Across UK mental health services, most NHS Trusts and voluntary sector services are actively recruiting people with personal experience of mental health challenges to newly created ‘Peer Support Worker’ positions. A national competency framework for peer workers has been agreed (Health Education England, 2020) and accompanying training programmes have been established (see for example, Bradstreet, 2006; Repper et al, 2013 a & b). The value that such employees can bring has been widely documented (see, for example, Repper et al 2013a, Davidson et al, 2012; Watson and Meddings, 2019). The benefits for people supported by peer workers can include increased self-esteem, confidence, problem-solving skills, hope, positive feelings about the future and a sense of empowerment. Peer workers have also been found to bring benefits to the teams and services in which they work by providing inspiration, challenging negative attitudes and facilitating a better understanding of the challenges people using the service face. There are also benefits for the Peer Support Workers themselves including increased confidence and self-esteem, a positive sense of identity and value, feeling less stigmatised and empowered in their own recovery journey.

20. The Value and Use of Personal Experience in Mental Health Practice

Rachel Perkins and Julie Repper

The advent of Peer Support Workers who explicitly draw on and share their personal experience of mental health challenges in their work has highlighted two key issues.

1. Peer Support Workers are not the only employees with experience of mental health challenges.

There are many nurses, doctors, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers and other mental health professionals who have themselves experienced mental health challenges. Indeed, workforce surveys of staff in three mental health Trusts have revealed that up to 62% of staff have experience of mental health challenges and/or of caring for someone in the family with mental health conditions (Morgan and Lawson, 2015). Are these people also ‘Peer Workers’?

We would argue that, while their personal experience of mental health challenges can undoubtedly enhance the work of trained mental health professionals, they are primarily employed for their expertise in their chosen profession and in this professional role, their primary source of reference is their professional knowledge. Peer support workers bring a different kind of expertise: experiential knowledge drawn from their personal experience of recovery with mental health challenges. They also offer a different kind of relationship: one based on mutuality (by definition, as peers they share experiences), reciprocity (learning together rather than one being the expert and the other being recipient of that expertise) and cocreation (with the person they are supporting) of understandings, ideas and ways forward. Peer workers are not employed to deliver in any type of intervention or therapies; they work outside traditional power hierarchies and claims to special, professional, knowledge.

This peer to peer relationship is quite different to the relationship between a mental health professional who also has personal experience of mental health challenges: Such a professional is very much part of traditional hierarchies and has claims to the special knowledge of their professional training. This does not mean that professionals should not use their personal experience of mental health challenges in their work, rather that these do not make them a ‘Peer Worker’. Indeed, if we only employ people with personal experience of mental health challenges in designated ‘peer’ roles, we risk reinforcing the destructive ‘them’ and ‘us’ barriers that remain within mental health services.

Breaking down barriers, reducing ‘othering’, improving staff expectations of people using services and challenging stigma and discrimination more generally, can only be achieved if personal experience of mental health challenges among all mental health professionals is valued at organisational, team and interpersonal levels. Peer Support Worker roles are important, but it is also critical that people with personal experience of mental health challenges can a) access training for all of the roles within mental health services, b) are explicitly welcomed to apply for these roles in organisations, c) are supported to use these experiences appropriately, effectively and safely in their practice, d) receive the employment support that they require to work to their full potential.

2. Lived experience of mental health challenges is not the only sort of personal experience that may be relevant and useful in work within mental health services.

People working in mental health services may bring personal experience of many life challenges in common with the adversities faced by people using services: bereavement, physical health challenges and impairments (themselves or in someone close to them), relationship difficulties, loneliness, redundancy, being a refugee, racism, sexism, heterosexism and other types of discrimination and disadvantage. We know that mental health challenges do not occur in a vacuum, they occur in the context of a family, a relationship, a community, a culture and a place … All of these are important in understanding the meaning of mental health challenges for someone using services and the possibilities and opportunities that are available to them. Again, mental health workers may have personal experiences in common with the person/people who they support. These experiences may be a cause or consequence of mental health challenges, or they may seem to be unrelated. It is the fact that professionals working in services and people using services have experiences in common that is key to building different kinds of relationships that draw on shared human experience and insights rather than relying purely on particular professional skills and strictly professional roles, that is the key here.

Recovery is about rebuilding a life – discovering and pursuing the things you value, your interests and possibilities. The experience that staff have of different activities, interests and possibilities may be equally important in assisting people in rebuilding their lives as their professional skills. We need to extend our vision of ‘lived experience’ beyond that of mental health challenges to encompass the full range of personal experience that may be valuable and useful in mental health work. Every professional brings to their work, not only their professional expertise, but also their:

- Personal life experiences.

- Interests, hobbies, skills, likes, dislikes and activities outside work.

- Culture, community knowledge and contacts.

- Past struggles, difficulties and disappointments in life. Some may also bring their experience of the mental health challenges of their relatives friends and people who are close to them, and, of course, their own experience of mental distress.

Why share personal experience?

“Contrary to previous research on patients’ experiences, the themes that predominated related to the emotional not physical environment in which they stayed … relationships form the core of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission …” (Gilburt, et al, 2008)

Relationships are central to the experience of mental health services and central to recovery. Many people with mental health challenges feel cut off from families, friends and communities.

“Social relationships and social integration are as (if not more) important as smoking, drinking, exercise and obesity in determining health and wellbeing.” (Holt-Lunstad et al 2010)

One of the key aims of services must be to assist people to rekindle those ordinary relationships on which all of us rely. However, relationships with mental health professionals can be particularly powerful … for good or ill. If the mental health professionals who provide your treatment and support do not seem to respect you, trust you, believe what you say, believe in your possibilities, how can you hold on to hope and believe in yourself and your own possibilities? We know that trusting, empowering and hope-inspiring relationships are central to recovery and recovery-focussed services:

“Meaningful relationships, peers, and role models increased participants’ motivation to change especially when shared experiences facilitate identification with these significant others” (Price-Robertson et al, 2016)

Yet in relationships between mental health professionals and the people they support there are many barriers:

• One person talks about their thoughts and feelings, the other does not

• One is in the role of helper and the other is in the role of being helped

• One is there because they need help (or someone else thinks they need help) the other is paid to be there • Differences of culture, ethnicity, age, gender, class, faith …

• One person is ‘the expert’ who defines what is wrong and prescribes what they should do (and, at the bottom line, can force them to accept their views) … and if the person using services does not agree with the ‘expert’ then they may be defined as ‘lacking insight’ or ‘non compliant’ and their perspective discounted.

These are all barriers that divide ‘them’ from ‘us’ and they are maintained by, often unwritten, traditional rules that govern relationships within mental health services: the ‘expert’ knows best, and ‘experts’ must give nothing of themselves, maintain ‘professional boundaries’. It may be beyond the power of any individual professional to dismantle traditional heirarchies and power relationships. However, if we are really to respect and promote the recovery of people using services then we must reach across that divide between ‘them’ (the people using ‘our’ services) and ‘us’ (those of us who are employed to ‘fix’ them); erode the barriers that exist within services – and the communities they provide for. First we must recognise the expertise of lived experience as well as professional expertise and bring these together in a process of ‘co-production’ (see Lewis et al, 2017) where equal value is placed on experiential knowledge as upon specialist professional knowledge. Second, we must foster relationships that recognise and demonstrate our shared humanity. As Wyder et al (2013) found “those who felt they were treated as somebody who could be counted on, as a fellow human being … felt respected and the experience allowed them to gain self-confidence.”

Barriers and risks

In some services there exist physical barriers between people using services and those working in them (separate cups, separate toilets, signs declaring that staff do not tolerate aggression or violence) but boundaries also exist in relationships between professionals and people using services – and in how we have defined what ‘being professional’ means. Too often this includes the routinisation of ‘non-disclosure’. The sharing of personal experience by mental health professionals has often been perceived as violating professional boundaries and codes of conduct (Lovell et al, 2020; Dunlop et al, 2021). Organisational cultures typically discourage ‘disclosure’ on the part of professionals and professionals feel that doing so might result in disciplinary action (Lovell et al, 2020; Dunlop et al, 2021). Whilst such beliefs may be widespread, as Lovell et all (2020) and Dunlop et al (2021) point out, across the main codes of practice, standards and ethics for professionals, the sharing of personal experience is not forbidden. Indeed, there is much to be lost if mental health practitioners do not use and share their personal experience in their work

“self-disclosure can help foster a trusting relationship between service user and practitioner through similarity, credibility and shared understanding.” (Dunlop et al, 2021)

Traditionally, the sharing of personal experience has been referred to as ‘disclosure’ or ‘selfdisclosure’. We prefer not to use this term because it has negative connotations of ‘disclosing some shameful secret’. We prefer the term ‘sharing personal experience’ to indicate the positive value of such experience. Just as there are risks associated with the inappropriate use of professional expertise (e.g. based on our professional judgements we might encourage people to ‘be realistic’ about their limitations, thereby eroding their hope and life chances – ‘You will never be able to cope with the stress of a job’) there are also risks associated with the inappropriate use of personal experience. The sharing of personal experience may be considered inappropriate if, for example, it:

• Removes the focus from the person being supported to the person employed to provide support.

• Burdens the person being supported with too much information leaving them worrying about the professional and the difficulties they are facing.

• Makes the person reluctant to ask for help because the professional already has so many problems of their own with which to deal.

• Creates a competitive situation between the professional and the person about whose challenges are greatest (e.g. ‘Don’t worry about taking that medication – I have taken far more than that for years.”)

• Creates confusion about the nature of the relationship (moving beyond a work relationship to friendship or even intimacy).

• Becomes prescriptive if the professional implies that the way they dealt with difficulties is the ‘correct’ or only way (‘ I know what you mean, you should do what I did …’).

• Invokes envy in the person being supported (if they see the professional coping far better with similar problems than they are).

• Creates difficulties for the mental health practitioner when they share experiences they are not ready to share or opens up subjects they are not comfortable discussing leaving them feeling exposed and vulnerable.

• Provides personal details that might cause confusion about the nature of our relationship or potentially put us or our family members at risk, for example our home address or details of the school our children attend. (see, for example, Henretty and Levitt, 2010; Audet and Everall, 2010; Ruddle and Dilks, 2015; Dunlop et al, 2021).

The value of sharing personal experience with people using the service

In many walks of life, sharing personal experience is an important feature of trusting and respectful relationships. Within mental health services, sharing personal experience helps us to reach across the ‘them’ and ‘us’ divide and foster those human to human relationships that can be critical in helping the person to feel valued and more than ‘just a patient’. Trust is a twoway street: if mental health professionals expect people using services to trust them with the intimate details of their lives, they must give something of themselves as well. It is noteworthy that the one of the core interventions developed by the widespread ‘Safe Wards’ initiative (which resulted in 15% decrease in the rate of conflict and a 24% decrease in the rate of containment) was the ‘know each other’ exercise1 . This involved staff providing some information about themselves to residents on the ward – their likes, dislikes, hobbies, interests, favourite TV programme, film, book, music etc. – and encouraging people using the service to provide similar information, thus fostering interactions based on shared humanity and similarity – beyond their previously fixed identities as ‘nurse’ and ‘patient’.

The sharing of personal experience can: • Foster authentic, human to human interaction. • Promote an alliance and build trust. • Normalise experience: enabling people to feel less alone and that much of what they are experiencing (like hopelessness, despair and anger) are common reactions to what has happened (see Deegan, 1988). • Build self-esteem. • Challenge myths and misconceptions. • Facilitate self-exploration and encourage people to talk more openly about their challenges. • Show similarities that can provide reassurance and alternative ways of understanding experiences and approaching challenges. (See, for example, Henretty and Levitt, 2010; Audet and Everall, 2010; Dorset Mental Health Forum, 2013; Morgan and Lawson, 2015; Ruddle and Dilks, 2015; Meddings, Morgan and Roberts, 2019; Lovell et al, 2020; Dunlop et al 2021).

The value of sharing personal experience within the team or service

The sharing of personal experience can also be a valuable resource for the team/service in which staff work. The benefits include:

• Providing access to a greater range of talents that may be of use to people using the teams’ services. This might include, for example, language competencies, music and sport. The interests and skills of staff can be used to provide pointers to helping clients to access different activities and community opportunities.

• Providing the team with greater range of expertise. This might include the experience of different kinds of challenges and knowledge of different cultures and communities. For example, an understanding of how mental health challenges are construed in different cultures and communities can provide insight into the experience of people using the service: the challenges and possibilities facing people from different cultures and communities and greater understanding of their feelings and behaviour.

• Making the team a more supportive place to work. If team members feel that they can talk about the challenges they are facing then this can help colleagues to feel more supported and enhance staff well-being.

“Within the team I have referenced some of my difficulties. It is an open environment from that point of view … I do think that one being open can bring more openness in others. It almost gives ‘permission’ for people to feel they have the opportunity to be open about difficulties they face.” (cited in Perkins, 2021)

• Contributing to the breaking down barriers and reducing ‘othering’. If everyone feels able to talk about the challenges they are facing then this can lead to a recognition that “…everyone has their own experience of recovery as a consequence of the wideranging vicissitudes of life that leave noone unscathed.” (Perkins, 2021)

If staff are encouraged to see their personal experiences as assets and resources in their practice, and the whole team values the range of different experiences that members bring, then it is far more likely that staff will be more open about themselves. What they previously felt compelled to hide – as vulnerabilities or weaknesses – can more confidently be shared. In a staff survey undertaken in Devon Partnership Trust, 43% of respondents identified as having lived experience of mental health problems, but one third of respondents with lived experience felt unable to be open with their managers and colleagues. The most frequent reason for not disclosing their mental health problems was fear of stigma, misunderstanding and rejection (cited in Morgan and Lawson, 2015). If people feel unable to share these experiences, they are also unable to discuss the sort of supports and adjustments that might enable them to stay well and work to their full potential.

There can be no absolute rules about using personal experience at work – we cannot replace the traditional ‘tell nothing of yourself’ with ‘tell everything’. Ultimately, we must be guided by the purpose of our relationship with people using services: to help them in their journey of recovery. Individuals and situations differ so all professionals need to make informed judgements about what we can usefully share, why, when, with whom, how and how much. It is noteworthy that Henretty and Levitt (2010) found that 90% of mental health professionals had shared personal experiences with people using services, yet this is rarely explored in supervision and clinical discussions, there are few guidelines about such matters about and professional guidelines have typically been silent on such issues. As Ruddle and Dilks (2015) say, “Everyone is doing it but no-one is talking about it. It is time we started.”

Starting to talk about sharing personal experience

The ‘Competence Framework for Mental Health Peer Support Workers’ (Health Education England, 2020) states that a core role of Peer Support Workers is to draw on and share their lived experience of mental health challenges and other life experiences in a way that is relevant to the person and their circumstances, helps them to know that they are not alone, empowers them and gives them hope and helps them to discover the recovery and self-care practices that work for them while maintaining appropriate boundaries. The training of Peer Support Workers explicitly addresses how they might do this and considers the risks as well as the benefits of sharing personal experience. However, the training of other mental health practitioners does not give such detailed consideration about using their personal experience to enhance their professional roles. Some guidelines have begun to emerge for those mental health professionals who have personal experience of mental health challenges that they are willing to share. For example, Meddings, Morgan and Roberts (2019) suggest that mental health professionals think about what facets of their personal experience of mental health challenges they are comfortable about sharing, when to share it and why – the reasons for sharing – and how to share it. They recommend that practitioners think about two key dimensions ‘Does it benefit the person you are sharing with?’ and ‘Is it okay with you?’. Scior (2017) developed ‘Honest, Open and Proud for Mental Health Professionals’ – a self-help intervention that supports mental health professionals with lived experience of mental health challenges to make decisions about ‘disclosure’. This helps practitioners to consider the pros and cons of sharing, contexts and levels of sharing and how to share their experiences in a meaningful and safe way.

More recently, guidelines for the sharing broader aspects of personal experience have begun to emerge. For example, Dorset Healthcare University NHS Foundation Trust (Morgan and Lawson, 2015) have developed guidelines for staff sharing their lived experience that moves beyond personal experience of mental health challenges to personal experience of overcoming health challenges and challenging life circumstances. This makes it clear that personal experience of challenges and adversity is an asset in mental health practice, and provides guidance to all mental health practitioners. The guidance takes the form of a set of principles that staff should consider and describes the benefits of sharing as being: to inspire hope, improve partnerships with people who use services and their families, reduce stigma and promote staff well-being by creating a culture of openness within teams. Based on work by Dunlop et al (2021), Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust have developed a ‘Sharing Lived Experience Framework’. This takes a yet broader perspective on the sharing of personal experiences to include such things as hobbies, interests, sexuality, religion and culture. The Framework spans what it describes as ‘the disclosure process’

“… from pre-disclosure planning and reflection, to in-the-moment questions to consider internally and dialogically with the service user, and finally to post-disclosure reflection. Such reflection should consider the impact of disclosure on the service user, the practitioner and the relationship, and how the experience should inform future disclosure decisions.” (Dunlop et al, 2021)

The framework takes the form of a series of questions for guided self-reflection, clinical supervision and training. It also explicitly includes questions relating to the professionals ‘motivation for sharing’: ‘healthy motivations’ (such as normalising/ demystifying, offering hope and/or ideas for coping, being seen as human and strengthening the relationship) and ‘warning signs’ when “the motivation for disclosure is unhealthy”. This guidance focuses on sharing personal experience with individuals using the service – it does not consider the benefits of sharing personal information within the team/service. Building on the work of Morgan and Lawson (2015) and Dunlop et al (2021), an IPS Grow working group developed guidelines on using personal experience within ‘Individual Placement and Support’ evidence based supported employment programmes (Perkins, 2021). This included the value of sharing the full range of personal experience both in individual work and within teams and services.

The purpose of this ImROC briefing paper is to build on all of this existing work. It considers the use of all relevant personal experience and how this might appropriately and safely be used in individual work, and in increasing the expertise available to the team, to promote the recovery of people using services. We also explore how organisations might create a culture that both values the personal experience of all its employees and encourages them to use it in their work.

Guidelines for professionals in sharing personal experience

Following Dunlop et al (2021) and Perkins (2021), this might include 3 elements:

• Preparation: what life experience you bring that may be useful and what you feel able to share and with whom

• Making decisions in individual or team interactions: how, how much, what, why, when and with whom (a colleague, the team, a person you are supporting).

• Reflecting on the use of personal experience: lessons learned – what was effective, what was less useful

Preparation

Every practitioner needs to think, in advance, about what personal experience we feel able to share with people using the service, with their manager, with colleagues and other team members. This is important because:

• When we have shared something with someone we cannot ‘unsay’ it.

• Once you have shared an experience with one person, we need to be prepared for them to share this with others. We cannot ask or expect anyone to keep it to themselves, this creates confusion about the nature of our relationship.

• We need to be able to explain the reasons why we have shared any aspect of our personal experience if asked.

• We need to consider the possibility that sharing one aspect of our experience might lead to further questions, we must prepare ourselves by thinking about how we might answer these or how we can close these down in a supportive manner.

• Our mood and day to day stresses can influence our responses, if we prepare in advance we are more likely to respond in a mindful manner.

We may be prepared to share different things with different people and for different purposes. For example, if we are having difficulties at home we may share these with our supervisor or manager in order to gain support or adjustments in our work. This may well be something that is far too raw to share with colleagues or people we support and is very different from sharing personal experiences to help people we support or colleagues in their work.

It is reasonable to expect all mental health practitioners to bring something of their experience of life to benefit colleagues and people they are supporting but each of us needs to make decisions first, about what we feel able to share and second about how we present it. This will influence the way in which it is heard and the impact it has on ourselves and the people we share it with. For example, many people will have experienced the breakdown of a relationship, and this may be useful in understanding the experience of people we are supporting colleagues who face similar challenges and supporting them. However, we need to think about how much detail we present and how we frame it. Without prior planning and consideration, it is too easy to find ourselves sharing all the ‘gory details’. This risks leaving us feeling very exposed and embarrassed and burdening others with an excess of information. While we may need to acknowledge the gravity of what happened for us, if we present our experience without any information about how we tried to cope and move forward then we risk making others feel hopeless and negatively influence the way in which they perceive us: we are ‘vulnerable’, unable to cope, untrustworthy.

See Table 1 for questions that you might want to reflect on in deciding in advance what personal experience you may use in your work.

Table 1. Preparation: Some questions for reflection

• What personal experiences have I got that might be helpful in my work? For example: life history and family background; hobbies, skills, interests; culture; faith and spirituality; difficulties we have experienced in the past.

• Which of these am I comfortable about sharing: with colleagues to inform their work? with people I support to help them in their recovery? (n.b. if you share this with one person others are likely to find out. Are you comfortable for this information to be available more widely?)

• How might sharing this information be helpful to: colleagues to inform their work? people I support to help them in their recovery? (n.b. think about how you might explain sharing this information to a sceptical colleague or manager)

• How am I going to present this experience and how much detail am I willing to share: with colleagues to inform their work? with people I support to help them in their recovery? (n.b. how you present it will influence the impact it has on you and the people we share it with)

• What experiences and which details am I NOT prepared to share?

• What information do I put on social media? (n.b. this public information and potentially available to colleagues and people we are supporting)

Making decisions in individual interactions

In everyday life, when we meet people we show an interest in them, and give something of ourselves. This may be something as basic as saying ‘I love the colour of your jumper – green is my favourite colour’. Such interactions help develop our relationship with the person and are equally important in forming relationships with people we support or our colleagues: developing a rapport with the person, showing an interest in them, going beyond the strict requirements of gaining/giving information that enables us to fulfil our professional role. Indeed, the personto-person interaction that we have is an important foundation of the mutual trust that will be critical to the effectiveness of any professional intervention. Sharing personal information or experiences sets the groundwork for the relationship that we will have with colleagues or people we support. What it is useful to share, when and how has to be considered in the context of every individual interaction.

There will be individual differences. While there may be some colleagues and people we support who value practitioners sharing something of themselves and their experiences, others will prefer to keep this to a minimum. We need to be sensitive to this and it is probably sensible to start small, and in relatively non-threatening areas (e.g. ‘Were you OK getting here in the dark – I hate these short winter days) and see how the person responds.

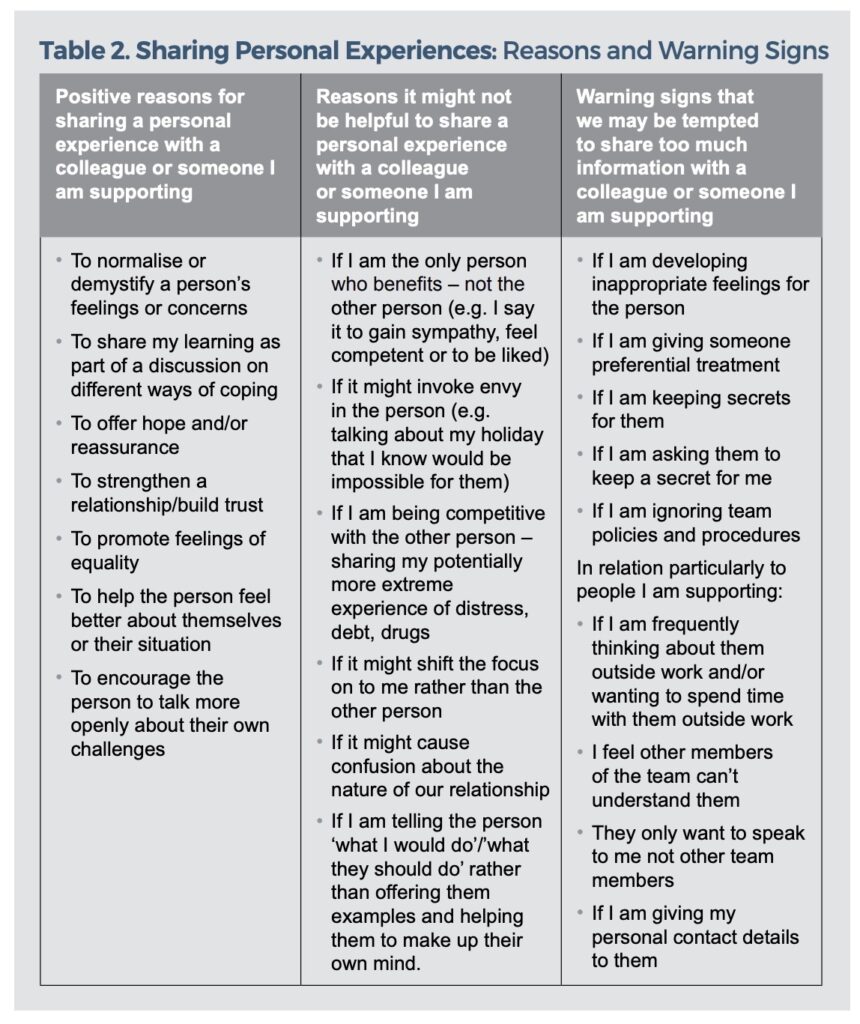

Moving beyond relationship building, we need to give more attention to the experiences we share to support people with specific aspects of their own recovery. We need to think about what we select to share, how much detail will be helpful, and why we are sharing this experience: the possible benefits and risks attached, and warning signs that we may be tempted to share too much (see Table 2).

We also need to think about getting the timing right in terms of my relationship with the person, are they in the right place to hear this today, do I feel comfortable discussing it right now, is there space and time to cope with any possible conversation that might ensue – will we have to leave issues hanging?

Finally, it is generally wise to avoid saying ‘I know what you mean’. No two experiences are the same – individuals and circumstances differ. No-one can ever fully understand the impact of an event on another person. It is usually preferable to use a form of words like ‘I don’t know what it was like for you, but when X happened to me I felt ….”. Nor should we assume that our way of dealing with things is the only way or the right way, merely one in a range of options: ‘I did X but I know of other people who found Y or Z helpful.’

Reflections after sharing personal experience

Just as it is wise to reflect on professional judgements and interventions, it is important to reflect on our experience of sharing of personal experience. Whether such experience has been shared with colleagues or someone we support, reflection allows us to learn from or experience and can inform future decisions about sharing. Table 3 provides some questions that might assist such reflection. While personal reflection may be important, it can also be useful to use supervision or discussions with colleagues for this purpose.

Table 3. Learning from our experience of sharing: some questions for reflection

• How did my experience of sharing personal experience go – what impact did it have on The person with whom I shared? Our relationship? Me?

• How did it help someone I support in their recovery or a colleague in their work? What worked? What didn’t work? Why?

• How did sharing my personal experience feel at the time and how do I feel now?

• What did I learn from my experience of sharing?

• Do I want to, and would it be useful for me to, share my learning with the team?

Creating a culture in which personal experience is valued and used

If mental health practitioners are to bring both their professional expertise and their personal experience to their work then we need to create a culture – values, beliefs and behaviours – that explicitly and implicitly respects both of these. Leadership is critical in creating a culture where personal experience is valued and used alongside professional expertise. Leaders, at all levels of the organisation, need to commit to making this happen.

Directors, managers and team leaders all need to:

• Ensure that personal experience of all staff is explicitly valued in all documentation, policies, procedures and operational policies.

• Personally model the appropriate sharing of personal experience. This implicitly ‘gives permission’ for other members of staff to do likewise.

• Create expectations that every member of staff will use some of their personal experience in their work. This might usefully include a requirement that all staff prepare a brief biography of themselves which includes their professional experience, something about their interests and activities outside work and their reasons for working in this area. Together with photographs, these might then be shared on ‘meet the directors and managers’ pages of a web-site and a ‘meet the team’ information leaflets and noticeboards.

• Explicitly values personal experience within the recruitment process.

– Job descriptions and person specifications should indicate that personal experience of life challenges, including mental health conditions, is a desirable asset and that it is essential that the post-holder is willing to use some relevant personal experience in their role (e.g. life experience, interests and activities outside work, cultural and community knowledge, as well as difficulties and disappointments in life).

– Information provided to potential applications indicates that personal experience is valued alongside professional expertise and experience.

• Clinical/Practice Supervision models, values, explores and develops use of personal experience in practice.

– The supervisory relationship should be one in which both supervisor and supervisee share personal experience and foster mutual learning. It is important that supervisors initiate this process in order to model how the supervisee might do likewise.

– Supervisors can help supervisees to explore what personal experience they bring to their work, whether they feel able to use this experience in their work and how they might do so (see Table 1). This might include developing their own biography to be included in team materials.

– The process of supervision should be used to reflect on, and learn from, the sharing of personal experience, making it clear that none of us get it right first time and all of us are learning. It is vital that the supervisor gives examples of this from their own experience.

– In interviews candidates are asked to reflect on some aspect of their personal life experience and how this might enhance their practice.

– Supervision provides a context to reflect on relevant policies and procedures that relate to ‘boundaries’ in relationships (e.g. giving and receiving of gifts and ‘professional/patient’ relationships).

• Ensure that all employees have the opportunity to work to their full potential. A culture that values personal experience must also be one that BOTH enables people to talk about difficulties they are facing and supports them through these as far as is possible AND supports them to draw on the full range of personal experiences in their work. This might usefully include:

– Enabling each employee to use some of their personal experience and expertise as part of their work (e.g. someone who is keen on football organising a football team or helping anyone who wants to access local football opportunities). Work is more satisfying if you are able to do things that you like and are good at.

– Recognising that people have a lot going on in their lives and that if accommodations can be made in the work environment then well-being and performance are improved. This should include not only the ‘reasonable adjustments’ for disabled people required by the Equality Act, but also adjustments for people who may have child-care responsibilities, an appointment with a debt advisor or run/attend a yoga class.

In addition, team leaders might consider the use of ‘Team Recovery Implemetation Plans’ (Repper and Perkins, 2013). These encourage front line staff, people using services and those who are important them, to identify the full range of talents that exist within the team and share intelligence about community opportunities in order to develop plans to enhance recovery-focused practice within the team.

Training and development also have a key role to play in developing skills and understanding to enable staff to use their personal experiences safety, appropriately and effectively in their practice.

• All professional training courses should help trainees to think about what personal experience they bring, why this might be useful and what, how, when and where to share this information. Provider organisations can encourage the professional institutions from which they draw their staff to address these issues. Education providers are well placed to initiate research in this area and to consider the philosophical and ethical issues involved.

• Education departments within provider organisations need to establish inservice training courses and workshops to ensure that existing staff are equipped to confidently use their relevant personal experience in their work and training for team leaders in how to foster a culture that values such experience within their teams.

• Induction programmes provide an opportunity to convey a culture that values personal experience among new recruits. At the same time as introducing recruits to policies on ‘boundaries’ they also need to encourage recruits to value the full range of their experience and use this appropriately in their work. Introductions from Chief Executives and other senior leaders on such programmes can usefully model and encourage this.

• Individual teams and services can explore the range of personal skills, expertise and experience within their teams and reflective practice sessions about how these can be valued and used.

Conclusion

Everyone working in mental health services brings not only their professional training and experience but also a wealth of personal experience (life experiences, skills and interests outside work; culture and community knowledge; past struggles, difficulties and challenges – including mental health challenges). At present, exhortations to ‘be professional’ means that many feel that they must leave half of their experience at the door. This reduces the authenticity and humanity of relationships at work and much valuable experience and expertise is lost to those using services.

Recovery is about people growing within and beyond what has happened and discovering lives they find meaningful, valued and satisfying life. Our professional skills have only limited value in assisting people to do this, but when complemented by our collective wealth of personal experience we are in a far better place to support people to explore and realise their possibilities.

References

Audet, C. T., & Everall, R. D. (2010). Therapist self-disclosure and the therapeutic relationship: A phenomenological study from the client perspective. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 38(3), 327–342.

Bradstreet, S. (2006) Harnessing the ‘lived experience’. Formalising peer support approaches to promote recovery. Mental Health Review, 11, 2-6.

Davidson, L., Bellamy, C., Guy, K. & Miller, R. (2012) Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11, 123- 128.

Deegan, P.E. (1988) Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 11(4), 11-19.

Dorset Wellbeing and Recovery Partnership (2013) Valuing the Lived Experience of Staff Working within Dorset Health Care. Dorchester: Dorset Mental Health Forum http:// www.dorsetmentalhealthforum.org. uk/ pdfs/other/hidden-talents.pdf.

Dunlop, B.J., Woods, B., O’Connell, A., Lovell, J., Rawcliffe-Foo, S. & Hinsby, K. (2021) Sharing Lived Experiences Framework (SLEF): a framework for mental health practitioners when making disclosure decisions. Journal of Social Work Practice https://doi.org/10.1080/0 2650533.2021.1922367.

Gilburt, H., Rose, D. & Slade, M. (2008) The importance of relationships in mental health care: A qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Services Research, 8:92, http://www. biomedcentral.com/1472- 6963/8/92.

Health Education England (2020) The Competence Framework for Mental Health Peer Support Workers. Part 2: Full listing of the competences. London: Health Education England.

Henretty, J. R., & Levitt, H. M. (2010).The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: A qualitative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(1), 63–77.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLoS Med 7(7): e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal. pmed.1000316.

Lewis, A., King, T., Herbert, L. & Repper, J. (2017) Co-production – Sharing Our Experiences, Reflecting On Our Learning. Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (ImROC) Briefing Paper, Nottingham: ImROC.

Lovell, J., O’Connell, A., & Webber, M. (2020). Sharing Lived Experience in Mental Health Services. In L. B. Joubert, & M. Webber. (Eds), The Routledge Handbook of Social Work Practice Research (pp. 368–381). London: Routledge.

Meddings, S., Morgan, P., & Roberts, G. (2019). All mental health professionals using lived experience. In E. Watson & S. Meddings (Eds.), Peer Support in Mental Health, Chapter 9. London: Macmillan.

Morgan, P. & Lawson, J. (2015) Developing guidelines for sharing lived experience of staff in health and social care. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 19(2), 78-86.

Perkins, R. (2021) Valuing and Using Personal Experience in IPS Practice. London: IPS Grow.

Price-Robertson, Rhys & Obradovic, Angela & Morgan, Brad. (2016). Relational recovery: Beyond individualism in the recovery approach. Advances in Mental Health. 15. 10.1080/18387357.2016.1243014.

Repper, J., Aldridge, B., Gilfoyle, S., Gillard, S., Perkins, R. & Rennison, J. (2013a) Peer Support Workers: Theory and Practice. Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (ImROC) Briefing Paper, Nottingham: ImROC.

Repper, J., Aldridge, B., Gilfoyle, S., Gillard, S., Perkins, R. & Rennison, J. (2013b) Peer Support Workers: A Practical Guide to Implementation. Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change (ImROC) Briefing Paper, Nottingham: ImROC.

Repper, J. & Perkins, R. (2013) The Team Recovery Implementation Plan: A framework for creating recovery-focused services. Briefing Paper. Nottingham: ImROC.

Ruddle, A. & Dilks, S. (2015) Opening Up to Disclosure. The Psychologist, 28(6), 458-461.

Scior, K. (2017, November 3). Honest, open, proud. The British Psychological Society Blog. https:// www.bps.org.uk/blogs/drkatrina- scior/honest-open-proud.

Watson, E. & Meddings, S. (2019) Peer Support in Mental Health. London: MacMillan International Higher Education.

Wyder, M., Bland, R. & Compton, D. (2013) Personal recovery and involuntary mental health admissions: The importance of control, relationships and hope, Health, 5(3), 574-581.