I have been a risk to others and that is why I was in hospital, in my own personal journey I have had to consider that as a result of my offence I have received the help and support that I so badly needed. I can see that from a very bad situation there have been some positive outcomes. It has been good for me to confront the aspects of my life that were damaging my future. An aspect of this that concerns me is that some people who feel unsupported in the community commit a crime in desperation, as a ‘cry for help’. The help is then provided but when a criminal record is added to a mental health condition, the stigma that person faces is far greater and the potential for recovery suffers as a result.

One common dilemma many patients face is knowing how much (or how little) to share with their care team when experiencing distressing or frightening thoughts. Shortly before my discharge from forensic services I had thoughts about handling sharp knives that concerned me. My experience of intrusive thoughts in the past told me that this could be down to recently coming off some sedative medication that was causing some sleeplessness and giving me more time at night to think about the implications of going home. I also knew that I had never acted on disturbing thoughts in the past and I was clear on the fact that thoughts don’t necessarily lead to actions. I had a choice: tell my care team and risk my discharge being postponed or self-monitor for a few days and see if the situation improved. Fortunately, the thoughts stopped as my sleep pattern stabilised and I suppose my twenty years’ experience of living with a mental health condition provided me with the self-confidence required to see this through.

The situation above could be seen as an example of positive risk-taking and how I effectively ‘safety-tested’ myself. This involved understanding the nature of the risk, the implications and then how to monitor progress.

Key area IV: Opportunities for building a ‘life beyond illness’ – Meaningful occupation

Activities that provide meaningful occupation have a central role in promoting recovery in mental health (Strickley & Wright, 2011) – so much so that the recovery journey has been described as an occupational journey (Kelly, Lamont, & Brunero, 2010). Activities that are meaningful, interesting and fulfilling are both the means by which people recover their sense of being in the world and an outcome of recovery (Sutton, 2008). Meaningful occupation provides purpose, structure, routine and pleasure. These all contribute to a sense of personal agency. The skills and competence developed as a result of taking part in meaningful activity increase an individual’s horizons and provide opportunities to build a life beyond the secure setting. They are something to wake up for. Filling time with personally meaningful activities restores a sense of value and purpose to life promoting hope and a belief that the individual can still pursue their dreams (Hammell, 2009; Kelly et al., 2010; Mee & Sumison, 2001; Pierce, 2001; Whalley-Hammell, 2004).

If Jason is going to develop a life beyond illness that is meaningful to him he will first need to figure out what this means. An activity is meaningful when it fits with a person’s values, goals and sense of self (Lloyd et al., 2007). With his unsettled background and few achievements in life so far, Jason may not have ever considered what makes his life worth living. Previous meaningful occupations may have been anti-social, harmful, even criminal (Twinley, 2013). People like Jason are therefore faced with particular challenges in finding activities which are pro-social and health affirming (Cronin-Davis, Lang, & Molineux, 2004; Twinley, 2013).

A starting point to support someone like Jason may be to look back on what he has done before, using a strengths approach, and to identify how different activities have influenced his sense of wellbeing (Lindstedt, Söderlund, Stålenheim, & Sjödén, 2005). Also, the more that his environment can offer space for exploration and opportunities to try things out, the more he can begin to find out for himself his interests and priorities. At a basic level, ward programmes that directly involve patients in the planning and delivery of activities will empower them to help themselves (Rebeiro et al., 2001; Alred, 2003). They also contribute towards a stable, predictable structure and routine which forms the bedrock of the unit community and culture.

Staff attitudes are crucially important in this process and knowledgeable staff who take time to get to know the service user and provide the right level of support at the right time are fundamental. Jason will need to work at his own pace: fear of failure may hold him back. Staff need to be sensitive to this and ensure that activities are pitched at the right level so that individuals can always experience some success. When individuals participate in activities that are emotionally and cognitively demanding there will be a need for restorative, recuperative time. For example, in the later stages of Jason’s admission, he may be participating in challenging work around his offending behaviour, other activities may then be an important counter-balance, providing solace, refuge and a place to ‘recharge the batteries’.

Rather than simulated work programmes, forensic services are now encouraged to strive towards activities that are authentic and associated with community living (Townsend, 1997). This requires the development of interventions that tackle the systemic issues within the wider service, such as policies on access to the community, social inclusion and employment programmes which facilitate or obstruct the development of working alliances with a range of community-based settings (Cronin-Davis et al., 2004). This process can start by inviting people with a range of experiences onto the secure units including artists, teachers, musicians, animal handlers, magicians and sports experts. They bring creative ideas, energy and new perspectives and provide an opportunity to challenge stigma through integration.

Advice from our workshops included: “start small and be inclusive”; “it takes time to build relationships”; “It has taken years to build trust with colleges and community resources but the benefits have been worthwhile”.

Open employment

Most people with mental health problems want to work (Grove, Secker & Seebohm, 2005) and for people who also have forensic histories finding meaningful employment in the ‘real world’ is a key part of their recovery (Davies et al., 2007). Jason presents particular problems to employment specialists (and employers) because of his combination of mental health problems and offending history, but he should not be regarded as impossible to support into open employment. The ‘Individual Placement and Support’ (IPS) model (Becker, Drake & Concord, 1994) has been used successfully with a variety of people with severe and enduring mental health difficulties and substance misuse problems and is recommended for forensic offenders (SOFMH/NHS Scotland/Scottish Government, 2011). In mainstream mental health services IPS has been evaluated in a number of randomised controlled trials and has consistently been found to be more than twice as effective as any other approach in maintaining people with severe psychiatric difficulties in paid employment (Burns et al., 2007; Bond, Drake & Becker, 2008; Porteus & Waghorn, 2007; Rinaldi & Perkins, 2007). It is currently being tested by the Centre for Mental Health in a trial with prisoners who have mental health problems and being released into community teams (Durcan, 2014).

Although IPS is the most effective way of helping people into paid employment, as indicated above, there are a number of other possibilities in terms of voluntary roles in a variety of community settings. Open employment should not, therefore, be seen as the only – or the most superior – occupational outcome. It depends on the person and what they want to do. IPS is important because it has demonstrated that we now have an approach which can help people with offending histories and mental health problems into paid employment should they wish to do so.

Key area V: Peer support

‘Peer support’ roles are unique in terms of seeing the person’s experience of using forensic services as a positive advantage when it comes to selection and recruitment. Of course, gaining support from people who have had similar experiences has been a feature of human interaction for as long as humans have been around in groups and communicating with one another. Similarly, the importance of naturally occurring friendships between peers has long been recognised in the mental health field and peer support worker posts, voluntary and paid, have been established in both third sector and statutory mental health services. The ImROC programme believes they are particularly important in terms of supporting recovery in mental health (Repper 2013a; 2013b).

But, peer support worker posts are still rare in forensic services. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Historically, expertise has focused on what is provided by mental health workers and service users are assumed to have to be passive, rather than active, contributors to this process (Boehm et al., 2014).

- Focus groups on the possibility of establishing a mentoring system in a secure hospital, suggested competition between staff and peer workers played a role in the difficulties of establishing such roles (Boehm et al., 2014).

- In order to provide peer support based on shared experiences, the peer worker would ideally have personal experience of both mental health problems and secure services. However, many people who have used secure services do not want to remain connected to the system once they have left, or have not been encouraged to take on a new role in relation to where they received secure care.

- While current legislation is supportive of the employment of people with mental health problems, many remain excluded from the workforce. There are particular anxieties about employing people with offending histories to work alongside potentially vulnerable people in secure services.

- Additional concerns relate to the wellbeing of the peer workers themselves – it can be stressful and potentially (re) traumatising for anybody to work in secure settings.

Despite these problems, there are examples of peer workers serving a unique and valuable function in secure settings. For example, Baron (2011) describes the emergence of this new role in the US: “Forensic Peer Specialists (FPSs) are now working one-onone with referrals from mental health and drug courts to provide the otherwise unavailable ongoing support consumers may need to avoid incarceration in the future. A few FPSs work with individuals inside jails and prisons to develop re-entry plans that ensure a smooth transition to community life. Most FPSs, however, work within community-based re-entry programs to provide both personal encouragement and practical assistance in the months following release” (p. 1).

In this example, forensic peer specialists served as community guides, coaches, and advocates, working to link recently discharged people with housing, vocational and educational opportunities, and community services. Within this context, they can model useful skills and effective problem-solving strategies, as well as responding to crises. In England, Together (see www.together.org.uk) is leading a new project scoping the development of peer worker posts in secure services. Thus, there is a small, but growing, cohort of paid support worker posts in secure services.

There are also many examples of unpaid peer support. ‘Buddy’ systems and ‘listening’ projects are common in many secure settings. Patients who have been on a unit for a longer time provide support to newer patients, offering a welcome to the unit and information to familiarise them with the routines and expectations of the environment. Within secure services, these have developed from the impetus provided by the requirement for a “buddy system” as part of the implementation of ‘My Shared Pathway’ (Ayub, et al., 2013). A project called “Peer+” at Kneesworth House Hospital1 has developed these roles even further, with formalised training and dedicated on-going supervision for a team of Peer+ workers across all wards.

Patients who have completed an episode of care in a particular unit can also be invited back to support those who are earlier in their treatment pathway (e.g someone who has been through a particular therapy group might come back to help to deliver and engage subsequent group members). Similarly, people who have moved on may return to the unit to talk to existing patients about their journey. This can inspire hope and belief in the possibility of a future after discharge (Davidson et al, 1999).

Recovery Colleges

One of the most exciting new developments supporting the recovery of people using mainstream mental health services is the ‘Recovery College’ (Perkins et al, 2012). These are places where service users can deploy their knowledge and experience of mental health issues (‘experts-by-experience’) working alongside professionals to design and co-deliver ‘courses’ on topics they identify as relevant to a mixed audience of service users, professionals and family members. Courses may vary in length from a single session to a fully accredited training programme. Recovery Colleges have proved extremely popular and appear to produce range of very positive outcomes (McGregor, Repper & Brown, 2014). Most Colleges are organised on a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model, with a central ‘hub’ in the mental health service and ‘spokes’ in a variety of community settings. Some Colleges are now beginning to deliver ‘spokes’ in forensic settings (high, medium or low secure).

The role of the peer can transform what have often been very negative experiences into something positive, “I’ve been through a lot in my time, now I want to give something back, helping other people who come after me”. This gives personal satisfaction and may be a powerful element in a reparative process. It is also inclusive in that everyone has experiences to share that may be useful to others. Of course, not everyone will be interested in participating, but for those that can work in this way they can be genuinely transformative.

Box 9: James Woolridge – Reflections

I’ve reflected on what’s been written in this document so far and what lessons I’ve personally learnt from being a secure patient. I do this not only because it is healthy for me to express my feelings and thoughts on what has happened in my life but also because it could help someone else who may have walked a similar path. My well-being was helped greatly by the realisation that many of the staff wanted what I wanted – that is to move on and leave secure services. Rather than fight the system from within, which ultimately led to life being harder, it dawned on me that if I worked with the staff then I stood a much better chance of achieving my goals.

A nurse once thanked me for sharing something that they learnt from talking to me. This was very important as I realised that learning is a two-way street and I welcome the development of Recovery Colleges where everyone’s a student and the emphasis is on learning together. I truly hope that some of my fellow patients realise that there is great comfort in knowing that someone who has experienced similar, life-changing events can live a productive life even with the limitations that come with being, or having been, a secure patient.

Whilst I mentioned remorse earlier and how this has to be balanced with the fact that I received the help and support I was so desperately crying out for, I am also aware of the ‘ripple effect’ my crime of setting two fires on a hospital ward and how this impacted on my fellow patients, the nurses on the ward, my family, my work and my life in general. My wife told me that at one point during my time as an inpatient she had approached a solicitor about divorce proceedings and the thought that I could have lost everything I hold so dear is a reminder of the severity of my crime.

In a strange way my experience of secure services helped me to take responsibility for my actions and provided a long, sharp shock. It also provided me with additional experience of mental health service provision and if it hadn’t been for my crime, I wouldn’t have been asked to contribute to this document.

Quality and outcomes

The problems of measuring quality and outcomes in services to support recovery are considerable. Specifying quality indicators means that we need to know which aspects of care are reliably associated with specific positive outcomes; identifying reliable outcome indicators depends on everyone agreeing what recovery-oriented services should be striving to achieve.

In both respects, this is not easy simply because the application of recovery principles is so new that the evaluative research is lacking. Notwithstanding, it is possible to identify some quality indicators in mainstream mental health services which do receive general support and some outcome indicators that most people agree on (Shepherd et al., 2014).

In forensic services, the lack of research linking recovery practices to outcomes is even greater, but much of this paper has been devoted to try to articulate quality indicators for care at both an individual and an organisational level. These are summarised in Box 10.

Box 10: Quality indicators for recovery supporting forensic services at the level of individual and organisational care

Individual level care

- Specific attempts are made to build high quality, trusting relationships from the beginning.

- A strengths-based approach is used to underpin care planning.

- Shared decision-making is used routinely in care planning.

- Service users are provided with information about the alternative treatments available (medical, psychological, social).

- Necessary rules and restrictions (‘boundaries’) are explained clearly.

- Service users report feeling safe in the environment.

- Service users are routinely involved in planning how to pursue their chosen life goals in ways that are safe for them and others (‘safety planning’).

Organisation of care

- There is reasonable consistency of staffing.

- Service users routinely participate in co-producing policies and procedures.

- Service users routinely participate in co-designing and co-delivering the ward programme.

- Service users routinely participate in co-designing and co-delivering staff training.

- Service users are routinely involved in staff selection and appraisal.

- The unit provides access to a range of occupational activities.

- The unit has good links with a range of community agencies who can offer placements.

- The unit has access to specialist vocational staff who have received training in the ‘Individual Placement and Support’ (IPS) model.

- The unit employs appropriately trained peer support workers.

- The unit provides Befriending or ‘Listening’ schemes.

- The unit regularly uses the ‘Team Recovery Implementation Plan’ (TRIP) as a way of assessing and improving the recovery-oriented practices.

- Service users have access to ‘Recovery College’-type provision.

This list could be operationalised and used as a check-list for assessing and developing the service. This would be best achieved through a process of co-production.

In relation to outcomes, there is greater commonality for people in forensic services and those in mainstream mental health services. We would therefore argue that the same list of outcome measures as ImROC proposed for mainstream services could be used here, perhaps with minor modifications. These are shown in Box 11.

Box 11: Summary recommendations for recovery outcomes measures (based on Shepherd et al., 2014, Supporting Recovery in Mental Health – Quality and Outcomes, Centre for Mental Health, London).

Definite

DOMAIN 1 – Quality of recovery-supporting care – To what extent do service users feel that staff in services are trying to help them in their recovery? Recommended measure: INSPIRE.

DOMAIN 2 – Achievement of individual recovery goals – To what extent have goals, as defined by the individual, been attained over time? Recommended measures: Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), narrative accounts.

DOMAIN 3 – Subjective measures of personal recovery – To what extent do individuals feel that their hopes, sense of control and opportunities for building a life beyond illness have improved as a result of their contact with services? Recommended measure: Questionnaire on the Process of Recovery (QPR).

DOMAIN 4 – Achievement of socially valued goals – Has the person’s status on indicators of social roles improved as a result of their contact with services? Recommended measures: Relevant items from Adult Social Care Outcomes Framework (2012), Social inclusion web.

Possible

DOMAIN 5 – Quality of life and well-being – Has the person’s quality of life and/or well-being improved? Recommended measures: MANSA, WEMWBS.

DOMAIN 6 – Service use – As a result of their recovery being supported, has the person made an appropriate reduction in their use of other mental health services? Recommended measures: Relevant items from Mental Health Minimum Data Set & NHS Outcomes framework (but beware!).

Conclusions

We began with asking a simple question of our workshop participants: “What helps and what hinders recovery?” What emerged from those conversations was that recovery for forensic service users is, in many respects, identical to recovery for mental health service users in non-forensic settings. But, the recovery journey of people in forensic services is significantly different from others in one crucial aspect: people with offending histories have to address in some way the reality of what they have done and what brought them to forensic services. For forensic service users, personal recovery therefore needs to include offender recovery. This means addressing guilt, shame, confusion, turmoil – sometimes denial – with sensitivity and respect. If this can be done in such a way that the person is helped to ‘come to terms with themselves’ then personally defined recovery becomes genuinely possible.

Support for personally defined recovery should therefore be incorporated into mental health and well-being interventions for people in forensic services, just as for those outside of them. Risks need to be identified and managed so that the person can pursue their hopes and dreams safely. High quality relationships of trust and collaboration need to be built between service users and staff and service users should be able to participate as fully as possible in all aspects of their care through informed choices and shared decision-making. Care planning needs to be founded on the person’s strengths, while acknowledging their difficulties. Organisations then need to commit to developing a culture of safety for service users and staff and provide support for staff in maintaining their support for recovery. Trusts, directorates and leadership teams need to consider how they can invest in transforming the culture and practices in their services to prioritise recovery. Finally, contact with the wider community – peers, family, friends and informal social networks – needs to be actively encouraged – it provides the strongest foundation for hope and a positive sense of identity into the future.

Box 12: Final reflections – James Wooldridge

Thinking about Jason and recovery in this document has been challenging for me in many ways. I first heard about recovery as a way of living whilst a patient in secure services and I truly believe – then and now – that those who work in secure services have a far greater opportunity to work to support recovery than staff in acute ward settings. This is because in the acute settings I’ve experienced staff levels are lower, staff/patient interactions are limited and the emphasis seemed to be on throughput rather than high quality care.

In discussing these issues I tried to include many of the dilemmas that I personally faced whilst a patient, such as disclosure, remorse, having bad days, as well as the frustrations of being in such a closely-monitored environment. Above all, I wanted to convey a sense of hope. This is the cornerstone of recovery and needs to be nurtured by both staff and patient alike. In my recovery I would particularly acknowledge the role that my wife, my work, my music and my dog have played in maintaining my hope and supporting my recovery. Thanks to them and to all of you for reading this.

References

Adshead, G, (2000) Care or custody? Ethical dilemmas in forensic psychiatry. Journal of Medical Ethics 26, 302–304

Adshead, G. (2010) Introduction to ethics. In: A. Barlett & G. McGauley (Eds), Forensic Mental Health: Concepts, systems, and practice (pp. 293-294). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Adshead, G. (2012a). Their Dark Materials: Narratives and Recovery in Forensic Practice. (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Their%20 Dark%20Materials.%20narratives%20and%20 recovery%20in%20Forensic%20Practice%20 Gwen%20Adshead.x.pdf. Accessed on 24 June 2013)

Adshead, G. (2012b) This thing of darkness: Index offence work and recovery. Paper presented at the 5th Forensic Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (ImROC) Seminar “Promoting recovery through positive working alliances”, The Learning Centre, South Staffordshire & Shropshire Healthcare Foundation Trust, 11 October 2012.

Aiyegbusi, A. & Clarke-Moore, J. (2008) Therapeutic Relationships with Offenders: An Introduction to the Psychodynamics of Forensic Mental Health Nursing

Aiyegbusi, A. & Kelly, G. (2012) Professional and Therapeutic Boundaries in Forensic Mental Health Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Allen. S. (2010) Our Stories: Moving On, Recovery and Well-being. South West London & St. George’s Mental Health Trust Forensic Services.

Alred, D. (2003) Programme Planning. In: L. Couldrick & D. Alred (Eds.), Forensic Occupational Therapy. London: Whurr.

Ayub, R., Callahan, I., Haque, Q. & McCann, G. (2013) Increasing patient involvement in care pathways. Health Services Journal, 3 June 2013. (http://www.hsj.co.uk/ home/commissioning/increasing-patientinvolvement-in-care-pathways/5058959.article)

Barker, R. (2012) Risk and Recovery: Accepting the complexity. In: G. Drennan & D. Alred (Eds), Secure Recovery: Approaches to Recovery in Forensic Mental Health Setting (pp. 23-40). London: Routledge.

Baron, R. (2011) Forensic Peer Specialists: An Emerging Workforce. Center for Behavioral Health Services & Criminal Justice Research, Policy Brief, June 2011.

Bartlett, A. and McGauley, G. (2010) Forensic Mental Health: Concepts, systems, and practice. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Becker, D.R., Drake, R.E. & Concord, N.H. (1994) Individual placement and support: a community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Mental Health Journal, 30, 193-206.

Boardman, J & Roberts, G. (2014) Risk, Safety and Recovery, ImROC Briefing Paper 9. London: Centre for Mental Health and Mental Health Network, NHS Confederation.

Boehm, B., Tapp, J., Carthy, J., Noak, J., Glorney, E. & Moore, E. (2014) Patient Focus Group Responses to Peer Mentoring in a High Security Hospital. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 13: 1–10.

Bond, G. R., Drake, R.E. & Becker, D. (2008) An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31, 280-290.

Borg, M., & Kristiansen, K. (2004) Recoveryoriented professionals: Helping relationships in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, October 2004; 13(5): 493 – 505

Bowser, A. (2012) Nothing for us without us either. In : G. Drennan & D. Alred (Eds), Secure Recovery: Approaches to Recovery in Forensic Mental Health Settings (pp. 41-54). London: Routledge.

Burns, T., Catty, J., Becker, T., Drake, R., Fioritti, A., Knapp, M., Lauber, C., Tomov, T., Busschbach, J., White, S. & Wiersma, D. (2007) The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: a randomised controlled trial, The Lancet, 370, 1146-1152.

Copeland, M. (2011). The Wellness and Recovery Action Plan. Peach Press: West Dummerston, VT.

Cronin-Davis, J., Lang, A., & Molineux, M. (2004) Occupational Science: The forensic challenge. In Molineux (Ed.), Occupational Science for Occupational Therapists. Oxford: Blackwell.

Davidson, L., Chinman, M., Kloos, B., Weingarten, R., Stayner, D., & Tebes, J.K. (1999) Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6 (2), 165-187.

Davies, S., Clarke, M., Hollin, C. & Duggan, C. (2007) Long-term outcomes after discharge from medium secure care: a cause for concern, British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 70-74.

Davies, S., Wakely, E., Morgan, S. & Carson, J. (2012) Mental Health Recovery Heroes Past and Present. Pavilion Press: Sussex.

Department of Health Secure Services Policy Team. (2010) See, think, act: Your guide to relational security. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health. (2007) Best Practice in Managing Risk: Principles and evidence for best practice in the assessment and management of risk to self and others in mental health services. London: Department of Health.

Dorkins, E. & Adshead, G. (2011) Working with offenders: challenges to the recovery agenda. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 17, 178-187.

Dowling, H., & Hutchinson, A. (2008) Occupational therapy – it’s contribution to social inclusion and recovery. A Life in the Day, 12(3), 11-14.

Drennan, G., & Alred, D. (2012). Secure Recovery: Approaches to Recovery in Forensic Mental Health Settings. London: Routledge.

Durcan, G. (2014). Employment for offenders. Available at http://www.centreformentalhealth. org.uk/employment/andoffenders.aspx. (Accessed 30th Jul 2014).

Eunson, H., Sambrook, S., & Carpenter, D. (2012)Embedding recovery into training for mental health practitioners. In: G. Drennan & D. Alred (Eds), Secure Recovery: Approaches to Recovery in Forensic Mental Health Settings (pp. 172-185). London: Routledge.

Ferrito, M., Vetere, A., Adshead, G., & Moore, E. (2012) Life after homicide: accounts of recovery and redemption of offender patients in a high security hospital – a qualitative study. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 23(3), 327-344.

Francis, R. (2013) Implementing the recommendations to The Francis Inquiry: A Year On. http://www.healthcareconferencesuk.co.uk/francis-inquiry-a-year-on.

Grove, B., Secker, J. & Seebohm, P. (2005) New Thinking about Mental Health and Employment. Oxford: Radcliffe

Gutheil, T.G. & Brodsky, A. (2008) Preventing Boundary Violations in Clinical Practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Hammell, K. (2009) Self care, productivity and leisure, or diimensions of occupational experience? Rethinking occupational “categories” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76, 107-114.

Hillbrand, M. & Young , J. L. (2008) ‘Instilling hope into forensic treatment: The antidote to despair and desperation’. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 36, 90 – 94.

Kelly, M., Lamont, S., & Brunero, S. (2010) An occupational perspective of the recovery journey in mental health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(3), 129-135.

Koekkoek, B., van Meijel, B., van Ommen, J., Pennings, R., Kaasenbrood, A., Hutschemaekers, G & Schene, A. (2010) Ambivalent connections: a qualitative study of the care experiences of non-psychotic chronic patients who are perceived as ‘difficult’ by professionals. BMC Psychiatry, 10: 96 http:// www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/10/96

Langan, J. (2008) Involving mental health service users considered to pose a risk to other people in risk assessment. Journal of Mental Health, 17(5), 471 – 481

Langan, J., & Lindow, V. (2004) Living with Risk: Mental Health Service User Involvement in Risk Assessment and Management, Bristol: Joseph Rowntree Foundation/The Policy Press.